ICv2: Let's talk a little bit about your graphic novel. We understand that's a collection of material originally published in Dark Horse Presents?

Paul Levitz: The story ran originally as a serial in Dark Horse Presents. It's not a collection in the sense of being a series of short stories or something that wasn't designed to be a novel. It was a novel that was published in serial form.

A mystery novel in serial form over a year and a half is a challenging structure to actually get people to read and follow. I think it's a pretty fresh experience for 99 percent of the audience. We've seen other, we'll call them "experienced" comic writers or artists do things later in their careers that tend toward the autobiographical. How did you end up writing about crime and PTSD?

[laughter]

I was taking advantage of Brooklyn, which is, if not autobiographical, at least the place I grew up. I love detective stories, mystery stories.

I learned a lot of my craft with Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Ed McBain, great masters of the field. I used a lot of their structural elements over the years in stories I wrote, but it was always in other kinds of stories. With the market where it is, I had the freedom to do something. "Oh, let me see if I can do that trick that I loved all the years." That brought me to telling a mystery story.

Brooklyn was both a tip to the, if you will, the autobiographical, to the place that I knew, even though it's a pretty different place now. Also, where I grew up is now cool. It became something that might attract people's interest.

Let's talk about the comics business; you've obviously got a great long‑term perspective on that. Do you think the recent changes in the business, the declines in periodical sales, for example, are a secular or a cyclical change?

I think there's several secular changes relative to the periodicals that are challenges. One, that with the massive availability of the graphic novel format, assuming that you want to read a good comic constantly, you can choose from the best comics that have ever been published, and a wide range of it.

When I started, certainly, if you went in to read a good comic, you had a choice of whatever this month's best comics were or maybe this week's best comics were. Very little of the classic material was available. If you had a passion to read "Batman," you had a choice of perhaps two or three things.

Now you probably have a choice of 15 different periodical Batmans, but you also have a choice of probably 50 great and wonderful Batman stories that you've heard about. That's a competitive force that is very powerful.

The other challenge is, with the success of the film and television adaptations of particularly the super hero material, you can get your story sense of the super hero stuff satisfied on a pretty constant basis without reading a print comic book. The most successful periodicals we've had for a long time have been the super hero titles. They face competition from their own other incarnation.

Both of those are strong forces.

There's also obviously the cyclical issue of strength from both of the major houses, in particular from Marvel. Marvel, since the beginning of the Direct Market, has been the most significant force bringing people in for periodicals on each Wednesday or whatever the new comics day was.

They've had a rough batch of years in terms of reader enthusiasm. Still good volumes of sales, but you can see from the online discussions, you can see from the retailer reactions, that they haven't caught fire with anything in an exciting way with their major brands in the last couple of years. That hurts the comic shops. You need at least two or three of the engines on the jet firing at the same time for the shops to be healthy.

Image has done some interesting stuff that's sustained itself, obviously The Walking Dead, Saga, Monstrous. DC seems in better shape than they were a couple of years ago, but Marvel hasn't fired up again. Hopefully with CB settling in editorially, he'll have some fresh things to say and that'll create a window of opportunity.

That's what you need to get out of the cyclical part of that problem.

Looking forward at the comics business, what's the scariest thing you see for the future of comics? What's the most promising thing that you see for the future of comics?

The most promising thing is clearly the growth in the different genres and content forms. When you look at the bandes dessinées, it's about 13, 14 percent of French trade publishing. We're still about three, four percent of American [trade publishing]. I've got to believe that a big piece of that gap is simply that they offer more flavors when you walk into the bookstore.

A few years ago, we were offering versions of one flavor, the adventure story. We're much better now, but we're still way behind where they are. Every time you get a Raina [Telgemeier] who speaks to an audience that nobody's managed to reach, that audience starts looking for more things afterwards. She's the most dramatic case, but we're seeing that happen in a lot of little spots, as well.

The scariest thing is that the model for bookselling in the graphic novel form is a very different economic model than it was in the periodical business: many fewer turns, a lot more cost of inventory carriage, different physical space needs, different outreach needs to get a wider range of customers.

