As SLG turns to crowdfunding to meet basic costs, is there a better model for arts-oriented indies?

As SLG turns to crowdfunding to meet basic costs, is there a better model for arts-oriented indies?Last Thursday, Slave Labor Graphics (SLG) publisher Dan Vado put out the word that he had launched a campaign on the crowdfunding platform GoFundMe to raise $85,000 to help get his business back on its feet.

"A perfect storm of bad luck, bad economy and, yes, bad decisions have left the company on a terrible financial footing," wrote Vado, explaining the motivation and purpose of the campaign. SLG had recently extended its credit during a relocation, and when the bank called in the loan, "this created a domino effect where, when reporting the change in my credit status to the various credit bureaus caused them all to cut my credit and in a couple of cases close my accounts," according to Vado.

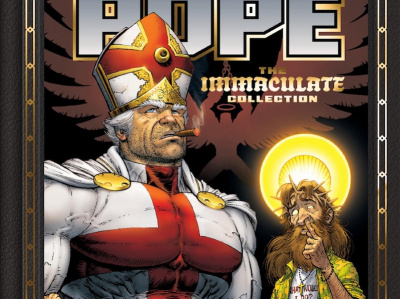

Starved of the funds to operate, the longtime publisher of indie classics including Milk & Cheese, Johnny the Homicidal Maniac, Lenore and Emo Boy faces bankruptcy unless the community steps in with support.

Help us Obi-Wan, You’re Our Only Hope. This is the second time in a year that alt-comics readers have been asked to ride to the rescue of a publisher facing economic distress. Last fall, Fantagraphics took to Kickstarter to crowd-fund its spring and summer 2014 lineup in the wake of turmoil following the untimely death of co-publisher Kim Thompson.

Fantagraphics’ approach, which essentially pre-sold planned titles in exchange for the money necessary to complete them, is different from SLG’s, which is soliciting good-will support only. But both reach outside the traditional mechanisms of the market economy to finance businesses that would seem on their own not to be commercially viable--or at least not viable enough to survive a “perfect storm.”

The new normal. Fans who still value the things that Fantagraphics, SLG and other small presses bring to comics and don’t want to see these companies pay the ultimate price for bringing experimental, non-commercial work to market may need to get used to this mode of operation, just as fans of the classical music and theatre are already accustomed to fund-raising pleas by producers of those kinds of events, over and above the cost of tickets.

Culture, contrary to prevailing assumptions, isn’t free. Creators of this kind of work don’t need to make a killing, but they do need to make a living. Crowdfunding is our 21st century “gift economy” approach, but is there a more straightforward way?

Indy Comics as a Cultural Enterprise. The difference between a business like SLG, which is soliciting support from "readers like you" to pay its bills in order to continue serving a niche market, and your community theatre, which does basically the same thing in a more systematic way, is how they are organized. Chances are, a cultural enterprise like a visual arts space or performing company is set up as a non-profit under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code.

There are some important differences between actual, official non-profits and ordinary businesses that happen not to be profitable. First of all, money you donate to a non-profit is tax deductible, which makes a difference, especially for well-healed donors. Second, non-profits enjoy certain privileges in terms of exemption from taxes and fees. Finally, non-profits can make more extensive use of volunteers and interns making subminimum wage. This last bit might be important for on-the-edge businesses in jurisdictions where hikes in the minimum wage are forthcoming.

To qualify for these benefits, non-profits need to adhere to some strict rules. They can’t distribute excess revenues as profits to owners or partners (that’s what makes them "non-profits.") They can’t engage in political activities or lobbying. Most of all, non-profits are defined by their mission, not their financial success, and if they stray too far beyond that mission, especially in areas that generate revenues, the IRS will come after them with a vengeance.

Contrary to popular perception, however, being a non-profit doesn’t mean you can’t make money. Lots of successful non-profits generate revenues in the millions and pay their staff, executives and contributors salaries comparable with those in the private sector. They can also pay contractors and contributors like performers or creators full market rates. They just don’t pay shareholders, and they plow any excess revenues back into their operations.

Can publishers be non-profits? Yes they can. According to the IRS, "Publishing activities may be a means of attaining an exempt purpose." Though this most often applies to religious and educational publishers, there are also a number of literary presses that operate as non-profits.

Milkweed Editions offers a full line of fiction, non-fiction, poetry and young adult titles indistinguishable from those of a commercial press, but explains that "our mission is to identify, nurture and publish transformative literature, and build an engaged community around it. As a nonprofit organization, Milkweed Editions depends on the generosity of institutions and individuals, in addition to revenue generated by sales of the books we publish. In an increasingly consolidated book business, this support allows us to select and publish books on the basis of their literary quality and transformative potential."

Archipelago Books is another press whose output shows that "non-profit" status does not necessarily mean poverty row production values or some kind of second-class opportunity for authors.

There’s even an example in the comics industry: Prism Comics, "a nonprofit organization that supports lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) comics, creators, and readers." Though primarily an advocacy organization, Prism publishes an annual guide to LGBT comics and funds independent creators through the Queer Press Grant.

Non-profit status for a low-profit segment. In a marketplace where independent comics publishing has, for all intents and purposes, become a cultural rather than a commercial endeavor anyway, could non-profit status formalize this situation and give mission-driven publishers (and their fans) more tools to keep the doors open beyond the occasional crowdfunding campaign?

I reached out to Vado on this question and his answer was illuminating. "A non-profit model for a company like SLG would make sense, but I did not consider it until you mentioned it. The advantages go beyond simply tax-deductible donations: non-profits pay less for postage and are exempt from many taxes and fees."

"However there are restrictions too that would make it difficult for a publishing company to be a non-profit, and in general anything that was started as a for-profit endeavor to switch to being a non-profit as it can be seen as a tax dodge."

"It would be good advice for a start-up though."

Yes. Yes it would.

--Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture and a business consultant in Seattle.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.