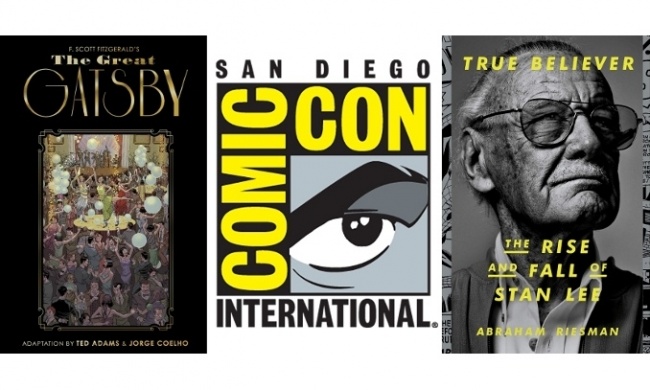

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past. Last week I got a preview of the upcoming comic adapting F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, written by Ted Adams with art by Jorge Coelho and colors by Ines Amaro, upcoming from Clover Press. The story is fresh and well-paced, faithful to the original without feeling too Classics Illustrated, and the artwork is flat out gorgeous. And in case you can’t get enough of the 1925 novel that some people consider the finest work of American literature, boutique publisher Beehive Books is kickstarting one of their deluxe illuminated editions with new artwork by the Balbusso Twins. And these probably won’t be the last Gatsby adaptation announced this year.

That’s not a coincidence. The Great Gatsby and all other works published in 1925 just entered the public domain, which means they can be published and adapted without the need to seek the copyright holder’s permission or pay a royalty. Gatsby is by far the highlight of this year’s class, which also features some early work by Ernest Hemingway, Agatha Christie, Aldous Huxley, and Theodore Dreiser’s proto-true crime novel An American Tragedy.

As the legal curtain comes up on some of the pivotal works of the Jazz Age, it’s worth noting that copyright protection didn’t always extend nearly a century. Originally, in the United States, it protected works for only 14 years. It was subsequently extended to 28 years, then to 75 years or the life of the author plus 50 years. Thanks to California Congressman Sonny Bono working on behalf of his prominent constituent, The Walt Disney Company, it was extended again in 1998 to 120 years or the life of the author plus 70 years – ensuring that valuable corporate-owned IP would not fall into the public domain for a century or more.

Economist Dean Baker recently made a persuasive argument that intellectual property protection such as patents and copyrights, when extended to such lengths, constitute a regressive tax distributing resources upwards from consumers to the narrow class of rights-holders, including some of the world’s wealthiest corporations. He advocates a looser regime to make the idea economy more open, and also to ease tensions over IP law with foreign competitors like China.

Before you dismiss that as wooly-headed idealism, it’s worth remembering that IP law in the first instance wasn’t intended to protect corporate profits or even creators necessarily; it was to ensure that the public would benefit from a steady stream of original works and ideas by guaranteeing innovators a period of exclusivity in which to benefit from their work. After that reasonable period expired, the work would enter the public domain so that others could use it as the basis for their own creations and adapted works, because that’s how culture usually works. One of the great believers in this approach of creative appropriation was none other than Walt Disney, whose animated features gleefully plundered the treasure chest of folklore and the favorites of earlier generations.

Thanks to companies unwilling to let loose of their cash cows, we in the 21st century now have to wait almost a hundred years for works to come onto the free market. Luckily, we’re the beneficiaries of some inspired new takes on now-dusty old classics.

