When DC Comics introduced the concept of Earth-2 back in 1961, the company probably didn’t quite realize what a fracture in the space-time continuum it unleashed. Back then, the notion of parallel dimensions with their own pantheons of superheroes, who once in a while got to meet each other, was fresh and novel. But like so many things in the Peak Geek era that our younger selves couldn’t possibly imagine would be embraced by the world at large, the multiverse concept is having a moment at the center of so, so much entertainment – one which may get much bigger very soon.

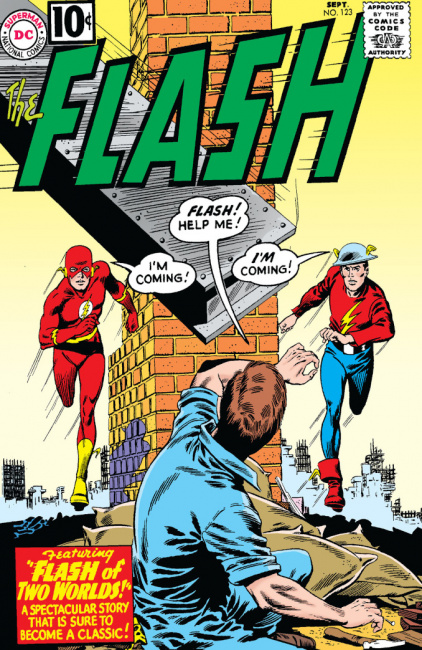

Working out on the cosmic treadmill. The original multiverse concept was reportedly the way that editor Julius Schwartz and writer Gardner Fox, both old-school science fiction folks, responded to the pesky letters from fans like Jerry Bails, who remembered DC’s Golden Age heroes, including ones with current-day namesakes like The Flash, and lobbied for them to be reintroduced to DC. In short, it was fan service.

It was also the springboard to some of the more memorable stories of DC’s Silver Age, standouts during a period when the company was getting caught by, and then passed by, the more imaginative Marvel. Like many fans of a certain age, I lived for the summer crossovers when the Justice League would meet their Earth-2 counterparts for a multi-issue team up, often involving the discovery of yet another Earth full of costumed crusaders that DC had acquired off the remainder table.

At its best, the conceit of multiple universes made readers feel like they were part of some massively large story tapestry, while serving the market function of marshalling whatever enthusiasm may have been left for the reintroduced characters, giving them a running start into their own series. But eventually, the overhead of maintaining so many different Earths and pantheons was deemed too confusing for new readers and was scrapped, at least temporarily, by 1985’s Crisis on Infinite Earths.

Into the Verse-a-verse. Let that sink in. A concept that the Powers That Be considered too convoluted and geeky for mid-80s era comic book readers is now the driving force behind some of 2022’s biggest movies.

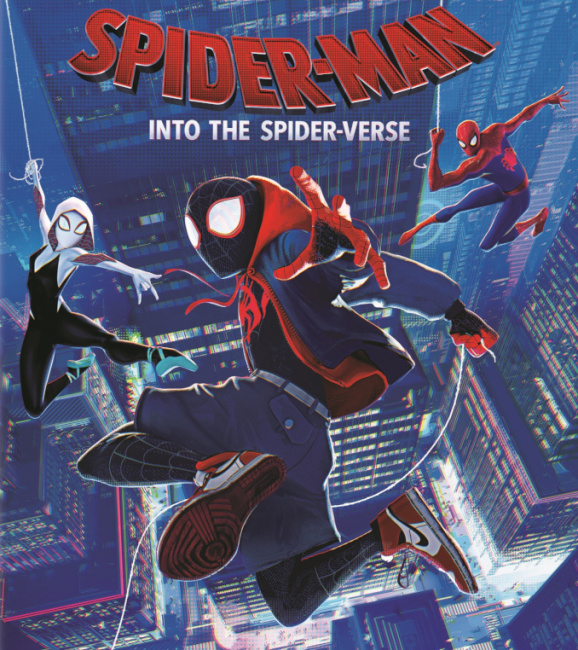

How big? Well, Sony got the ball rolling with 2018’s animated Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, itself a partial retelling of a concept first introduced in the mid-1990s animated Spider-Man series produced by John Semper. By the time the film came out, Marvel had already established a couple of separate timelines populated by different Spideys, so this was a way to bring different versions of the character, including Miles Morales and Spider-Gwen, to the screen.

Around the same time, DC’s cluster of Arrowverse shows got in on the action, taking 2019’s crossover interdimensional with an ambitious, and surprisingly successful, adaptation of Crisis on Infinite Earths itself. In that 4-part series, characters from the Arrowverse not only hobnobbed with the title characters from other shows, but with just about every media version of a DC character, including 1960s-era Robin Burt Ward!

In terms of fan service, this was a cabinet of unexpected curiosities, a veritable five-layer wedding cake flocked with frosting and ornaments. OMG, is that Lucifer, from the show that runs on a totally different network? And Kevin Conroy, the booming voice of animated Batman, in the Kingdom Come Batman exoskeleton? And… a cameo from Ezra Miller, the Flash from DC’s never-to-be-crossed-over-with-TV movie universe?

Marvel, being Marvel, was not to be outdone, pulling out many of the stops with Spider-Man: No Way Home and apparently pulling them all out in the forthcoming Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness. Expect the Flashpoint movie to follow suit.

Breaking the fifth wall. It used to be that breaking the fourth wall – the one separating actors from the audience – was a theatrical special effect only to be used sparingly. These days, of course, it is just an ante at the table for any self-respecting ironic storytelling. But the fifth wall is the tough one. That’s the wall that separates properties owned by different media companies, or that exist within impervious silos within the same company.

We’ve seen this before, in mashups like Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Space Jam and the ongoing Lego movies. Those are fun, but they’re not the serious business known as canon.

Marvel, on the other hand, looks like it is about to bring this practice right into the center of its multi-billion dollar franchise conveyor belt. Part of this is driven by backroom deals: for example, reuniting the wayward X-Men and Fantastic Four properties with the MCU. All that took was $71.3 billion to acquire 20th Century Fox. Wrestling the Marvel streaming shows of the mid-teens away from Netflix was probably child’s play by comparison, but either way, it seems to have happened.

Since all these properties come trailing their own canonical storylines, the easiest way to reconcile them within the MCU master plot is through the multiverse mechanism. It’s that possibility that has fans running detailed audio analysis on the Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness preview trailer to figure out if that’s actually Patrick Stewart’s voice that we hear for like half a second. I mean, yes, it would be complicated to shoehorn a dozen X-Men movies into the MCU through whatever storytelling trickery the writers might consider. On the other hand, it would be hard to make less sense than the existing X-Men movie timeline anyway, so why not?

Meanwhile, back on earth-comics… The multiplicity of multiverses in the media world is a relatively new development, but in comics, it’s old news to the point of being almost a punchline in a witty series like Ahoy’s The Wrong Earth.

Comics have moved on to new vistas of crossovers, bringing licensed characters with different owners together in a single story universe, as Marvel has been doing with Conan, for example. These aren’t one-off crossover events; they actually appear to be part of a broader integration of characters into existing continuity.

It's likely that the media giants are using comics, as usual, as a test strip for experiments that will eventually get loose in the wider world. Everyone reading this knows what Disney owns besides Marvel, for example.

Like the very first "Crisis on Earth 2" story more than 60 years ago, any such crossover would be fan service clad in the flimsiest story concept. But there are a lot of fans needing a lot of service, and with enough universes, almost anything is possible.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

Posted by Rob Salkowitz on March 8, 2022 @ 2:39 am CT