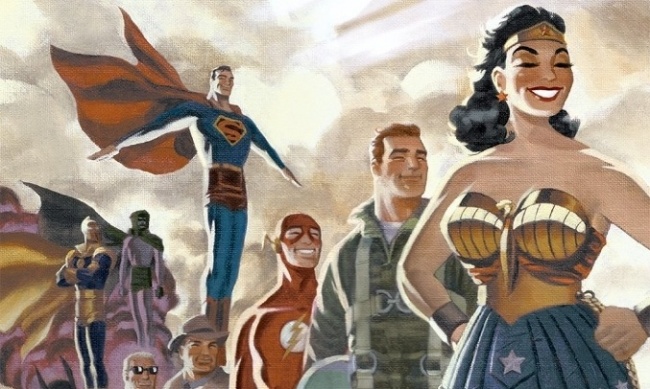

The New Frontier tells the story of the emergence of the Justice League from the primordial stew of costumed adventurers, vigilantes, detectives and daredevils that had grown to critical mass in the late 1950s. In just six issues, it ties together a couple of fun ideas from the company’s history into a complete, satisfying story. It sketches out characterizations, origin stories, conflicts and plot dynamics so clearly that even someone who had never picked up a comic book in their lives would immediately grasp not just the intricacies of the plot, but just about everything that made DC great.

The characters – and there are dozens – come off as simultaneously real and iconic. They are recognizably adult, rational, motivated individuals, but the characterizations and realism do not depend on the world of the story being dark or exceptionally violent.

Conflicts in the worldviews of Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman that define the contemporary mindset of the DCU emerged and were reconciled organically within the story, without resorting to contrivances. The ending felt satisfying but could also have easily served as the starting point for a whole universe of new stories.

In my view, The New Frontier’s greatest achievement is evoking the perceptions of innocence surrounding the early 1960s without wallowing in nostalgia or media clichés. Much as Mad Men did a few years later, The New Frontier uses the style and mindset of the 60s to help us see our own era more clearly. We lost “innocence” but gained sophistication in our awareness of social, political and environmental issues. We developed technologically, but did we advance?

It was a period piece, but one with a purpose.

Animated adaptation. The New Frontier was adapted as an animated feature in 2008. Cooke, who started his career in animation, provided the perfect template for Bruce Timm and company with his clear graphic storytelling and Dave Stewart’s flat, vivid color palette.

Notably, the story’s plot, atmosphere and complex thematic concerns survived the transition from comics to animation – a format associated, for better or worse, with being “for kids” – completely intact. The animated film ran 75 minutes and didn’t feel rushed or incomplete. In fact, it may be the best thing that DC Animation ever did, which is saying quite a bit.

When I asked Cooke once if he was satisfied with the adaptation, he beamed widely and said, “My God, how could it possibly have been any better?”

Could The New Frontier have made a convincing live action feature in the right hands? Could it have found an audience, or had its concerns updated to the present day without losing its tone and richness? Considering the creative sensibility that governs DC’s current cinema strategy, I doubt we will ever find out.

Darwyn’s Gift. In 2004, Cooke provided DC with a template for how to address its brand-defining Silver Age legacy without seeming corny or outdated. He showed how the DC pantheon could be rendered out simply for new audiences without losing its underlying richness and complexity.

He built a beautiful, distinctive and contemporary “house style” that added Kirby-esque dynamism to the clean-line foundations of Carmine Infantino, Alex Toth, and Gil Kane, while also recalling Bruce Timm’s well-loved animation work from the 1990s. Darwyn Cooke’s art in The New Frontier (and everywhere else) was a pointed rejoinder to the clotted, over-rendered work that characterizes most of today’s superhero books, carrying a whopping storytelling payload within its spare, perfectly-chosen lines.

His story proved itself adaptable to other media, and a coherent framework for integrating the entirety of DC’s story universe. If the company had been looking for a reset button to bring in new fans without driving old ones away in disgust, The New Frontier could have been a useful starting point. Today it’s a curiosity.

A Visionary Nostalgist, Still Ahead of His Time. At the 1960 Democratic convention that nominated John F. Kennedy – the man who coined the term “New Frontier” in the first place – Senator Eugene McCarthy rose in support of Adlai Stevenson, who had lost the two previous presidential campaigns to Dwight Eisenhower. At a time when the party was moving on, McCarthy reminded the delegates of a man who “fought gallantly, courageously and honorably,” who made us remember what was great about ourselves, whose attempts to speak simply to the people were rejected precisely for their simplicity and clarity.

“Do not leave this prophet without honor in his own party,” said McCarthy. It wasn’t a eulogy, but it could have been.

The party, in its way, heeded his call, even though it went on to confirm JFK as the candidate. The message that year was a clear and sophisticated updating of everything that people expected from the Democrats dating back to the New Deal. They recognized that, at a moment when competition is fierce, your brand is tarnished and the world seems to be going a different direction, there are worse strategies than to restate your ideals with vigor and hope, not fear and confusion.

When a visionary gifts you with a path forward, you should take it.

RIP Darwyn Cooke, 1962-2016.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.