Rolling for Initiative is a weekly column by Scott Thorne, PhD, owner of Castle Perilous Games & Books in Carbondale, Illinois and instructor in marketing at Southeast Missouri State University. This week, Thorne explains which games publishers shouldn’t bother trying to sell him.

I followed a discussion on Facebook for the past couple of days focusing on games launched through Kickstarter and why they not only did not need retail storefronts to sell their game but actually avoid them, failing to see any value in what the retail storefront offers. By handling the shipping functions, they get to keep the part of the profit they would otherwise pay to the distributor and retailer for their services (and believe me, distributors and retailers do provide services for the share of the profits they receive, but that’s another story). For most of those small publishers, they are right. They don't need my store to sell their game.

From discussions I have had with others in the industry, we have roughly 1,500 to 2,000 dedicated gaming stores. This includes shops that focus on trading card games but excludes the big box stores such as TRU, Barnes and Noble and Target that carry board and card games but would view a day's sales of them as a rounding error in the total.

For a small press game (which frankly most Kickstarted games are), unless you go the Print on Demand route, in order to keep costs as low as possible a publisher plans for a print run of between 1000 to 5000 or so copies. There's pretty poor pricing until you hit the 2000-3000 copy mark, meaning lower profit per unit, all through the channel. In a case like this, barring such special circumstances as a local fan base, it is probably better for the publisher to print in smaller quantities, increasing the cost but allowing them to skip the store and sell direct while making comparable levels of profit. Without pre-sales, this means a lot of copies left over from the initial sales push. However, the "long tail" of the internet makes it possible for those extra copies to sell eventually, rather than get sold as remainders.

The long tail is a marketing concept that developed to explain how companies like Amazon and Netflix can offer millions of products and still remain profitable. Essentially, it's the 80/20 rule extended (You remember the 80/20 rule: 80% of sales come from 20% of products). The long tail says that comparatively few products account for the majority of a company's sales and that the vast majority of them only sell a few units per month or even year. Since the marginal cost of adding a new item listing to a website is next to nothing and the cost of storage has dropped dramatically over the past decade (Digital storage costs are minute and more companies are using Fulfillment by Amazon, piggy backing on Amazon to drastically cut their storage costs), small press companies can much more easily make a profit while conversely selling fewer copies of a game to do so, meaning that at this point, they don't really need to sell to me. It's when demand for the game outstrips the ability of the publisher to also handle sales that distributors and retailers provide the needed services.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Column by Scott Thorne

Posted by ICv2 on January 12, 2015 @ 1:36 am CT

MORE GAMES

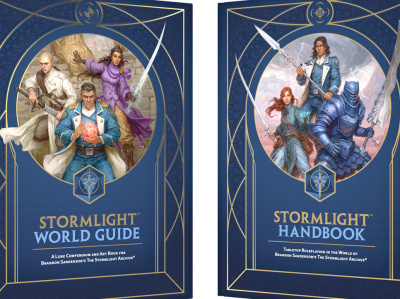

For 'Cosmere Roleplaying Game'

August 13, 2025

Brotherwise Games will be launching the Cosmere Roleplaying Game: Stormlight series.

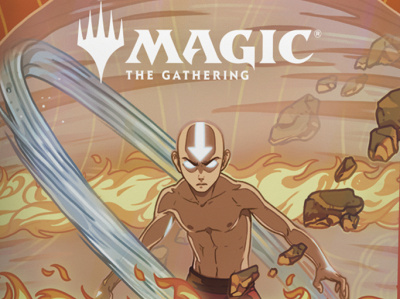

New Set Features Lots of Allies and Humans

August 13, 2025

Wizards of the Coast revealed details on Magic: The Gathering - Avatar: The Last Airbender.

MORE COLUMNS

Column by Scott Thorne

August 11, 2025

This week, columnist Scott Thorne notes a new twist in the Diamond Comic Distributors saga and shares his thoughts on the Gen Con releases that will make the biggest impacts.

Column by Jeffrey Dohm-Sanchez

August 7, 2025

ICv2 Managing Editor Jeffrey Dohm-Sanchez lays out the hotness of Gen Con 2025.