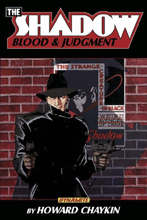

In April Dynamite Entertainment is publishing a new collected edition of Howard Chaykin’s 1980s miniseries The Shadow: Blood & Judgment, a highly influential mid-1980s series that hasn't been collected since 1991. Chaykin graciously took time from his busy schedule to discuss the project, which thanks to this new edition should reclaim its place as one of the most interesting series of the decade that gave us Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns.

What attracted you to the character of The Shadow in the first place?

Well I’m going to give you an answer that is going to annoy a lot of people. The truth of the matter is that I was only marginally familiar with the character. I had read a couple of those Belmont paperback reprints back in the earlier 1960s—I don’t know if you remember those.

I really didn’t much care about The Shadow, I’m sorry to say. I knew the character. I had seen a couple of bad movies, but the truth is it was July of 1985. I was moving to California in September and I was trying to set up and book my work schedule for the autumn of 1985 and I took on The Shadow miniseries as an assignment. That was really it.

Dick Giordano approached me at the San Diego convention that year and asked me if I would be interested. I had nothing lined up to start my work experience in Southern California, and that’s what it was. I hate to sound like I wasn’t incredibly enthused about it. I obviously brought a great deal of effort to the material. I did a lot of research once I was committed to the project, but I can’t say that I was a huge fan of the material before I took it on.

I really didn’t much care about The Shadow, I’m sorry to say. I knew the character. I had seen a couple of bad movies, but the truth is it was July of 1985. I was moving to California in September and I was trying to set up and book my work schedule for the autumn of 1985 and I took on The Shadow miniseries as an assignment. That was really it.

Dick Giordano approached me at the San Diego convention that year and asked me if I would be interested. I had nothing lined up to start my work experience in Southern California, and that’s what it was. I hate to sound like I wasn’t incredibly enthused about it. I obviously brought a great deal of effort to the material. I did a lot of research once I was committed to the project, but I can’t say that I was a huge fan of the material before I took it on.

Personally I don’t think I changed him very much at all. I took the sensibility of a man who was operating in the 1930s, who was born around the turn-of-the-century, and had him running around in a 1985 universe. I thought that he was an interesting sort of character to deal with.

We are a culture that experiences a lot of “presentism.” I am a fan of Downton Abbey, which I am sure will strike anybody as strange, but one of the things that has emerged from the criticism of the second season of Downton Abbey is a focus on all the anachronisms in the language. Yet we are a culture that imposes contemporary values on period stories.

I’ll never forget when I read one of Dorothy Sayers' Lord Peter Wimsey novels—Sayers was a Catholic theologian, who was very anti-Semitic, very much in the manner of upper class English people of that period. It was very strange for me to read about these characters, especially the way Jews were discussed. So with The Shadow I wanted to find a way to take a character out of the 1930s with all his prejudices and social beliefs and bring him to the 1980s. That was the primary adjustment I made in the character.

We are a culture that experiences a lot of “presentism.” I am a fan of Downton Abbey, which I am sure will strike anybody as strange, but one of the things that has emerged from the criticism of the second season of Downton Abbey is a focus on all the anachronisms in the language. Yet we are a culture that imposes contemporary values on period stories.

I’ll never forget when I read one of Dorothy Sayers' Lord Peter Wimsey novels—Sayers was a Catholic theologian, who was very anti-Semitic, very much in the manner of upper class English people of that period. It was very strange for me to read about these characters, especially the way Jews were discussed. So with The Shadow I wanted to find a way to take a character out of the 1930s with all his prejudices and social beliefs and bring him to the 1980s. That was the primary adjustment I made in the character.

There certainly is a fair amount of racism in the original Shadow pulp novels, isn’t there?

That is the nature of the culture of the time. I’m not excusing it. That is simply the way it was. People walked around with a set of beliefs that today have been disavowed and dismissed, but that’s the way it was. You can try and deny it and cite Jericho Druke, but let’s be serious. I just felt that it would be fun to do that character.

One of the things about doing The Shadow and taking the character into the contemporary realm (which I said at the time and which I stand by) is that the reason The Shadow is identified with the 1930s is that the character was a commercial and financial failure by the time it was cancelled. I have always believed that if Superman or Batman, for example, had ceased to exist as commercial entities in the late 1940s the way The Shadow did, they too would be perceived as “period” material. Take Tarzan for example. He was created in 1912, but no one thinks of Tarzan as a period character. He just continued to live through the times. One of the negative results of the comic fan and pulp fan’s obsession with continuity is having to find some way to justify this. I feel it is like it is. I don’t feel the need to obsess over that stuff.

