As every ICv2 reader knows by now, graphic novel and trade book sales are now the biggest part of the US comics market by revenue (see "Comics and Graphic Novel Sales Top $1.2 Billion in 2019"), so it makes sense to look closely at what’s going on in that segment of the business for trends about consumer preferences. With that in mind, I took a look at the BookScan numbers posted in the ICv2 Pro section (see "NPD BookScan Top 20 GNs Index") for sales over the summer to reflect on some current trends and take stock of a few remaining blind spots.

Comfort Foods. Unsurprisingly, consumers this year are clinging tightly to the tried and true. Just as some of us are binge-watching old favorites and not straying too far from home (either out of prudence or necessity), we’re also buying or rebuying familiar titles and brands in big numbers.

For example, the August "Superhero" category top 15 includes eight stone cold classics: Batman: The Long Halloween, Sandman Volume 1: Preludes and Nocturnes, V for Vendetta, Batman: Year One, Batman: The Killing Joke, and two editions of Watchmen, which clearly benefited from the award-winning though tangentially-related HBO series (see "August 2020 NPD BookScan – Top Author, Manga, and Superhero Graphic Novels"). Fine selections all, but most of these books are over 30 years old. Yes, they’re being repackaged in nice new formats, and I guess there’s always someone out there who hasn’t read these yet, but really? More than half the top 15 in high summer 2020?

The Manga charts at this point belong to VIZ Media, which publishes all the titles in the top 20, dominated by My Hero Academia. Unsurprisingly, it’s a brand-driven list tied closely to popular media properties, COVID or not.

How about the independent titles (ICv2’s "Author" category), where you might think readers would take a flier on something a little more exotic? It’s a little more diverse, but still a case where familiarity wins the day. In August, the month following the passing of civil rights icon John Lewis, readers scarfed up copies of Top Shelf’s best-selling March trilogy, with both the individual editions and the slipcased set making it into the top 15. The rest of the list consists of Umbrella Academy and Old Guard collections tied to the streaming series adaptations, along with various installments of Adventure Zone, a couple of other celebrity author titles (George Takei’s The Called Us Enemy and a new adaption of the classic To Kill a Mockingbird), and, somewhat randomly, Alison Bechdel’s 2005 classic Fun Home.

Nothing against these worthy titles; it’s just unfortunate to see such a power curve in action in a category where a healthier market, literally and figuratively, might propel some new voices and original ideas further into the culture.

Graphic Novel Casual Dining. When you look at the more important side of the graphic novel sales charts, the kids list, you see some of the same dynamics at work, with a new wrinkle. Comics for younger readers are the 800-pound gorilla these days, not just in the comics publishing world, but in the publishing world writ large. Dav Pilkey, Raina Telgemeier and the other superstars of the younger set are in the absolute elite levels of the American book sales world, moving millions of copies.

A couple of individual talents may have lit the way in terms of the market possibilities for kids books, but publishers looking to follow them into the hearts and wallets of Gen Z seem disinclined to leave anything to chance now that they know what sells. Why would they? You don’t see Applebees or Denny’s giving their chefs much room to embroider on the menu.

But wait, I hear you saying – the range of voices, themes and characters represented in these books has never been more diverse. Publishers are taking more pains to address issues of gender and gender identity, race and ethnicity, body type and ability, and neurodiversity so that all kids can see themselves in the story.

That’s true, and very laudable. However, when you crack the covers of those books, you’ll see a similar formula being executed in both story and art. In terms of story, that’s understandable: kids’ lit isn’t really the place to radically experiment with plot structures, character arcs and expected story beats, especially if you are already expanding the palette in terms of themes and characters - and trying to sell six figures’ worth of books.

What’s unfortunate, at least to my eye and taste, is the homogenization of the art style once you get beyond superficialities. So many of these young reader books look the same, and fall back into some tired cliches of visual storytelling. Backgrounds are simplified, color palettes flattened out, staging consists of long scenes of talking heads. Even in cases where the illustrations are well-crafted, it’s rare to find examples of the drawings carrying the narrative forward.

Part of that is probably the calculation that giving the artist(s) a couple of extra months to make the artwork pretty won’t sell any more books. If these books sell on the strength of the familiar series, the author, the publisher imprint and, to some extent, the thematic or identity-oriented elements of the story, the cartooning quality isn’t the place to invest scarce resources or hold up the production timeline.

For each individual book, you can overlook the fact that it’s not great as comics, especially if it is successful in other ways and the art is "good enough." They can’t all be Nimona or Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me, after all. At scale, though, the house style of young reader comics starts to get oppressive, and Sturgeon’s Law looms large.

For art snobs like me, the hope is that the generation raised on these books will eventually demand more from their graphic literature as they hit their later teens and young adulthood, rather than come to the conclusion that middle-of-the-road comics are their comfort food, the ones they’ll buy over and over again in different formats and editions when the outside world starts feeling overwhelming.

