Two Twitter threads over the past few days helpfully illuminate the pickle that Marvel finds itself in with respect to the direct market and the readership it serves.

In one that took place on Sunday, Marvel Chief Creative Officer Joe Quesada responded to a conversation about the possibilities of expanding the market with an ode to the remarkable qualities of the hardcore fans who "run our business," relative to casual fans "who pop in once in a while to see what’s new or if the latest TPB or OGN has shipped." It’s pretty clear where he places his bets.

In another, comic store veteran Nick Rowe detailed Marvel’s precise tactics for maximizing revenues from reboots, press-hyped events, variants and other collector-catnip, observing that these hardball approaches to milking fans and retailers for the last dollar are what’s hurting the company’s bottom line, not the more talked-about issues of changing up established characters in the name of diversity.

The threads both reveal the extent to which Marvel depends not just on the direct market, but on the most extreme pathologies of the direct market, even as the rest of the industry looks at ways to expand the audience, widen the channel, and capitalize on the growth taking place on the trade book side of the business.

Follow the money. From Marvel’s perspective, their strategy makes perfect sense. Hardcore fans are real. They show up every week. They are not just receptive, but avid for the next thing Marvel wants to sell them. Quesada is correct to observe that few if any other consumers groups exhibit this kind of behavior. Failing to exploit them to the fullest is just leaving money on the table for competitors.

Casual fans, by contrast, are great in theory, but they cost more to acquire, and they don’t provide the steady revenue stream that longtime Marvel Zombies do. While it would be unwise to neglect them completely, why invest resources on a market with an uncertain rate of return?

This is almost certainly unhealthy in the long and medium term, but Marvel executives are not paid to care about retailers, the industry as a whole, or the long term. Their job is to make what money they can from the situation as it is. In a quarter-to-quarter business, maximizing dollars from a captive market of hardcore fans and the retailers who depend on them is a lower-risk strategy than chasing the mirage of new readers who may never provide the kind of lifetime return on investment as the base.

There is one and only one way out of this zero-sum trap: figure out a way to reliably convert casual fans into habitual readers. This might sound trite, as well as nearly impossible to do, since the interests and obsessions of hardcore fans diverge so dramatically from those of newbies. But it can be done, because it has been done.

Marvel needs a gateway drug. Let’s examine the first and best case of this happening in the Direct Market era. Think back to the late 1970s and early 1980s when the majority of today’s post-Silver Age fans went from buying a handful of comics at the newsstand to becoming Wednesday Warriors. What drove them to it?

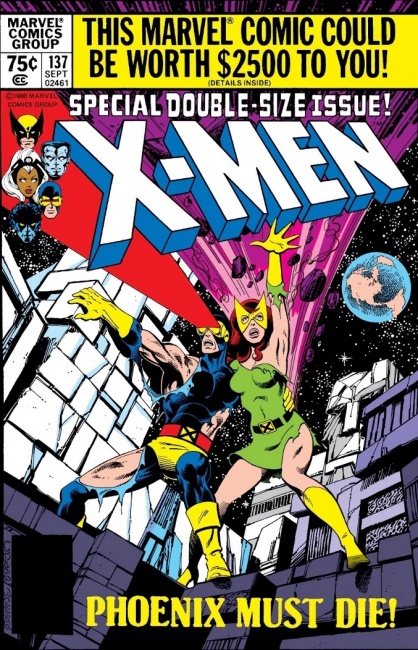

The X-Men. Specifically, the X-Men written by Chris Claremont and drawn by a cavalcade of talented collaborators extending from Dave Cockrum and John Byrne to Arthur Adams and Jim Lee. Almost every Marvel and superhero fan from that now-aging demographic that fueled the pre-crash rise of the Direct Market in the 80s and early 90s came in through the door marked "X," even if they ended up staying for unrelated popular properties like Spider-Man, Daredevil or the Punisher, or moving on to more sophisticated fare.

The freakish, dare I say uncanny success of Claremont’s X-Men is so towering in its implications for comics retail that we can barely perceive it. Issue after issue, title after relentless title, readers kept buying because they wanted to know what was going to happen and cared deeply about the outcome. Then they began expecting that experience from other books they bought. Collectability played a part, but that was fleeting relative to the genuine reader enthusiasm that created hundreds of thousands of habitual superhero comic fans.

Yes, Marvel eventually broke the camel’s back with too many titles, too-complicated storylines and too many gimmicks, but it was a camel strong enough to move the needle. In the 30 years since this phenomenon transformed the industry, many have tried to replicate it but few if any have succeeded, at least not on a long-term basis and not at scale. And it can’t be encouraging that the only contemporary creator with a credible claim to Claremont’s legacy of manufacturing new hardcore superhero fans – Brian Michael Bendis – just signed an exclusive with Marvel’s biggest competitor.

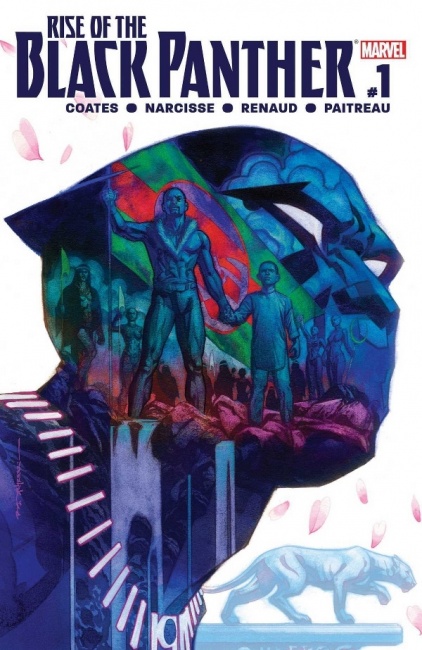

It’s not so easy to fire up the fan factory. Marvel has a few creators on its roster capable of hooking new fans with charming, quirky concepts, and it has a host of talented folks who can keep the long-timers happy with deep continuity and knowing nods to Marvel history. But it has fumbled the handoff over and over again, for reasons that come down to the fact that what Claremont did was practically unique. Even writers as talented as G. Willow Wilson and Ta-Nehisi Coates have had trouble pulling Ms. Marvel and Black Panther fans into more continuity-centric titles, though Marvel’s recent impatience with slow-starting series hasn’t helped.

The bottom line is that Marvel’s hardball tactics will continue to yield diminishing returns until they can fix this part of their pipeline. Quesada certainly understands this, and the company’s recent changes at the top, bringing in new Editor-in-Chief C.B. Cebulski and shrewd industry insider John Nee as publisher, show that they recognize the urgency of a better strategic approach.

Unfortunately, it’s not as easy as just saying "cook me up another X-Men," especially if mutants are still off the menu in Marvel cosmology. It’s also clear that today’s generation of fans lacks the acquisitive collector spirit that drives the hardest hardcore fans into pestering retailers to order variants and other gimmicks. Even if more of them become Wednesday Warriors, they won’t fall for those same tricks. If there are enough of them, though, maybe Marvel won’t need them to.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

Posted by Rob Salkowitz on January 29, 2018 @ 7:03 pm CT