We're seeing a fair number of comic shops adapt to that and thrive, but we're seeing some that are having problems making that transition, or where it just isn't emotionally rewarding enough to persuade the proprietor to do it, or a new generation of proprietors to step in.

Comic shops have always been as much an emotional business decision as a rational business decision to operate. You did it because you loved the form. You love the sports bar feeling of having people there talking about the things you cared about. Can we continue to bring in new people as operators, as owners? Can they rise to the economic challenge?

Starting a comic shop is enormously more expensive than it was 25 years ago because of the inventory you have to carry. Building a customer base to carry that must be a slower process than it was 25 years ago. I have a harder time putting numbers to that in my head, but it feels like that must be the case. That combination is scary.

The comic shops have been vital to the health of the field because of their support of what is new. When you look at the mass merchants (and I'm not simply talking about things like Walmart, but even the Amazons of the world, the Barnes & Nobles of the world), they're very passive about bringing anything new out. They may stock it. Amazon obviously will stock everything that comes out, but there is no hand‑selling. There's no bets. They don't get passionately behind new things, unless the new thing comes from a very established brand.

Comic shops are driven by passion, and they're open to what is new; not all of them, not everything, not all the time, not every comic shop. As a structure, the Direct Market has been enormously supportive of experimentation and revitalization. Whether that's supporting a brand‑new title from a Marvel or a DC by a talent nobody's ever heard of, but whose stuff looks interesting, supporting new publishers.

That injects energy into the field every time, and injects the possibility of bringing new bodies of readers in, in a way that the mass merchants aren't energetic about. If the comic shop side of the business gets weaker, our ability to keep growing in radical new ways gets weaker.

True that. You’re up for the Eisner Hall of Fame. What do you regard as your most important contribution to the medium, and we'll say, so far?

Bless you. My most important contributions to the medium were on the business side, implementing structures that became standard for the industry to give creators a better stake in their work.

That fueled a tremendous amount of the explosion of creativity in the early and mid‑80s. The work building and solidifying the Direct Market, and ultimately, the graphic novel format.

None of these were uniquely mine. None of these, even within the acts of DC, were individually all mine. The creator's stakes would never have been possible without Jenette Kahn as a partner in crime, and really, philosophical leader on many of those issues.

The hard grunt work and structural work that I did in many of these cases helped us build to the structures that we've today, and I'm very proud of that. That enabled a lot of what comics are today.

Getting us through crises like the Heroes World mess. Whether the solution was the ideal solution that you would vote for in the process or not, you're certainly as conscious as anybody else of what was at stake, and the many ways that that could have turned out even worse than it did.

I think for a long time, DC was just a very reliable partner to the other stakeholders it worked with, the creators, the distributors, the retailers; not always right, not always making the perfect or smart decision on something, but always trying to do things that was respectful of the partnerships it had in the business and trusted for that. I'm very proud of that. I don't say that, again, against anybody else's run anywhere, DC or our competition. I'm proud that we were a good place to do business, as a major player in the business, that was supportive of everything good about it.

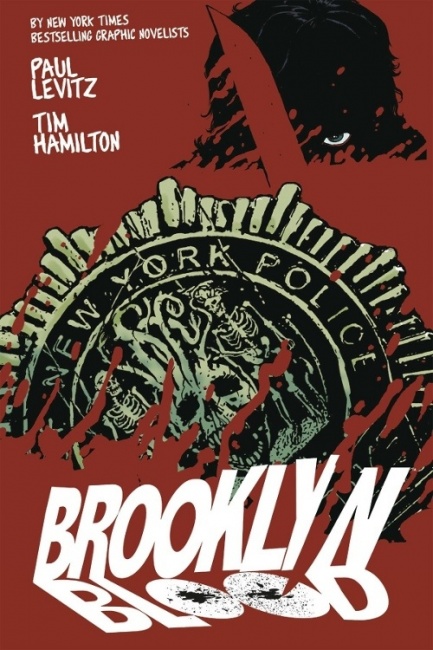

See preview (cover plus 6 interior pages) in the gallery below!

View Gallery: 7 Images

View Gallery: 7 Images