The Federal Trade Commission has announced a settlement in its first crowdfunding case, which targeted Erik Chevalier, who created the Kickstarter project for The Doom that Came to Atlantic City back in 2012. The settlement enjoins Chevalier from doing it again, and creates a judgment for $111,793.71, which will be suspended and never be collected unless it’s discovered that Chevalier misrepresented his penury in the financial statement he provided the court earlier this year.

Chevalier “neither admits nor denies” the allegations in the Complaint filed the same day, although he agreed that the facts in the Complaint “will be taken as true” if there is subsequent enforcement litigation with the FTC.

Chevalier is enjoined from using the customer information, except to provide it to the FTC for possible refunds if there were any money collected in the future, or from keeping it beyond any instructions from the FTC to destroy it.

Chevalier is required to report to the FTC any involvement in crowdfunding activities for the next 18 years.

The case started in July of 2013, when Chevalier announced that he would not be producing The Doom that Came to Atlantic City (see “Kickstarter 'Doom'”). At the time, he blamed “ego conflicts, legal issues and technical complications,” among other issues, but also revealed that he used the money to start a board game company, relocating to Portland in the process. The Kickstarter had been presented as funding the game, not starting a company.

In fact, expenses that Chevalier said he’d incurred to develop the game, including “hiring artists to do things like rule book design and art,” were actually fictitious, according to the FTC complaint, which said, “In reality, Defendant never hired artists for the board game and instead used the consumers’ funds for miscellaneous personal equipment, rent for a personal residence, and licenses for a separate project.”

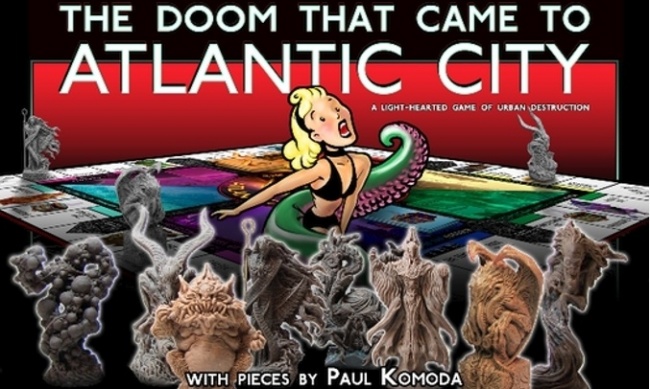

Cryptozoic Entertainment stepped in to work with the game’s creators, who were upset with Chevalier’s actions and concerned about the impact on their reputations, to take over production of the game (see “Cryptozoic Saves ‘Doom’”). The production files were lost in the transition and had to be recreated by Lee Moyer, one of the game’s creators. Cryptozoic was able to track down the sculpts and molds for the miniatures in a Chinese factory with the help of Z-Man Games founder Zev Shlasinger.

Cryptozoic shipped each of around 1200 Kickstarter backers a copy of the completed game (a $75 MSRP product) at no charge. This required contributions from Cryptozoic, which paid for the production of those 1200 copies but received no revenues, and the creators, who also did not receive any revenues from the backer copies.

Backers also took a hit, as the special pewter miniatures, art prints, t-shirts, and other premiums associated with various backer levels were not produced or fulfilled. After expecting to get nothing, backers were happy to get what they could, then Cryptozoic COO Scott Gaeta told us. “I don’t remember one negative contact from any of the backers saying ‘why couldn’t we get the other stuff,’” he said. “They were disappointed, but didn’t hold us responsible at all.”The FTC focused on the misrepresentations made by Chevalier, according to a Twitter chat held Thursday afternoon by FTC attorneys Helen Wong and Peter Lamberton, who worked on the case. The failure of a Kickstarter project to deliver “by itself may not be enough,” they said. “We look at whether the project creator made misrepresentations to consumers."

The attorneys declined to say how the investigation started.

The crowdfunding platform’s responsibilities (in this case Kickstarter’s) are limited. Asked whether the platform has “any responsibility/liability to police campaigns,” the FTC attorneys responded that “crowdfunding platforms have a responsibility to act fairly and non-deceptively,” a requirement that they presumably meet by disclosing the risks of funding a project.

Although the FTC action did not recover any money or charge Chevalier with any crimes, it may serve an important deterrent benefit. The message is that crowdfunding project creators who just walk away with the money or use it for other purposes are going to draw government enforcement attention. “Many consumers enjoy the opportunity to take part in the development of a product or service through crowdfunding, and they generally know there’s some uncertainty involved in helping start something new,” FTP Director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection Jessica Rich said in a statement. “But consumers should be able to trust their money will actually be spent on the project they funded.”

Wong and Lamberton echoed those sentiments, noting that crowdfunding is an innovative way to raise money, “but we hope to deter bad actors from misusing these platforms.”

The FTC’s education arm has offered suggestions for avoiding crowdfunding frauds (e.g., “has the creator launched other projects successfully?”), and also suggested that those learning of a crowdfunding scam file a complaint with their state Attorney General or the Federal Trade Commission.

The story of the FTC action is getting wide play, and will reportedly be the subject of a segment on Good Morning America this week. While that’s not good publicity for crowdfunding, presumably the Kickstarter community is aware of the risks and how to avoid them, so concerns about fulfillment are unlikely to deter backing future projects. And the fact that there’s government enforcement action against a bad actor can also give some security; someone is paying attention.

What of the game at the center of this case? Cryptozoic COO Scott Gaeta, who helped put together the rescue, acquired the rights to the game when he left Cryptozoic to form Renegade Games last fall (see “Crypto Vet Forms Renegade Games”). He told ICv2 that of the original 5,000 copies there are only a couple of hundred copies remaining, and a reprint is planned.