I felt that doing The Shadow as a contemporary character was at that time the only viable way to make it a commercial property. I am all for people doing “forlorn hope” publishing material. For example I can’t visualize Blackhawk as anything but a 1940s property; it’s a World War II book; but I don’t think that applies to a character like The Shadow. I think that character can be updated and made viable in a contemporary context—and I think that I succeeded in doing that for the most part.

One of the things about doing The Shadow and taking the character into the contemporary realm (which I said at the time and which I stand by) is that the reason The Shadow is identified with the 1930s is that the character was a commercial and financial failure by the time it was cancelled. I have always believed that if Superman or Batman, for example, had ceased to exist as commercial entities in the late 1940s the way The Shadow did, they too would be perceived as “period” material. Take Tarzan for example. He was created in 1912, but no one thinks of Tarzan as a period character. He just continued to live through the times. One of the negative results of the comic fan and pulp fan’s obsession with continuity is having to find some way to justify this. I feel it is like it is. I don’t feel the need to obsess over that stuff.

I felt that doing The Shadow as a contemporary character was at that time the only viable way to make it a commercial property. I am all for people doing “forlorn hope” publishing material. For example I can’t visualize Blackhawk as anything but a 1940s property; it’s a World War II book; but I don’t think that applies to a character like The Shadow. I think that character can be updated and made viable in a contemporary context—and I think that I succeeded in doing that for the most part.

How did you feel about his mystical powers, his ability to cloud men’s minds, that seems like a real period touch?

That sort of thing actually waxed and waned in the pulps; it was an aspect of the radio character more than anything. I was more interested, frankly, in the guns and the sense of moral terrorism that The Shadow could lay out. I was always a Batman fan rather than a Superman guy. I was always for the guy who put himself through the work and effort to achieve, rather than just have it handed to him. So I like non-super-powered costumed characters more than I like super-powered costumed characters. So I tended to emphasize the aspects of The Shadow that were those of a mortal man who had trained himself to be a superhero.

Which secondary characters did you keep from the 1930s?

Well very much Margo Lane—I envisioned Margo Lane as a very embittered, angry woman who resented the fact that she had been deserted by the love of her life at the peak of her life; a woman who in retrospect had pissed away her entire experience waiting for this guy to come home. He comes home and she’s an old woman in her 70s, and he still looks like he did in 1938.

Were you influenced in your portrayal of an embittered middle-aged hero by The Dark Knight Returns?

No, I don’t think The Dark Knight Returns had even come out when I was working on The Shadow (note: The Dark Knight Returns didn’t debut until February of 1986). I was aware of what Frank was doing there, but I was more aware of how he was influenced by me in his use of television screens to push the narrative. In The Shadow material I was more interested in kinetic layouts.

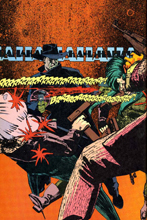

I remember The Shadow: Blood & Judgment as being very violent—with the head shots and amount of blood--is there any influence of the films of Sam Peckinpah like The Wild Bunch?

I found that as I read the original Shadow stories, it was a pretty violent experience (it was the pulps), and I was good with that. The depiction of violence—well I should explain that I am a total pussy. I am a physical coward and a total chickenshit. I like drawing violence, there is something balletic about it—there may an indirect Peckinpah influence there, but I don’t think it was a direct influence. It was the cultural effluvia of the time.

Looking at Blood & Judgment again we were struck by your use of a lighter tonality, rather than the sort of clichéd dark film noir shadow-heavy look. That was a conscious choice on your part, wasn’t it?

Absolutely. One of the commitments that I have always taken with my material is that my villains are at least as attractive physically and emotionally as the heroes, and I felt that the 1980s was an era of sleazy slimebags who portrayed themselves as positive influences—I give you the President for example. The Reagan years were very difficult for me. I’m not one of who walks around wondering if Ronald’s going to come back and save us. Not five minutes ago I was talking to my assistant and I paraphrased Sinclair Lewis who said that when fascism came to the United States it would be “holding a cross and wrapped in the flag,”—and to a certain extent that was how I felt in the 80s.

The pastel nature of The Shadow was very much an attempt to convey the sleaziness of the 1980s. It was also the first thing I did after I moved to California. It was a different work experience. It was a beautiful autumn in Southern California. It was an enchanted time for me; it really was. All that affected me in very positive ways. I was really happy.

The pastel nature of The Shadow was very much an attempt to convey the sleaziness of the 1980s. It was also the first thing I did after I moved to California. It was a different work experience. It was a beautiful autumn in Southern California. It was an enchanted time for me; it really was. All that affected me in very positive ways. I was really happy.

