We recently caught up with one-time Marvel COO Bill Jemas, who’s now at Double Take (2T), the new comic publishing imprint from video game publisher (Grand Theft Auto, Bioshock) Take Two Interactive (see "Former Marvel COO Jemas Back in Comics"). The company recently announced its first titles, which take place in a common creative universe (see "Double Take Launches 10 Titles in September"). In Part 1 of our two-part interview, we talk about how the comic publishing world has changed since Jemas’ Marvel tenure (2000-2004), his thoughts on overprints and variants, and on launching a new comic company in the current environment. In Part 2, we talked about the launch issues of pricing, accessibility, marketing, digital, and the talent.

You’ve got a unique perspective on the market. You ran Marvel’s publishing 10-15 years ago, have been adjacent to the comic book business since, and are now jumping back in with both feet. How do you think the business has changed in that time?

I guess my surprise coming in was how well some of the independent companies and creators were doing in terms of sales volume. In talking to the handful of the guys who do creator-owned pubs, either self-published or self-published through Image, I was expecting them to be doing better financially. I think my surprise with the industry is that it may not be providing a living for as many people as it could be or should be. Without naming names (I don’t want to embarrass people), looking at sales numbers from independent guys that score really high up in the monthly charts and understanding how much money is left for the creative team, when all is said and done not much is left. So that was a bit of a shock.

But I think the other things were not surprises. It’s very hard to make money as an independent publisher. The math just doesn’t work. Good indies [move] 10-15 thousand units. If you want to pay people the way Marvel and DC does, you’re spending $10-$15 thousand for art and editorial, and then by the time you get done paying that and you’ve got $.50 to $1 a book you have to pay at low print volumes, you’re just losing money on every book if you’re successful, which is an interesting way to define success.

The companies that are crafty find a way to make money through a whole bunch of other ancillary sources of revenue: obvious and easy, graphic novels; just as obvious but less easy, TV and movie deals; and then finally licensing. But at Double Take, our charter is to build properties from scratch so we’ve had to shuffle the model a little bit to make it make more sense, to give us a reasonable chance at long-term profitability.

You’ve described a pretty daunting environment for a new publisher. What is your take on Double Take’s business model in that tough environment that you’ve just described?

There’s a Steve Martin joke: "How you can be a millionaire and never pay taxes? The first step is you get a million dollars." Our first step was to get sponsorship by a well-heeled company who understands that it can take some time to brew up a good entertainment business. Really the first step and what’s kept us going through these two years and change without publishing anything is a lot of support from the guys at Take Two. Some of that has just been giving me and my team the time to learn how to build properties from scratch. That’s been really hard to do. It’s been an intellectual challenge. As some of us know, as you get older, those intellectual challenges take a little bit longer, but I think we’re there on the creative side.

From a pure ink, paper, sales side, what we’re doing is a little bit higher risk but certainly higher reward. Very specifically, we’re not trying to peg our initial print runs to initial orders. We’re going ahead and printing enough books so that we get really good prices from the printer, so we can have a low retail price point, get new readers in, and still sell to the retailers at a good enough price so they have a decent margin.

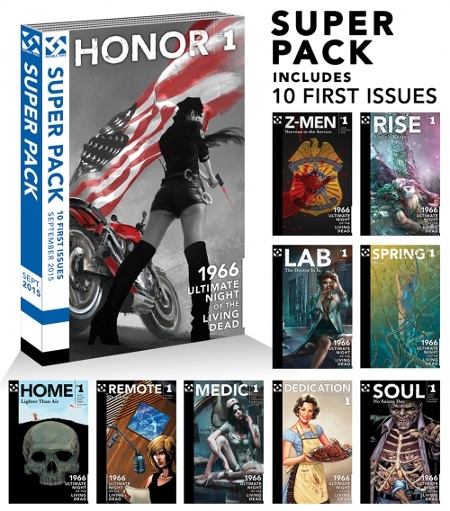

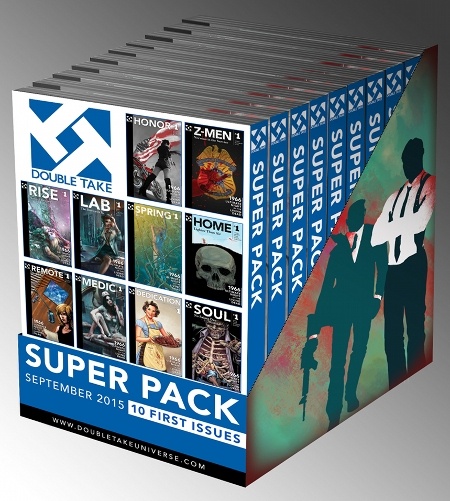

So we’re gang-printing the first 10 books, and (this coming out of my mouth will shock you) overprinting, printing what we think will sell in a long run with the first issues as opposed to what we sell in the first pop. Once we had all 10 books in mind, we thought, we can trickle them out once a month, 5-10 thousand units, or we could gang them together in one big Super Pack.

