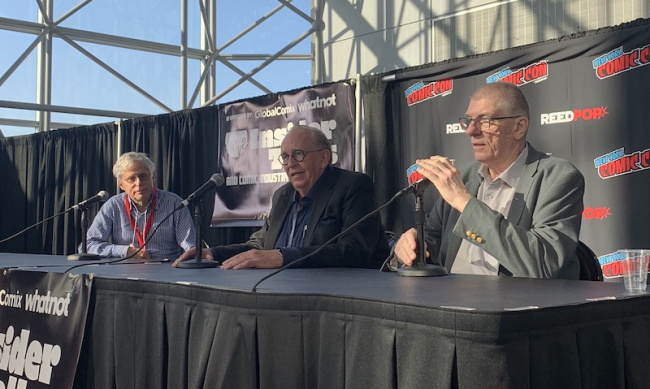

The story begins in 1972, when Phil Seuling started Sea Gate, the first direct comics distributor, and Levitz, at age 16, started working as a freelancer for DC Comics, where he would eventually become President. Levitz also started working for Sea Gate: “Phil was a wonderful idea guy, enormously passionate, and probably allergic to every form of paperwork on Earth,” he said, so he spent a few days a week opening and dealing with the mail. Then one day, Sea Gate came up at the DC office. “Sol Harrison, who was the VP of Operations, comes up and says ‘Phil Seuling is pitching us on this idea of selling direct to comic shops. Do you think that’s a good idea?’” Levitz thought it was.

A few years later, in 1978, Shooter became Editor-in-Chief of Marvel. As he reviewed the print orders, he noticed a small quantity of comics allotted to something called Sea Gate. Puzzled, he asked Director of Circulation Ed Shukin what that was. “Ed got up and closed the door, and he said, ‘Look, we're selling comics to this guy Phil Seuling and he's distributing to comic shops,’” Shooter remembered. “He said, ‘Don’t tell anyone.’” As it turned out, the exclusive deal with Seuling was illegal, so Marvel broadened it. “We decided to publish trade terms and open up to anyone who could meet the minimums,” Shooter said. “Overnight, we had 18 distributors.” Over the next 15 years, that group had narrowed down to two, Capital City Distribution and Diamond Comic Distributors.

While comics were still sold on newsstands in that era, the newsstand and comic shop audiences were diverging. Shooter kept an eye on the Direct Market and noticed that X-Men comics were selling better than other titles. “Clearly, the ones that we thought were the best were selling the best,” he said. “In other words, the readers have good taste.”

The comic shop audience clearly had different tastes than the casual readers who picked up comics on the newsstand. In the late 1970s, for example, Jack Kirby’s comics were not selling well on newsstands. “I think people looked at them and thought they looked old fashioned,” said Shooter, “Once the Direct Market got going (and this is the middle of 1978), all of a sudden Jack Kirby's comics in the Direct Market were selling 30,000 copies. It opened the market for all kinds of things that might not [appeal] to the general public.” So Marvel began to support the retailers. Direct Sales Manager Carol Kalish started a program to help them get cash registers, and Marvel published its first Direct Market-only comic, Dazzler #1, which sold 428,000 copies. “We really saw the potential, and we tried to do something about it,” he said.

“I think Marvel had a structural advantage, in that they were one of the bread-and-butter pieces of their parent corporation,” Levitz said. DC’s strategy was to do its best to match what Marvel was doing and to compete on credit and financial terms. “When you’re the underdog, you try to offer a better deal than the big dog,” he said.

The shift to the Direct Market changed the comics themselves in many ways. DC changed its product mix. “We said, look, House of Mystery is selling fine on the newsstand,” Levitz said. “It probably is selling to 10- to 12-year-old girls mostly, but that's not going to be our future in three years. So let's get House of Mystery out of the way and free up the editors and the writers and artists to be able to do something that might be a better comic for the Direct Market.”

In a major advance for creators, Marvel began paying royalties. “I had to go to the Board of Directors for that,” Shooter said. “Stan [Lee] came with me. I was pitching, and he was saying ‘He’s right! He’s right!’ But we got it done.” The amount Marvel paid out in royalties the first year was more than double what they projected, “That means our sales skyrocketed,” Shooter said.

Creators who got royalties were more invested in their work, so they stayed on series longer and brought their best ideas to the table. “Look at Marvel with X-Men,” Levitz said. “Chris Claremont had been writing that for probably four or five years by the time the royalties came on, which was a very long time for a writer to stay. If he hadn't had royalties, there's a pretty good probability he would have said, ‘Let me try Spider-Man, let me try Avengers, something else.’ But because there were royalties, and suddenly he was making bags of money, justifiably, rightly, he was able to stay on that for 17 years.”

“In the same way,” Levitz continued, “Frank Miller does a run on Daredevil and then gets passionate about it and then tries Ronin as a project. I think Milton had a warehouse full of Ronin for the next 10 years.”

“I heard from Bud Plant, he said he was rolling them up and selling them as cordwood,” Shooter said drily.

“But it was a step forward for what we were trying to do in the market,” Levitz continued. “Frank saw that, did a few more Daredevil things, and then came back to do Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, which was one of the transformative books for the business.”

Creators didn’t just get royalties, they got cover credits, because readers followed individual writers and artists. Marvel and DC improved their paper and print quality, because comic shop customers were willing to pay more for better production values. “We thought we were selling to 6- to 12-year-olds,” Levitz said. “Now suddenly you had to be old enough to get to a comic shop. So we were selling to 16- to 25-year-olds. That changes what kinds of stories you can do, what kind of material, what kind of money they have in their wallet that you can liberate from them if you can put the right thing in front of them every week. So it was fundamentally a different business.”

“The Direct Market saved ongoing comics publication,” Levitz said. “The medium of comics would have survived, newspaper comics, things like that. But what we did with the Direct Market and the things we did to build and make it a healthy business enabled comics to survive and thrive for another generation.”

For more on the history of the Direct Market, see "Direct Market 50th Anniversary."