Three weeks after the shocking story in Vulture raised the curtain on Neil Gaiman’s personal life, the industry is still feeling the repercussions. Last week Dark Horse Comics, publisher of many of Gaiman’s recent projects including Anansi Boys, announced it was ending its relationship with the author (see "Dark Horse Ends Relationship with Neil Gaiman"), and the estate of Gaiman’s Good Omens coauthor Terry Pratchett confirmed that Gaiman will not receive any of the proceeds of the $3 million Kickstarter campaign to fund a graphic novel adaptation by Colleen Doran (see "Gaiman No Longer Affiliated with Good Omens Graphic Novel").

This follows the cancellation of most of Gaiman’s ongoing media projects, most recently the announcement by Netflix that the forthcoming second season of Sandman would be the last. This follows the Sandman spinoff Dead Boy Detectives into oblivion, as well as the truncated finale of Amazon Prime’s Good Omens.

In an age where "cancel culture" has faced backlash in some quarters, there is not really much debate about this example. Although Gaiman has denied that any of the sordid activities discussed at great length in the Vulture story, or previously on the "Master" podcast on Tortoise, were nonconsensual, the behavior he has not denied is bad enough to have just about everyone recoiling in disgust. And of course, there is no reason for anyone to accept Gaiman’s denials over the detailed, mutually corroborating accounts from several otherwise-anonymous women who have nothing to gain coming forward against one of the most beloved and influential figures in modern literature.

Outside the comics business, this is just one more example of someone whose bad behavior finally caught up to him. Lord knows we’ve had enough of those examples, even if some of the worst ones ultimately got away with it. But inside our industry, the consequences are more dire and more personally felt.

The bigger they come… A lot of the time, when a public figure is revealed to have feet of clay, the fault lies as much with the people who built them up and idolized them. We are taught in school to separate the artist from the art. But when the creator of darkly beautiful troubling work turns out to be a dark, troubled person who behaves badly or expresses odious opinions, some of that is on us for expecting too much.

It’s a little more complicated in this case. For nearly 40 years, Gaiman made his legacy as much about being a good guy as being a great writer. He not only elevated the artform of comics by giving us imaginative and gorgeously-crafted work, he also elevated the industry by speaking out on behalf of creators, free speech, marginalized people and business practices he saw as destructive.

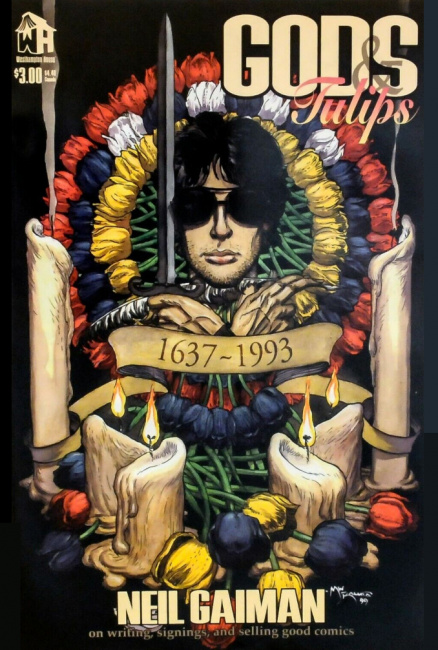

Gods and Tulips, a slim collection of essays and speeches from the late 1990s addressed to an audience of retailers, creators and professionals, accurately diagnosed many of the problems that comics were having in that era. The book was collected as a benefit for the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, the free speech organization that Gaiman served as a member of the Board of Directors and visible spokesman for many years.

He was generous with his time with fans, doing readings and signings that could last for hours on end. He wielded his massive influence on Twitter and other social platforms to confront bullies and counterprogram other figures in the fantasy literature field with less inclusive views on gender issues.

