Confessions of a Comic Book Guy is a weekly column by Steve Bennett of Super-Fly Comics and Games in Yellow Springs, Ohio. This week, Bennett tells us the story of the world’s most dangerous comic.

When it comes to comics I'm not that picky. I'll read just about anything in comic book form that happens to be handy, especially if it's free. But if I had to name a kind of comic that I couldn't see myself reading on a bet it would have to be comic book biographies, as opposed to biographical comics. The difference being biographical comics is suggestive of works of a serious literary intent like Maus and when I think of comic book biographies I tend to think of, well, merchandise; things that are either cheesy puff piece promotional items or propaganda. Anything from Christian Spire's Tom Landry and the Dallas Cowboys to whatever the latest celebrity bio from Bluewater is, which is, hey, they're doing a Charlie Sheen bio titled Infamous: Charlie Sheen. Now that's a surprise.

Considering how often it happens it's a good thing I enjoy being proven wrong.

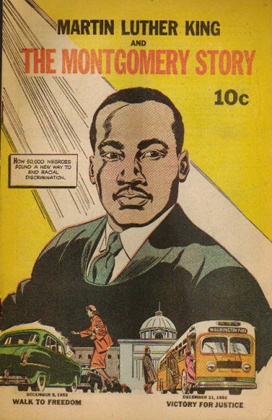

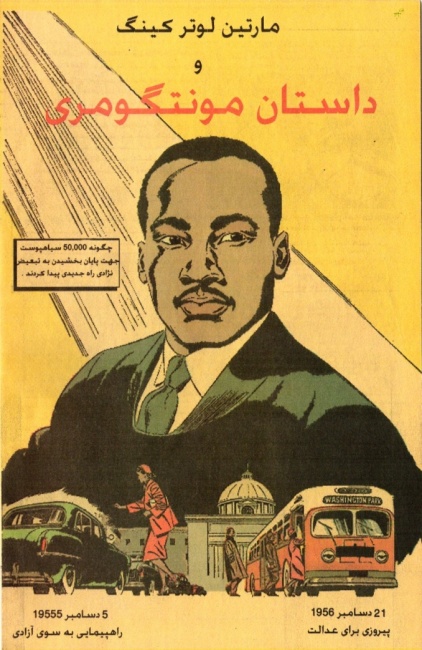

I'm not sure where I first read how copies of the comic book Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story translated into Arabic and Farsi by activist Dalia Ziada supposedly helped inspire the recent Egyptian protests that brought down Hosni Mubarak, but most likely it was at ICv2 (see "Comic Inspired Egyptian Protests?"). I wanted to believe it, but it also seemed too good to be true. I also wanted to know more, but then I got distracted by something shiny and proceeded to forget all about it. Until yesterday when I came across a story by Michael Cavina on the online version of The Washington Post titled "Amid revolution, Arab cartoons are drawing attention" about the importance of cartoons in the Arab world. But in it there was also this:

Since first publishing the book in 2008, Zaida and her group, the American Islamic Congress, say they have distributed thousands of Arabic-language issues of Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story in the Middle East, including in Tahrir Square at the height of January's revolution... "The book is an inspiration to all young people, and it helped so many understand the core strategy of the American civil rights movement and compare it to other nonviolent movements in India and South Africa," says Zaida.

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story was a 16-page comic book dated December 1957 published by the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the name used by a number of nonviolent religious organizations. According to the indispensable Grand Comic Book Database it was written by Benton Resnick (I've found several references online to Resnick being a 'blacklisted comic book writer' but have been unable to find any other information about him), an editor and writer for Al Capp's Toby Press (Capp of course was the creator of the comic strip Li'l Abner) and drawn by the "Al Capp Organization."*

The comic told the story of Dr. King and the Montgomery bus boycott and offered instruction on how to use passive non-violent resistance. 250,000 copies of it were printed and distributed through churches, universities, social justice organizations and labor unions and became a guide to the Greensboro Four, the black students who sat Woolworth's drugstore counter in Greensboro, North Carolina that was reserved for whites only.

At the SeattlePI website I found this quote from Joe Wos, founder and director of Pittsburgh's ToonSeum about how dangerous it was to posses a copy of the comic in the South: "People were told to read it, memorize it, and destroy it because if they were caught with, they could be killed."

Very few copies of the comic have managed to survive (though there is one in the Smithsonian) but if you're interested in reading it shouldn't take more than few seconds of Googling (or if you prefer Binging) to find a copy of it online in both English or Spanish. And I hope that you do because it's a comic that even fifty years later is still worth reading. Of course it's Martin Luther King's ideas, not the format in which hey appear in that matter, but I can't help but feel a certain amount of pleasure having indisputable facts at my disposal demonstrating that comics really can be important, evidence of what comics can do and be and an example of what they can and should aspire to. Knowing this won't help anyone sell more copies of Fear Itself, but it's still nice knowing.

* Though in a piece published by the Huffington Post by Barbara Beck on January 18th titled "Near Forgotten MLK Comic Gains in the Middle East" claims that it was drawn by the late Dan Barry, best known for his work on the comic strip Flash Gordon but I haven't been able to substantiate that. If anyone out there can confirm this, please let me know.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Column by Steve Bennett

Posted by Steve Bennett on March 8, 2011 @ 11:26 pm CT

MORE COMICS

'Hama Files Editions' Will Include a Letter from the Creator

August 11, 2025

Each issue of the Hama Files Editions will include a letter from Hama with background information about the comic.

From Marvel Comics

August 11, 2025

Spinning out of Deniz Camp and Juan Frigeri's Ultimates,Ultimate Hawkeye #1 by Taboo, B. Earl and Michael Sta. Maria hits stands next month.

MORE COLUMNS

Column by Scott Thorne

August 11, 2025

This week, columnist Scott Thorne notes a new twist in the Diamond Comic Distributors saga and shares his thoughts on the Gen Con releases that will make the biggest impacts.

Column by Jeffrey Dohm-Sanchez

August 7, 2025

ICv2 Managing Editor Jeffrey Dohm-Sanchez lays out the hotness of Gen Con 2025.