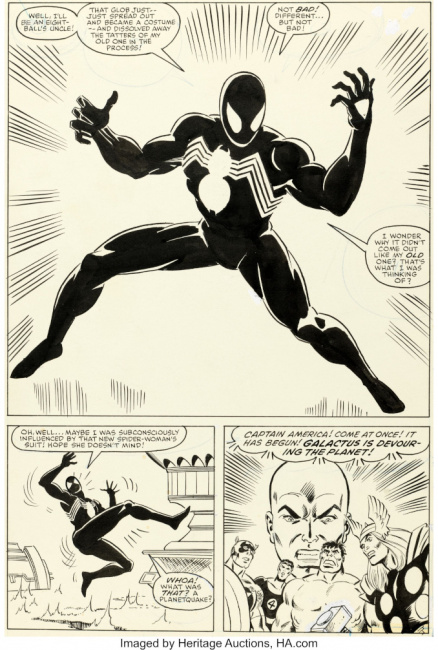

If you pay any attention at all to the art and collectibles side of the comics business, you probably saw that last week’s Heritage Auction generated some pretty astounding results, including a record $3.36 million for a Mike Zeck page from Secret Wars #8 featuring Spider-Man sporting his spiffy new black costume (see "Auction Sale Of An Original Black And White Piece Of Comic Art Breaks U.S. Record"). Altogether, $23.76 million changed hands as more than 4,900 bidders swarmed in to buy every single one of the 1,333 lots on offer.

I want to focus on the art side of this in particular because the kind of sales these pieces are realizing are not only different in degree from what we’ve seen in the original art market before, they’re different in kind.

Why that page? When I first heard the news about the sale of the Secret Wars page, I thought someone must have added an extra zero to the price by accident. After all, previous to this, the record sales we’d seen for line-art (as opposed to fully painted piece by Frank Frazetta, for example) were in the mid-six figures, with the Herb Trimpe Incredible Hulk #180 page featuring the first appearance of Wolverine fetching over $657K in 2014, and several Todd McFarlane covers also in that price range.

Here was a panel page by a well-liked but not especially notable artist, featuring an early appearance of the black costume, which went on to have some legs in the comics and the movies when it was later revealed to be the symbiot Venom. OK, fine, but it’s not the first appearance: that was technically Amazing Spider-Man #252, and it had appeared in several other books as well. And it wasn’t the cover, which is at least as iconic as the image on the page, and is, you know, a cover.

Now people want what they want, and when the bidding gets hot and heavy during an auction, prices tend to rise on exuberance and adrenaline. But man, that’s a lot of money, and it suggests there’s even more money on the table for other notable first appearances or key moments drawn by artists who are themselves collectable for other reasons. What would the first appearance of Elektra, drawn by Frank Miller and Klaus Janson, bring if it ever hit the market? Or the first appearances of the Black Panther, Silver Surfer or others, drawn by Jack Kirby and Joe Sinnott?

The mystery of the missing Marvels. One reason that many of the key character first appearances from Marvel’s Silver Age haven’t turned up is because no one, officially, knows where they are. Lots of those books were drawn by Jack Kirby, whose original art was famously held by Marvel against his wishes well into the 1980s, and when it was finally returned, the inventory listed only a tiny fraction of the pages that the King had drawn. Among the missing were many, many key issues, iconic scenes and character first appearances.

Some portion of these pages might actually be lost, as publishers, including Marvel Comics, didn’t consider original art to be anything other than an artifact of the production process. We’ve all heard the stories of art being cut up, thrown in the dumpster, reused or otherwise treated in a manner unbecoming of something that would eventually be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Some portion of the pages were likely given to creators and fans by Marvel. Even though they weren’t really Marvel’s to give away, the recipients can believe in good faith that they got them in a legitimate way, from a legitimate source.

Then there are the other pages. The ones that left Marvel offices inside the portfolios of sticky-fingered freelancers, or were pilfered by fans-turned-pros, who knew exactly what they were and what they could be worth. This systematic theft of art is well-enough known that it’s not even an "open secret", but as long as pages were changing hands relatively quietly at convention tables or private sales, no one had any incentive to raise a stink.

Now, however, with huge piles of money potentially on the table, how long will these transactions remain in the shadows? How many of these pros, at the end of their earning years, looking to fund their retirements and perhaps basking in today’s general culture of shamelessness and impunity, might finally come forward with the masterpieces that they’ve kept locked away in flat files or framed in their private studies? And how many people would be willing to spend millions on them, no questions asked?

Personally, I hope that when they do, at least some of the outrage directed at "problematic" people and situations of the past can be brought to bear on folks who, at best, told themselves they were only stealing from their employer, but in fact, stole from their fellow creators and their families. They may be beyond the reach of the law at this point, but they’re not beyond the reach of accountability if and when they cash in. That includes dealers who trafficked in this stuff knowing exactly where it came from.

Heritage, for its part, had this to say about provenance: "We work with our consignors to ascertain the provenance of all of the properties that we sell, across all categories. With internationally advertised sales and industry-leading expertise across more than 40 categories, it is infrequent that properties of suspect or dubious origin would even be offered to us for consignment. Importantly, as part of the consignment process, our consignors represent and warrant their right to sell the property that they consign. While issues of title do arise from time to time, they are infrequent, and we are eager to help facilitate their resolution."

Does that make you feel better?

Impact on exhibitions. Another biproduct of the raging hot market, brought to my attention by an industry professional who prefers to remain anonymous, is how this will affect the growing popularity of comic art in museums and travelling exhibits. It’s already hard enough for institutions to pry masterpieces out of the hands of private collectors to put on temporary exhibit, much less afford to build a permanent collection.

But with prices today 5-8x what they were even a couple years ago, there’s also the matter of insurance. It’s one thing to insure a show with $2 million worth of art on display. It’s another to insure $20-50 million. If comic art is harder and more expensive to display, it could cool the momentum in the museum space for these shows, and consequently diminish the hard-fought cachet that comic art is just starting to establish in the culture.

Where’s all the money coming from? One last item that bears mention is the root cause of all this asset inflation in the art and collectibles market. Obviously the people who have seven figures to spend on old comics and original art are doing pretty well. If they’ve been in the stock market the last decade or so, they’ve probably doubled their money, with a lot of those gains coming in the last few years.

On the other hand, if you bought Bitcoin or Ethereum in the mid-2010s, you probably made 25-1000x on your investment, depending on when you got in and whether you held on. Even with recent turbulence, Bitcoin is trading over $40K right now, which means that Secret Wars page would set you back about 80 BTC.

It gets better (or worse). Last year, NFTs went from basically zero to a $40 billion market. Now I know we all have Important Opinions about NFTs, but whatever you think about the industry or the people in it, the fact is that $40 billion was just created out of nearly nothing, and most of those buying and selling are collectors of one kind or another. In NFT-land, you could buy that Secret Wars page for the prices realized from the two most expensive Bored Ape Yacht Club tokens, plus a little pocket change.

Bottom line: even an overheated market looks pretty reasonable when you’re playing with the house’s money, and the house is flush. More to come, I’m sure.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

Posted by Rob Salkowitz on January 18, 2022 @ 2:18 am CT