In short, he worked it. His personal brand made people feel good about supporting his projects, which made those projects more valuable and culturally resonant. Netflix paid hundreds of millions of dollars for The Sandman, which had a production budget of over $15 million per episode. Part of that was a bet on the value of the property, but surely a significant percentage hinged on the fact that it was Neil Gaiman’s Sandman and the worldwide legion of fans who hung on his tweets, his winning persona, and his mellifluous voice would gladly part with the monthly subscription cost to see his magnum opus brought to life.

The harder they fall. Against this carefully constructed public image of concern, empathy and engagement, we suddenly get the most dissonant possible counternarrative: someone who, in certain personal interactions, is not just callous and manipulative ("selfish" is a word he used in his brief public mea culpa), but literally gets off on acts of degradation and cruelty.

This isn’t intended to kink-shame. Who can judge how people are wired sexually? But those of us who made it through the painfully explicit Vulture story are left with a vision so deeply at odds with everything Neil Gaiman himself led us to believe about his emotional makeup that even people who have known him personally for decades were left stunned and horrified. It is simply not possible to listen to his inspirational "Make Good Art" commencement speech from 2012, or really any of his utterances whatsoever, without feeling that we have fundamentally been lied to and manipulated.

That is different in both degree and kind from other examples of artists whose behavior ranges from disappointing to horrifying. Say what you want about Harvey Weinstein, but no one ever claimed he was some kind of paragon. Figures on the far right preach public morality while doing gross things in private, but most of them seem like pretty awful people and some of them even glory in that persona. I think most people who encountered Neil Gaiman personally or professionally found him to be a nice, reasonable, highly intelligent guy, at least if you weren’t one of his sexual targets. There is something existentially shattering about realizing there is a Mr. Hyde behind someone who spent so much time cultivating his image as Dr. Jekyll.

The blast radius. Given the nature of the revelations and the insufficiency of Gaiman’s response, it’s hard to see how he and or his work comes back from this. Part of that is his problem, although he’s probably done well enough financially that he’ll be ok even if his work never makes him another penny.

The rest of the comics business is not so fortunate. This disaster radiates out in concentric circles, starting most unfortunately, with his collaborators on current projects. Colleen Doran, who has spoken out loudly and often about issues of sexual misconduct in the comics business, has done gloriously beautiful artwork in service of Gaiman’s stories for decades: not just the forthcoming Good Omens book, but also Eisner-winning material like Snow, Glass, Apples, Chivalry, American Gods and stories dating back to the original Sandman run. Their work together was recently the subject of a gallery exhibition at both the New York Society of Illustrators and the Comic-Con Museum.

Marc Bernardin and Shawn Martinbrough have both been doing great work on Dark Horse’s Anansi Boys, which will now be canceled an issue short of its conclusion and won’t be collected into a trade.

DC Comics has not yet said anything, but it’s hard to see how they can keep the perennial best-selling Sandman trades or omnibi in print, which is likely to affect the income of his many artistic collaborators.

Publishers themselves are going to take a haircut as well, of course. So will retailers stuck with nonreturnable inventory. How many comic shops featured Gaiman’s work as face-outs and endcaps as a way to capitalize on his larger cultural cache and visibility? And then there are the crews of the cancelled shows.

For Gaiman’s fans and believers, we are now treated to an onslaught of "woke author was secretly abusive pervert" stories from exactly the people Gaiman stood against, at a particularly inconvenient moment to have a progressive cultural figure discredited.

Moving on. This is a tough thing to write about because I counted myself among Gaiman’s admirers, not just for his art but for everything he did for the business and the culture. His approach to comics resonated with me and helped bring me back into the fold in the mid-90s after a long break. My few personal encounters with him were enjoyable, and some of my best friends in comics are people who were close with him for years. I suspect I’m not alone in this.

Out of basic humanitarian concern, I hope that Gaiman gets whatever help and support he needs for his own mental health moving forward. But beyond that, it’s impossible to view this as anything but a complete tragedy for the victims, the industry, the fans and the culture.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture and a two-time Eisner Award nominee.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

Posted by Rob Salkowitz on February 3, 2025 @ 3:23 pm CT