How does your version of The Shadow differ from the earlier ones that you researched?

I think it has irony, which I think the other versions of The Shadow do not. I am a great believer in irony and humor as a leavening force for material. For the most part comic book fans and many comic book writers tend to conflate and mistake “gravity” for “enormity,” and I’m not particularly grave. I have an aversion to gravity, but I am a big fan of enormity.

I feel that, as you so often hear during Academy Award season, comedies don’t get the attention that they deserve because they are not considered serious films. I think that is true in the context of what we do in the comic book business as well. There is this mistaken idea that if a serious tone and attitude is achieved that the material must, by dint of that, actually be serious and important, but that is a very adolescent view of adulthood. What I tried to do with The Shadow was create irony in an irony-free product. That was my job as I saw it, rather than a one-dimensional idea about heroism, about social danger.

Take a look at the Batman franchise for example. Batman is about a guy who had a rough day when he was eight, who has been kicking the living shit out of people he doesn’t know since then. He can identify evil by the way it looks. There’s no irony there. In the real world, if Bruce Wayne were real, he would be arrested—-a bondage freak dressing up in leather and beating up people he doesn’t know, because he knows they are bad. If he were truly interested in positive change, he would invest all that money he is spending on the Batmobile and all that other cool stuff in helping people, but that isn’t particularly heroic or very interesting, so you have to find a way to achieve irony in the context of this material. That’s the job for me. That’s how I approach it.

I feel that, as you so often hear during Academy Award season, comedies don’t get the attention that they deserve because they are not considered serious films. I think that is true in the context of what we do in the comic book business as well. There is this mistaken idea that if a serious tone and attitude is achieved that the material must, by dint of that, actually be serious and important, but that is a very adolescent view of adulthood. What I tried to do with The Shadow was create irony in an irony-free product. That was my job as I saw it, rather than a one-dimensional idea about heroism, about social danger.

Take a look at the Batman franchise for example. Batman is about a guy who had a rough day when he was eight, who has been kicking the living shit out of people he doesn’t know since then. He can identify evil by the way it looks. There’s no irony there. In the real world, if Bruce Wayne were real, he would be arrested—-a bondage freak dressing up in leather and beating up people he doesn’t know, because he knows they are bad. If he were truly interested in positive change, he would invest all that money he is spending on the Batmobile and all that other cool stuff in helping people, but that isn’t particularly heroic or very interesting, so you have to find a way to achieve irony in the context of this material. That’s the job for me. That’s how I approach it.

The design of Blood and Judgment is especially interesting, could you comment on what you were trying to achieve?

I’ve always felt that the strongest suit I have as a comic book creator is my design and layout sensibility. I’ve invested years in trying to come up with different interesting ways to tell stories visually using panels as an element of the time aspect. I’ve been influenced by everything including the works of Stephen Sondheim and musical theater, which is a big part of my background—and yet I hate Glee. I am always looking to find new ways to tell stories visually.

I recently heard an anecdote about one of my colleagues, a comic book writer, who apparently believes that the artist has absolutely nothing to do with the creative process in comics. If the artist is drawing realistic people in realistic situations, he is simply doing a job of work rather than participating in the creation of the material. I am of the belief that the artist does 50% of the “writing” in comic books. I think the guy is plum crazy. It staggered me in its limited understanding of what comic books are about.

For example Watchmen is always being referred to as Alan Moore’s Watchmen as if Dave Gibbons had nothing to do with it. But the sensibility of that book would have been an entirely different experience if someone besides Dave had drawn it, and I don’t think that Dave gets near the credit and props he deserves. I think that it is important to acknowledge the fact that comics is a visual narrative medium in which much of the “writing” is provided by the artist who visualizes the material.

I recently heard an anecdote about one of my colleagues, a comic book writer, who apparently believes that the artist has absolutely nothing to do with the creative process in comics. If the artist is drawing realistic people in realistic situations, he is simply doing a job of work rather than participating in the creation of the material. I am of the belief that the artist does 50% of the “writing” in comic books. I think the guy is plum crazy. It staggered me in its limited understanding of what comic books are about.

For example Watchmen is always being referred to as Alan Moore’s Watchmen as if Dave Gibbons had nothing to do with it. But the sensibility of that book would have been an entirely different experience if someone besides Dave had drawn it, and I don’t think that Dave gets near the credit and props he deserves. I think that it is important to acknowledge the fact that comics is a visual narrative medium in which much of the “writing” is provided by the artist who visualizes the material.