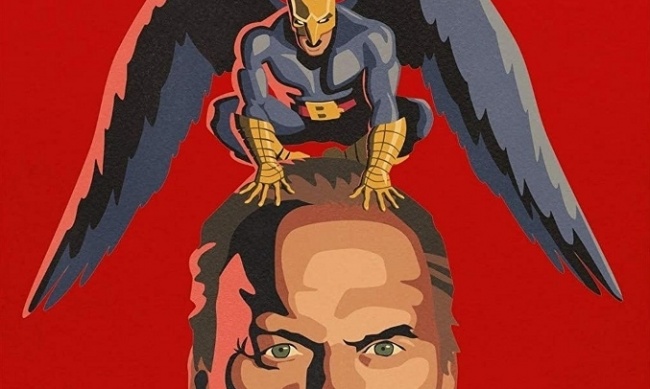

Flight of fancy. In case you missed the film (minor spoilers ahead), Birdman follows a middle aged actor named Riggan Thomson, played by Michael Keaton, who’s long-ago claim to fame was playing the superhero "Birdman" in a typical Hollywood mega-blockbuster. Despite achieving commercial success, Riggan walked away from the role and proceeded to make a mess of his life, alienating his ex-wife with typical movie star antics, and turning his 20-something daughter Sam – now his personal assistant – into a train wreck.

Riggan takes one final shot at artistic relevance by adapting Raymond Carver’s downbeat short story "What We Talk About When We Talk About Love" for Broadway, enlisting a troublesome troupe of players to mount a production so emotionally overwrought that it makes "A Streetcar Named Desire" look like a vaudeville skit. Hilarity ensues. And, among other things, Riggan is tortured by the incarnation of his "Birdman" character, who alternately mocks him for his foolish artistic ambitions, teases him with the ghost of missed opportunities, and eventually cajoles him to "take flight" and release his inner demons.

The anti-comic movie. Some portion of the comics community was intrigued by the premise of Birdman, particularly the notion of Keaton’s casting commenting on his real-life situation of having walked away from the original Batman role in the early 90s straight into career oblivion. The presence of Edward Norton (the second screen Hulk) and Emma Stone (Gwen Stacy in recent Spider-Man movies) seemed to emphasize the affinities even further.

In fact, Birdman is unremittingly hostile to comics and popular culture in all its forms. Both the character of Birdman and the over-the-top production values of comic movies are mocked as ridiculous; so is the socially-networked, pop-aware perspective of Riggan’s messed up millennial daughter Sam. A grotesque caricature of a theatre critic is also skewered for good measure, because all these things are enemies of serious art, don’t you see?

This isn’t just a subtext of Birdman. It is, in just about every way, the film’s entire reason for being.

Why we can’t have nice things. Subtlety isn’t one of director/co-writer González Iñárritu’s strong points, but in case you missed the point after two hours of having it hammered into you during the movie, the director gave an interview to Deadline Hollywood summing up his views.

"I think there’s nothing wrong with being fixated on superheroes when you are 7 years old, but I think there’s a disease in not growing up," he said. "The corporations and the hedge funds have a hold on Hollywood and they all want to make money on anything that signifies cinema. When you put $100 million and you get $800 million or $1 billion, it is very hard to convince people... Basically, the room to exhibit good nice films is over. These are taking the place of all those things.”

Later he adds, "Superheroes... just the word hero bothers me. What the f*** does that mean It’s a false, misleading conception, the superhero... Philosophically, I just don’t like them."

Welcoming the hate. González Iñárritu is of course entitled to his point of view. It’s one that even some hardcore comic fans might share if you put a gun to their head and asked "at what point do we have too much of a good thing?"

But it marks a change from the past 12-15 years when all the Hollywood Kool Kidz established their street cred by flaunting their love for comics culture. Remember Helen Miren showing up on stage at Comic-Con in a Harvey Pekar t-shirt?

Peer pressure seemed to be encouraging the film industry to embrace their inner geek, to rise above mockery and condescension and camp in their treatment of comics material. That intellectual climate among the industry’s elites created the necessary air cover to spend billions on movies featuring leading men (and the occasional woman) in masks and costumes.

Don’t tug on Superman’s cape. On Sunday night, those same Hollywood opinion-makers chose to recognize Birdman in the three most significant categories – Best Picture, Best Director and Best Screenplay. Considering the competition and Birdman’s slight dark-horse status in some of these categories (since it wasn’t, actually, a very good movie), how else to take this except a ringing endorsement of González Iñárritu’s brave stance in standing up to the tyranny of superhero fascism at the box office?

In the short run, the business interests that run the film industry don’t need to take note of rear guard elitism in the creative ranks. They’re just the hired help, after all.

However, it must be said that the grim pretentiousness of many superhero films is their Achilles heel: the thing that audiences are most likely to tire of when subjected to a continuous bombardment, as is scheduled for the next few years. And ridicule is a powerful weapon – at least when wielded by creators less ham-fisted in their approach than Alejandro González Iñárritu.

Superhero and comic book movies don’t have to be, or be seen as, great art to be successful. But it wouldn’t hurt for them not to be seen as the mortal enemy of great art. And that seems to be where Hollywood’s collective head is at the moment.

--Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.