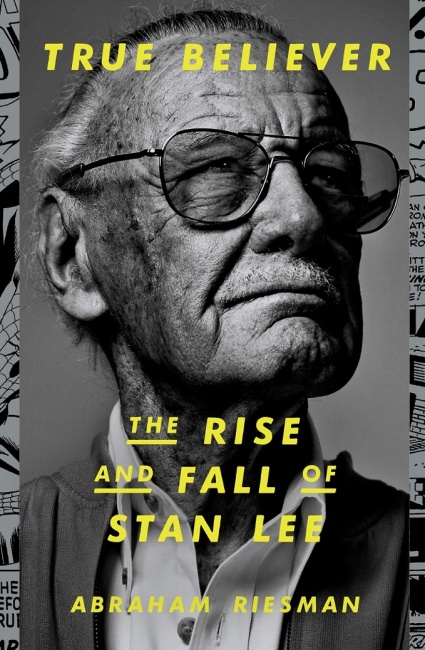

The Rise and Fall of You-Know-Who. Speaking of self-created hucksters and people who benefited massively from the current IP laws, you may have heard there’s a new biography of Stan Lee out this month: True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee by Abraham Riesman. I wrote a full review a few weeks ago over at Forbes, before anyone had gotten a look at the actual book. Now that it has hit the streets accompanied by a veritable marching band of press attention, it has become, predictably, the subject of intense discussion in the comics community. Because nothing says "third rail" like wading headlong into the question of "who created the Marvel Universe?"

The Stan book isn’t some drive-by hit piece as it is being portrayed in some quarters: though Riesman writes for Vulture, he doesn’t personally prey on the dying. Just about every part of the book is extensively researched by someone who is both a professional journalist and a knowledgeable member of the comics community; there are facts revealed in it that even 50 years of prior comics scholarship have failed to turn up.

We’re not used to seeing Stan portrayed in harsh overhead light, as opposed to the limelight he’s basked in for the latter part of his career. Stan’s reputation as the amiable ambassador of comics is so pervasive, and the "Stan Lee Presents…" mindset so strongly embedded in the public that any hint of skepticism about his ethics or his accomplishments can trigger a defensive response.

Let me submit that the reason Stan Lee is worth a handful of biographies, including Riesman’s, and that his career is due so much scrutiny, is because he really was a singularly important figure in 20th century culture. Without him, warts and all, there would be no Marvel, no connected universe of fallible superheroes, no celebrity status for makers of comic books, and likely no special place for comics-based content in the wider media and entertainment universe. We may know he didn’t do it alone, but the rest of the world doesn’t.

It’s important to unpack his claims and examine his career because misunderstanding his real impact on the business could lead to some mistaken conclusions about the process of creative collaboration in visual media, misunderstandings that benefit not just people like Stan Lee, but companies like Marvel and Disney that prefer a simple narrative about creation that supports their ownership claims.

Love Stan or hate him, love Riesman’s book or hate it, the project itself is important and the conversation it’s starting will probably help in the long run.

We’ll meet again, don’t know where, don’t know when. While we’re dwelling on great things that are gone, let’s reflect on completing our year without in-person conventions, expos, trade shows, festivals or meetups – a year that, unfortunately, will extend at least through mid-summer with today’s announcement that CCI is pulling the plug on its second straight San Diego Comic-Con (see "San Diego Comic-Con Canceled for 2021").

Last year at this time, ReedPOP’s C2E2 brought tens of thousands to McCormick Place in Chicago, and while a few people might have nervously been reading the stories of an outbreak of a new pulmonary virus from China at a nursing home outside of Seattle, it’s unlikely anyone foresaw what was coming.

A week later, I was at the intimate San Diego Comic Fest, which would turn out to be the largest convention held in San Diego in 2020. At one panel, I interviewed SDCC’s David Glanzer, who remained optimistic that WonderCon, scheduled for a few weeks later, would still be held. It wasn’t. Neither was Emerald City Comic Con, or SuperCon, or PAX, or E3, or SDCC.

In missing out on those events, the industry lost more than just the revenues and attention that shows generate. We also lost out on the camaraderie and collaborative energy that keeps often-solitary creators going, and that’s a gap we’re likely to feel even after we return to live events because of the lead-time that projects generally take to come to market.

With the approval and rapid rollout of vaccines, there may finally be reason to believe that we will, cautiously, be popping our heads out from our bunkers. The market is already pricing in a return of outdoor festivals by summer, and ReedPOP has scheduled the 2021 editions of C2E2 and ECCC for December. Even as SDCC regretfully scrubbed its summer show, it has teased the possibility of a three-day live event in November.

Here’s hoping that, before long, we’ll be seeing each other again some sunny day.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.