What we’re doing is taking the 10 first issues and ganging them together in a Super Pack, shrink-wrapped with a spine, and loading all of those in a display shipper that fits countertops. So a retailer can buy the units, not blow any shelf space (not that counter space is easy, but shelf space is gold), put our 10-packs in a display case and sell them at a reasonable price, and when there’s one or two units left, they can take the Super Pack and place it spine out where the graphic novels go.

We think this is a nice model. You never know until you know, but crystal ball out, this feels good. What I can tell you about it, with 10 individual #1s trickled out one at a time, I was pretty sure that even if we had pretty good books, we’d lose money. With this system, I’m pretty sure that if we have pretty good books, we’ll make money, the retailers will make money, and the fans will get a decent price.

This kind of thing is exciting. My boss asked me yesterday how I’m feeling and I tell him I’m feeling nervous and I’m not sleeping, and for me, that’s good. That means we’re working hard on this and we’re doing everything we can to get the best stories out there and carry through the rest of the way through the printing process so the reader’s experience is good overall.

You mentioned that people may be surprised at the fact that you are overprinting. You famously ended overprints at Marvel when you were there, and the collectible market responded (see "Jemas: Marvel's No Overprint Policy Is 'IQ Test for Comic Retailers'"). Is this different approach due to a perception of a change in the collectible market or is it just a different situation for Double Take vs. where Marvel was then?

That’s the other surprise when I re-entered the industry. The team that left with me and the team we left in place, there was a nice model for making money for everybody, the no-overprint, no-reprint model.

As I got back to the industry, I had a handful of retailers who called and said, "Bill, you know we owe you one." They send me a picture of a beach house and say, "We built that with the money we made when we got back into collectability." So I would have expected that Marvel would have kept up with no overprints, no reprints, and that DC would have copied, and the industry would have had, in addition to the pure readership, a collector’s aspect. And frankly, if you’re doing print in the era of DoD [Download on Demand], you’d better have something. So I was a little surprised that something that was really teed up and ready to go and worked really well disappeared. I don’t know why, and haven’t talked with the guys about why they did what they did, but it’s a shame.

With respect to us specifically, we are going to take a guess at what the books ought to sell, and we’re going to print that amount, and that’s all we’re going to print. The difference is that we’re not expecting the books to become collectible on the first day. We’re building up some inventory. We’re talking to the top retailers in the industry, and a handful of we’ll call them, affectionately, whales (a handful of serious collectors) about taking a position with the books and buying a bunch of them, and selling them out slowly.

I think we’ll get to collectability. It didn’t make sense to me to think that we’d get collectability from obscurity. I thought the books should get out there, people get to like them. If people like them as much as we hope they do, there’ll be a chase and the books that we’re printing the first shot will sell out quickly and have a secondary value to prime the pump for the collectibles business in the long term.

I’m not a collector; I love the collectibles business. I think it’s a lot of fun. I’ve lived through the abuses. I lived through Fleer. We had a wonderful business, and we got the rug pulled out from under us by the parent company with overprinting, but when collectability’s working, people have a good time doing it and retailers can make a pretty solid living brokering collectibles.

One difference now is that some of that collectible aspect of the market is in the variants portion of the business. Are you doing any variants? How do you feel about those?

I don’t believe in them. As I look back at the products that I’ve produced, and the products that were produced when I was the most active in the business (books like Ultimate Spider-Man, which is just the stuff inside), you take the risk, you buy the book. You don’t have to buy this and that and the other thing, you just get the one book. Those seem to have held value, or I’ve perceived them to have held value.

I don’t like variants. I think it’s a lot of work with not a lot of value. If we do any variations, we might take one story, one premise and build two beginnings off the same premise; we might build two alternate universes into the same world. So we might have alternate insides, but I don’t think alternate covers are all that healthy. Everybody who bought Origin #1, got Origin #1. It’s a collectible book now it’s a lot of fun to have. We didn’t do the variant. The books that had the variants didn’t hold value.

I’m also harkening back to my experience with trading cards where the plain vanilla, in-the-pack Michael Jordan rookie card’s worth a lot of money and all the b.s. that we created of variant Michael Jordan stuff didn’t really matter.

Click here for Part 2.

What's Changed since Marvel, Overprints, Variants

Posted by ICv2 on July 1, 2015 @ 3:02 am CT