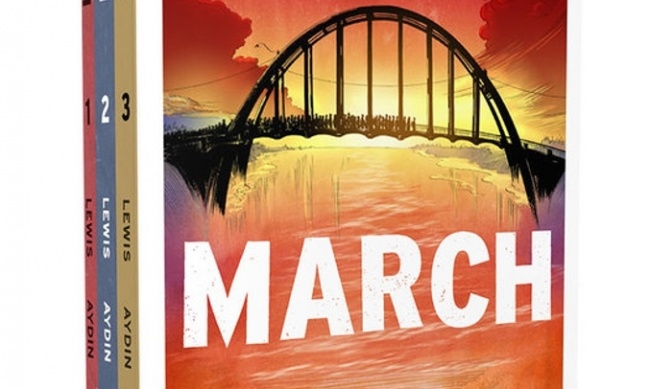

Marching toward a wider audience. March is an award-winning, best-selling graphic novel series that recounts one of the most consequential lives of the 20th century. Everything about it, including Lewis’s choice to tell his story in comics, is important.

As a young man in the segregated South, Lewis confronted barbaric prejudice with grace, courage and an unflinching devotion to nonviolence. Aydin and Powell use the storytelling power of comics to make Lewis’s struggle real to a new generation of Americans, showing the power of moral purpose in overturning injustice.

It’s an intriguing choice to adapt a work like this in animation rather than live action. Lewis’s story isn’t the stuff of science fiction and fantasy; it’s part of the actual history of this country. It’s an obvious subject for the kind of films studios produce when they want credit for social conscience, and many of the roles, from the young Lewis to the supporting cast of activists and politicians, are Oscar-bait for every serious actor of color in Hollywood. Doing an animated series doesn’t preclude doing a live action version, but it’s unusual that they’d go this way first.

Why is that decision unusual? Part of it has to do with the role that animation plays in the media world.

Cartoons for grown-ups? Over the past 20 years, we’ve seen comics “grow up” in terms of public perception, such that serious works of graphic literature generally receive critical attention commensurate with their content rather than the novelty of being – “oh my gosh, Zap! Bam! Pow! Not a comic for kids!”

Animation, on the other hand, really hasn’t broken out of the perception of being for kids, at least in the U.S. The Pixar-Dreamworks-Disney axis dominates the box office with the tried-and-true formula of “great looking animation for kids that also has adult watchability.” This also describes a lot of contemporary television fare, from Adventure Time to Gravity Falls to Star Wars: Rebels.

Nearly all the successful animated shows aimed at older audiences, from South Park to Family Guy to Archer and The Venture Bros, get a lot of mileage from the ironic distance between the perception of animation as a kid-oriented format and the actual subject matter. The Simpsons is sui generis, so let’s set that aside. That leaves the direct-to-video animated features from DC and Marvel clearly aimed at older viewers, as well as sophisticated serialized animated shows like Young Justice and Wolverine and the X-Men. But superheroes, as usual, occupy a halfway space.

The bottom line is that when you look for domestically-produced animation that wants adults to take it seriously on its own terms, there isn’t a whole lot to choose from on either the big screen on small. Forty years after the heyday of Ralph Bakshi, American audiences are still waiting for the Animated Graphic Novel to go mainstream.

Extending the medium. There’s no reason why this should be so. Doing great animation is still a big lift, but it’s not as big as it used to be. Filmmakers who have a creative approach to adapting serious work as animation now have more and better choices of tools at lower cost. For example, the software that Studio Ghibli used to create masterpieces like Princess Mononoke and Howl’s Moving Castle is now available free online.

In terms of material, many of the modern masterpieces of graphic literature depend on the properties of comics that wouldn’t translate to live action but would extend the potential of animation if they were ever properly adapted. I’m thinking specifically of works like David Mazzuccelli’s Asterios Polyp or Eddie Campbell’s The Fate of the Artist, which both use shifting art styles as a narrative device, but also of stuff like Love and Rockets, where the artistic hand of Los Bros Hernandez shapes perceptions of the characters and action.

In cases where we’ve seen this done, like the French-produced adaptation of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis from 2007, the results have been both artistically and commercially satisfying. The closest American films have come to fusing the artist’s specific aesthetic with cinema were Frank Miller’s heavily-treated live action stuff from the past decade: Sin City, 300 and (sorry) The Spirit. The fact that that technique produced diminishing returns has more to do with the subject matter and the limited vision of the filmmakers than basic concept. Surely there’s more and far better work that could be done if studios could think more ambitiously about the commercial potential of animated storytelling.

New media, new audiences. The March isn’t a graphic novel that plays tricks with the comics medium to tell its story. Indeed Nate Powell is about as pure an exponent of the straightforward Will Eisner approach as it’s possible to find in comics today. His style works effortlessly with the text to enhance readability and open the story up to readers without calling attention to technique – and I’m sure that’s by design. Lewis has said he chose the graphic novel format intentionally, as a way to reach a wider and younger audience through a more approachable medium.

The choice to do The March in animated format suggests the same thinking. It should further be noted that Ci2, the studio that optioned the property, is not a traditional animation production house; it’s essentially a high-tech collective with an emphasis on new dynamic media like augmented reality and virtual reality.

I hope the series gets produced and is successful, and not just because Lewis’s story needs to be carried forward. Animation needs a future as bright, diverse and serious as comics. Maybe this story can help pave the way.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.