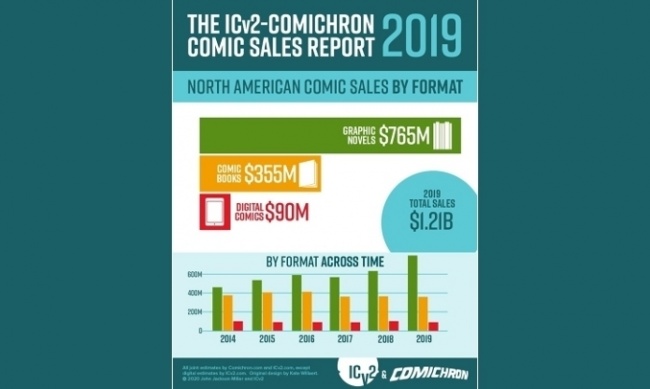

Last week ICv2 and Comichron released their annual market data on North American comics and graphic novel sales, with the bittersweet news that sales rose a booming 11% between 2018 and 2019, a performance I suspect we’ll have a hard time repeating this year. According to their analysis, a majority of the record $1.21 billion sales came from graphic novels, particularly kid-oriented titles sold through bookstores, online retailers and online (see "Comics and Graphic Novel Sales Top $1.2 Billion in 2019").

The big news from the survey confirmed earlier hints that we saw back at the ICv2 Conference at New York Comic Con in October 2019, showing not only a shift from the direct market to the trade book channel, but also a shift in format from periodicals to graphic novels. At that time, I wrote at Forbes that these dynamics portended an even bigger change to the fundamental character of the comic market in the U.S. – away from superheroes that have driven sales for decades, and toward manga and kids comics that appeal to a younger, more diverse audience.

Reaction to this piece was fairly emphatic, since the suggestion of a move away from superheroes sounds like the end of the world as we know it to a certain demographic of readers and retailers. Now that we have full 2019 numbers, we know those trends in fact showed up on the balance sheets at year end (see, on the ICv2 Pro site, "Superheroes Lag in Graphic Novel Golden Age"). What does that mean?

The Loyalty Loop collapses. First of all, this outcome was both overdetermined and a long time coming. Superheroes rose to dominance in the 60s and 70s, when comics were cheap and there was relatively less competition for kids’ attention. A new generation of creators in the 70s and 80s upleveled the storytelling in superhero comics, introducing complexities, themes and worldbuilding techniques designed to appeal to the older readers who gravitated to comic shops. Collecting old storylines for trade book distribution was relatively rare, so fans had to buy piles of issues (and back issues) to get the whole story. Add all that together and you’ve got the makings of a great business, selling relatively respectable fantasy and superhero work to a small, loyal group of readers/collectors with disposable income and deep sentimental attachment to the content.

I’m sure nearly everyone reading this knows the story inside and out, which is itself another part of the problem. The comics industry, publishers, retailers, readers and collectors, all over-learned the lessons of this era and kept repeating the same formulas over and over again in the face of massive evidence that the market was changing.

DC and Marvel wasted the better part of two decades between 2000 and 2020 failing to react to these changes strategically or incrementally. Given the choice between making an authentic play for a wider, younger audience or trotting out this year’s version of the same tired clichés, reboots and events, the Big Two constantly opted for the latter. By the time they made some cursory efforts to adjust to the changing tastes of younger readers, they’d trained two generations of fans to resist all change and reject anything that appeared to retreat from the dominant style of over-drawn, over-written, overwrought superheroics.

The trade collection well runs dry. As the market shifted decisively toward trade collections as the format of choice, publishers at first were able to monetize their huge back catalog of "classic storylines" along with current story arcs that were purpose-built for collected editions. But as the supply of quality material started to dry up, fewer new storylines measured up to "must-read" status – even less-so, because constant reboots of the story universes left a lot of material outside of current continuity, and therefore irrelevant to exactly the most dedicated, habitual readers that superhero publishers need.

We also discovered fairly early into the superhero movie and media era that success on the big screen, or the small screen, or the gaming console, didn’t translate to sales of ongoing titles, even in those rare cases where publishers tried to align the stories in the comics to the expectations of the massive media audience.

It’s simple math that if superheroes were losing fans who’d come in during the 70s, 80s and 90s and not replacing them with young blood when they aged out, the genre (at least in comics publishing) was on borrowed time. And it was especially unhelpful when diehard old-time fans chose to see every effort to appeal to the tastes and values of younger readers as some kind of political conspiracy – or, at best, a clumsy, unwelcome reminder that the world they knew was changing around them.

Moving backwards while others move forwards. What’s remarkable is how the rest of the business has changed, to the point that comics were an exciting publishing success story last decade despite the decrepit state of its core genre. Manga, for example, has grown triple digits since the 2011 market trough. And while most superhero comics have not been able to get much lift out of their billions of dollars’ worth of media air cover, the popularity and sales of manga is driven directly by the prevalence of new anime on cable and streaming services.

Then there’s the kids market. While DC and Marvel studiously neglected younger readers – for what must have seemed like good reasons back in the 2000s and 2010s – every other corner of the publishing industry seems to have gotten the memo that kids, tweens and teens love to read. Give them prose books and they will read them faster than authors can churn out sequels. Same with graphic novels. There’s no reason those graphic novels couldn’t have been superhero-based rather than original properties, except for the fact that the owners of the most popular superhero IP had no interest in either producing kid-oriented comics themselves or licensing it out.

That wasn’t just silly in the short run; it’s created a bigger problem down the line. A whole generation has grown up loving Raina and Dav and Kazu, not just the creators and the titles, but the aesthetic and atmosphere of that kind of work, which, in case you haven’t noticed, is about as far from the house look of DC and Marvel as it’s possible to be within the same medium. Those readers are now aging up into more sophisticated original graphic novels, creating a bonanza for the various imprints of Hachette, Penguin Random House and others who can now smell the money.

Barring a few curious folks who check out the DC and Marvel shelf because they liked the movies, that generation is never going to feel the same bond with superhero comics as their elders. As I wrote earlier this year, they may retain the comic-buying habits into adulthood, but they lack the "training" that past generations had in continuity, collectability and canon, and are therefore much less likely to fall for the usual tricks that publishers have used to keep those readers on the hook month after month (see "Will Today’s Young Graphic Novel Fans Stick Around to Save the Industry?"). They’ve also endured a lot of gatekeeping, condescension and abuse from self-appointed comics traditionalists, which probably doesn’t make the delights of old-school fandom seem very appealing.

The long twilight. All the factors pointing to the market decline of superhero comics is like one of those Agatha Christie mysteries where there are too many sets of prints on the murder weapon. Everyone has taken a swipe at the body and it’s still not quite dead. In fact, even though the superhero-dominated category of periodicals sold through the direct market has been eclipsed by faster-growing channels and formats, they still represent a hefty chunk of the total.

It’s also worth noting that DC and Marvel have both gotten into the young reader market in a big way, and perhaps that will be a case of "better late than never." DC has been investing in a strong young reader program since 2018, and Marvel’s recent deal with Scholastic, for example, seems like a step in the right direction. Just imagine if they’d done it in 2010.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

Posted by Rob Salkowitz on August 3, 2020 @ 6:45 pm CT