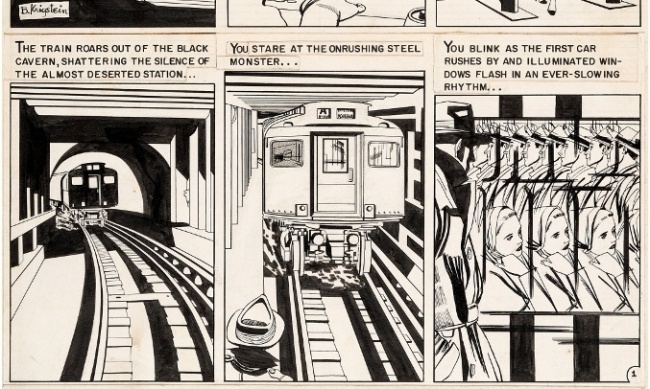

A Comic Art Masterpiece. As many ICv2 readers are likely aware, "Master Race," written by Al Feldstein and drawn by Bernie Krigstein, was first published in Impact #1 in April, 1955, one of the last classics of the EC era. The story was not only one of the first comics to address the issue of the Holocaust, but one of the very first creative works of any kind to deal forthrightly with the genocide perpetrated by the Nazis, according to We Spoke Out: Comics and the Holocaust, a valuable survey of the topic by Rafael Medoff, Neal Adams and Craig Yoe that came out recently.

That historical detail alone makes the story significant, but it’s Krigstein’s cinematic artwork that elevates "Master Race" to one of the all-time classics of American comics. Krigstein squeezes dozens of innovative storytelling techniques into the brief vignette, laying a template for future work by creators such as Jim Steranko, Frank Miller, Dave Gibbons and just about anyone else who has pushed the formal boundaries of the medium.

To paraphrase Indiana Jones, that art belongs in a museum. Certainly if any piece of comic art does, it’s that story. And yet, when the lot came up for auction, it seemed destined to vanish into a private collection, like most of the 20th century masterpieces of original art, continuing a market dynamic that makes it difficult to mount large-scale museum shows now that comic art is finally getting its due as being worthy of public exhibition.

Behind the Velvet Rope. Earlier this year, I wrote about the Marvel Universe of Super Heroes exhibit at Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture (MoPOP), mounted by SC Exhibitions and Marvel, and curated by a team of scholars led by Dr. Benjamin Saunders from the University of Oregon. That show features a remarkably high number of iconic pieces from the Golden Age to the present. All but one – a page from the first Spider-Man story from Amazing Fantasy #15, on loan from the Library of Congress – come from private collections.

That’s not the norm in the world of fine art museums, where most acknowledged masterpieces are owned by institutions. Other museums, galleries, libraries, universities and family trusts have been loaning out their work for centuries. The owners may appreciate them for their cultural value and their financial worth, but they don’t have the same attachment as a first-generation collector who has tracked down a grail item or someone who has acquired a piece that has personal significance to them.

Moreover, many pieces in the fine art world have a known provenance. That is, museums know where to find them when they want to curate them for a special exhibit. It’s not necessarily easy to put together a Picasso retrospective or a Rococo Masters show, but curators know how to do it, who to call to find the pieces they want, and established practices to follow when dealing with loaning institutions.

It’s a Long Way to the Ivory Tower. With comic art, none of that infrastructure exists. We’ve all heard stories of how comic art was disdained and discarded by publishers or given away to fans writing letters, before it started becoming collectible in the late 1960s. Artists themselves rarely thought much about their originals, considering them artifacts of a production process or pieces of disposable commercial art.

Even after the original art market began to expand and a few artists had successful museum or gallery shows, no institution systematically invested in original comic art in the 20th century. Consequently, just about every important piece is in private hands, gone, or stuck in a warehouse somewhere.

That has big consequences for presentation of comic art in cultural forums. The team putting together a show like the Marvel Universe of Super Heroes has to find out who owned particular pieces, then negotiate with private collectors to get them to part with their precious masterpieces on terms that might be business-as-usual for museums, but can be intimidating to ordinary art owners.

Putting together a permanent collection, as San Diego Comic-Con is attempting to do with its new facility in Balboa Park, will be even more daunting (at least until first-owner collections start passing to heirs and estates), because buying important pieces on the open market is quickly becoming cost-prohibitive for institutions that don’t have very deep pockets, expertise and connections.

A Boon to the Art World. That brings us back to the "Master Race" story and its buyer, Philippe Boon on behalf of his Belgium-based Boon Foundation for Narrative Graphic Arts. According to a story in the New York Times about the sale:

"Philippe Boon is 'one of the main collectors of original comic artworks as well as objects, statutes, illustrations and paintings,' said Daniel Spindler, the vice president of the foundation, who noted that Boon has one of the broadest collections of this kind of work in Europe. Boon wants to 'open the richness of the collection to public eyes,' Spindler said.

"The organization acquired 'Master Race' for its historical significance and for Krigstein’s critically acclaimed presentation of the suspenseful story. 'We want to explore the richness and the variety of storytelling, not only for comics, but also for other graphic arts,' Spindler said.

The foundation is designing an exhibition space in central Brussels that will also include video games and films. 'We don't want it to look like a normal museum,' Spindler said. 'What we show will always be original pieces. We believe you feel something special when you are in the presence of these kinds of works, more so than a reproduction.'"

That's right: this was an institutional acquisition, intended for museum display. That's the good news. The bad news is, this treasure of American comic art will live in a European museum, acquired by a Belgian collector who was willing to back up his commitment to exhibiting it with a hefty bid in a public auction.

Perhaps someday it will come back to these shores on loan, because at least now, American curators will know where to find it.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

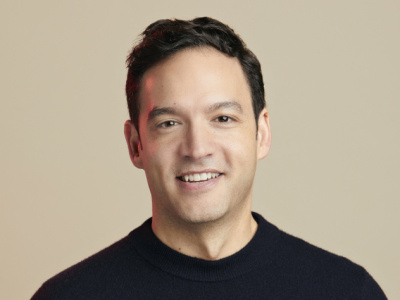

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.