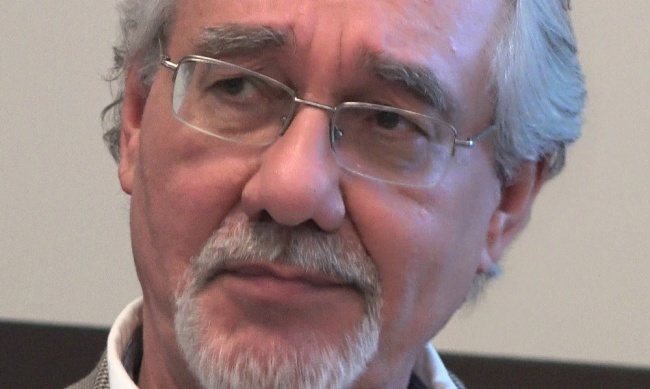

Artist, publisher, agent, comics historian and bon vivant Denis Kitchen hit the big 7-0 on August 27. Since his impact looms largest in my area of interest, the business side of comics, and because I’m lucky enough to count Denis as a personal friend, I’d like to take a moment to recognize his many contributions that have advanced the artform of comics, expanded its audience and distribution model, changed the relationship between creators and publishers, and helped both historical and contemporary comics achieve greater respect and visibility in the culture.

Denis Kitchen is probably best known as the founder and publisher of Kitchen Sink Press, one of the premier imprints of the underground comix movement of the 1960s. Kitchen Sink’s illustrious roster included R. Crumb, Justin Green, S. Clay Wilson, Trina Robbins, Jack “Jaxon” Jackson, and Kitchen himself, bringing their mind-expanding work to head shops across the country and dramatically expanding the creative boundaries of the artform in ways that ripple down to the present day.

Concurrently, the entrepreneurial Kitchen founded an entity known as the Krupp Syndicate to distribute underground strips to alternative newspapers around the country. Other arms of Krupp Comic Works were dedicated to merchandise, records, posters, trading cards and other paraphernalia, which increased the earning power of artists who were working on a shoestring. One of his more interesting efforts to broaden the audience (and increase the artists’ paychecks) for underground work was a series called Comix Book, published in conjunction with Marvel Comics (!) in 1974.

Kitchen Sink was distinguished from its peers in several important respects. First, Denis ran a tight ship. In a movement where good business practices like written contracts and clear expectations were disdained as bourgeois formalities, Kitchen always kept careful records and prided himself on fair dealings with his artists, printers and distributors. He chalks this up to the influence of Will Eisner, whom he first met at a fateful encounter at the 1971 New York Comic Art Convention that launched a business and personal relationship that would last decades.

Kitchen Sink brought Eisner’s classic Spirit back to comics in the early 1970s, then picked up reprinting the stories in magazine format after a stint in Warren publications. This was part of a second big difference that KSP had with the other undergrounds – a dedication to bringing the classic comics strips of the 1940s and 50s to a contemporary audience.

Thanks in part to Kitchen’s personal enthusiasm for creators like Al Capp, Ernie Bushmiller, Milton Caniff and Harvey Kurtzman (as well as Eisner, of course), fans in the 1970s and 80s could read Li’l Abner, Nancy, Steve Canyon and out-of-print Kurtzman work like The Jungle Book and Hey Look! in good, affordable editions, as well as new graphic novels from Eisner and others. By putting these out as trade editions, Kitchen helped raise public and retail awareness of the graphic novel format’s viability, which paved the way for comics’ march into bookstores in the 1990s. In today’s world of graphic novel bestsellers, ubiquitous archives and Artist Editions, that sounds like no big deal, but during a period where comics’ artistic (and commercial) status was still a matter of lively debate, it was a bold and risky move.

Finally, Kitchen Sink was the only underground press to successfully transition from the 1960s era to the modern age of independent comics publishing and retain its relevance. In the 1980s, KSP occupied a space between the artsy alternative work coming from Fantagraphics and Art Spiegelman’s RAW, and aspiring mainstream publishers like Pacific, Eclipse and Dark Horse. Kitchen Sink published early work from Charles Burns, Mark Schultz, Monte Beauchamp, Kate Worley, Reed Waller and many others, including Howard Cruse’s landmark Gay Comix in 1980. The company’s catalog from that era looks remarkably prescient and modern even 30 years after the fact.

In 1994, Kitchen Sink merged with Tundra, the ambitious but undisciplined publishing enterprise launched by Kevin Eastman. At first, the union brought some great work to market, including Dave McKean’s Cages, the first edition of Scott McCloud’s landmark Understanding Comics, and James O’Barr’s The Crow. But eventually financial issues drove the business under.

Denis Kitchen re-emerged as an artist’s agent and book packager, working with Eisner, the Kurtzman estate, Crumb and others to get their works into better editions and wider distribution, in partnership with literary agent Judy Hansen, and later book designer John Lind. He also authored several works of comics history including biographies of Kurtzman and Capp. In 2013, he joined Dark Horse as part of a joint venture to relaunch a Kitchen Sink books imprint.

Along the way, Kitchen found time to found the free speech advocacy group the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund to protect creators and retailers from harassment by overzealous government authorities.

All of Denis Kitchen’s activities in publishing, business, comics history and advocacy meant the world saw less of his oddly compelling artwork, which remains some of the best to emerge from the underground era. He says that at one point, he asked Harvey Kurtzman whether he should give up publishing to pursue more of his own work, and Kurtzman, to Denis’s surprise, advised him to stick with the business, saying there were plenty of artists, but not enough good people working on other side of the desk.

Denis Kitchen isn’t exactly an unheralded figure. He was inducted into the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame in 2015 and has a shelf full of awards to show for his long and successful career. But, as with Kirby, the generation that grew up with his work tends to take it for granted, and younger people know it only by reputation and influence, if at all. The diffuse nature of his endeavors, and the fact that he spent a lot of time behind the scenes on the business side, makes it harder to discern the pivotal role he played at almost every point in comics’ 50 year march from lightly-regarded juvenilia to serious art and literature.

The good news is that Denis is 70 years young and still buzzing with new ideas, new projects and new art. He’s seen his life’s work of getting great comics recognized as work of lasting cultural and artistic importance largely accomplished, and yet spending even a few minutes with him, you get the impression that there’s still plenty of great stuff yet to come.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.