Good Read for Grown-Ups. Luckily, the fat slice of the commercial business, whether it’s comfort-food superheroes or casual dining kids graphic novels, isn’t the only game in town. There are still some great books out there for adventurous readers who want something different, even if the market doesn’t make it easy to find them.

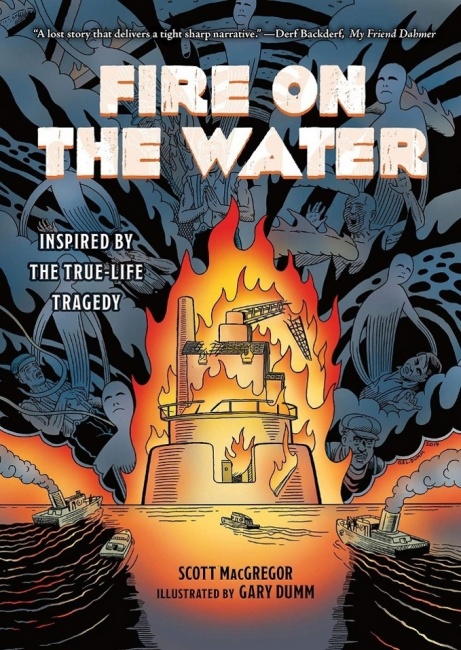

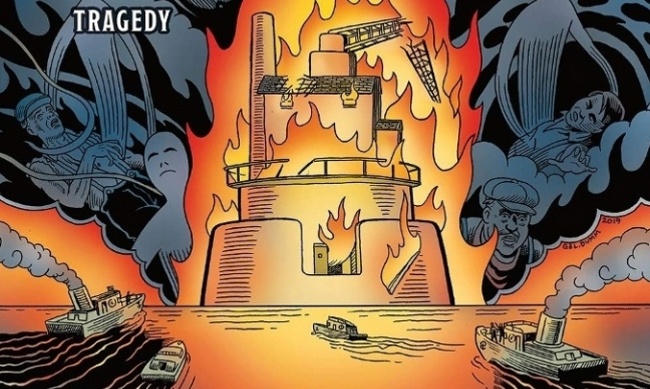

One that crossed my radar recently was Fire on the Water (Abrams ComicArts), the fictionalized account of a disaster on a pumping station near Cleveland, Ohio in the early 20th century, written by Scott MacGregor and drawn by Gary Dumm. This handsome volume came out earlier this year (see "Abrams ComicArts 2020 Spring List"), but got caught in the COVID crunch; I haven’t seen it reviewed much. But frankly, even in a normal market, it probably would have been a hard sell because it works against all the trends in the industry right now.

Fire on the Water has the arc and structure of an all-ages story, with some clearly defined good guys and bad guys. However, most of them are adults with some adult motives, and that’s a definite no-no if you’re trying to sell to kids these days. It’s set in an era where ethnic stereotypes prevailed, so some of the historically-accurate social detail and dialogue might read as "problematic" to sensitive contemporary readers, despite being explicitly anti-racist in its overall intent.

There’s a lot of texture and detail to MacGregor’s story, which would be a good challenge for a precocious middle grade reader, but the story itself is about the hardscrabble reality of working class life, and thus probably resonates more with readers with life experience.

Artist Gary Dumm is probably best known as one of Harvey Pekar’s graphic collaborators on American Splendor. His art style is workmanlike in the best sense in that he prioritizes pace, staging, storytelling and verisimilitude. Though his line is simple and straightforward with a limited expressive range, he doesn’t skimp on backgrounds and he doesn’t shy away from ambitious and dramatic depiction of events when the story calls for it. He also fought through a lot of personal adversity to get this book done, and the pride shows.

In a perfect world, Fire on the Water would be a book with broad cross-generational appeal: approachable by younger or less experienced readers interested in a good reality-based story, while also offering something for graphic novel connoisseurs who appreciate veteran craftsmanship and the ambition to take on more wide-ranging themes and topics.

Instead, it risks missing both audiences because it doesn’t adhere to the familiar conventions of either successful market quadrant, and it’s not really arty enough to call attention to itself on the strength of sheer virtuosity, a la My Favorite Thing is Monsters.

The graphic novel marketplace has come a long way. If it can find commercial space for non-formulaic works like Fire on the Water, it will have even more to be proud of.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

Posted by Rob Salkowitz on September 28, 2020 @ 7:54 pm CT

MORE COMICS

At AnimeNYC

August 22, 2025

The winners of the 2025 American Manga Awards, organized by AnimeNYC owner LeftField Media and Japan Society, were announced in a ceremony at AnimeNYC in New York on August 21.

From Marvel Comics

August 22, 2025

This October, Marvel Comics celebrates the release of TRON: Ares with new variant covers.

MORE COLUMNS

Column by Jeffrey Dohm-Sanchez

August 21, 2025

ICv2 Managing Editor Jeffrey Dohm-Sanchez continues to take a look at some of the issues revolving around Universes Beyond products.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

August 19, 2025

For Horror Week, columnist Rob Salkowitz asks whether the horror boom can help get us through a moment full of woe and dread.