Companies are trying, with varying levels of success, to accommodate the expectations of a broader audience. That includes commitments to address offensive or insensitive representations of characters, offer a wider range of subject matter, and bring in more ethnically and gender diverse creators.

Critical differences. A new generation of fans, bloggers and critics is holding the industry accountable to its inclusive rhetoric. Rather than focusing mainly on aesthetic and continuity concerns, they are more likely to view comics culture through the lens of identity politics. Outrage frequently ensues.

To an outsider, this makes comics look like a minefield of political correctness, with the pro-diversity, “check your privilege” crowd lined up against “traditional-minded fans” who distrust changes to established characters and stories to accommodate contemporary standards. In other words, it looks a lot like other aspects of our divisive culture and politics – a perception encouraged by click-through media that recognizes that a good “red vs. blue” fight is great for driving traffic (see “The New Politics of Fandom”).

Generating heat… and light. In fact, the P.C. critics are performing a useful service by broadening the conversation beyond the narrow boundaries of fandom. Sites like The Mary Sue focus relentlessly on issues of gender diversity and representation, championing authentic work and calling out unexamined (or, perhaps, strategic) sexism. Last month, the blog Graphic Policy highlighted the problematic representation of transgender people in a recent issue of Airboy, eliciting a thoughtful response from writer James Robinson. Black Girl Nerds is a voice for the vastly underserved readership of women of color.

One need not agree with their critical take on every issue to recognize the value these perspectives bring to an industry trying desperately to expand its audience, while still run largely by older white guys with an imperfect understanding of the motivations and attitudes of young, female and minority readers.

They also open the minds of readers. I’m an old white guy myself and have blind spots a mile wide. I can’t singlehandedly change the social constructs that influence my perceptions, but I can try to listen harder to the concerns of people who face challenges I can’t really conceive of.

Is it getting chilly in here? The increased attention to diversity and examination of unspoken cultural assumptions is largely a good thing for fandom, but it raises some red flags when critical sites find material so objectionable that they issue righteous judgments that the books should be “pulled from the shelves” or “never should have been made.” That just activates knee-jerk opposition from people convinced that diversity is just another word for Stalinism.

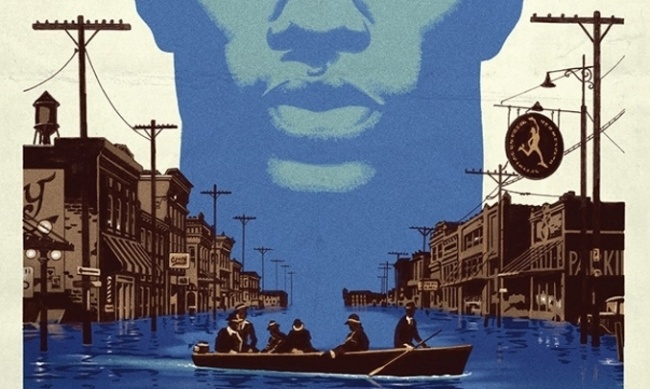

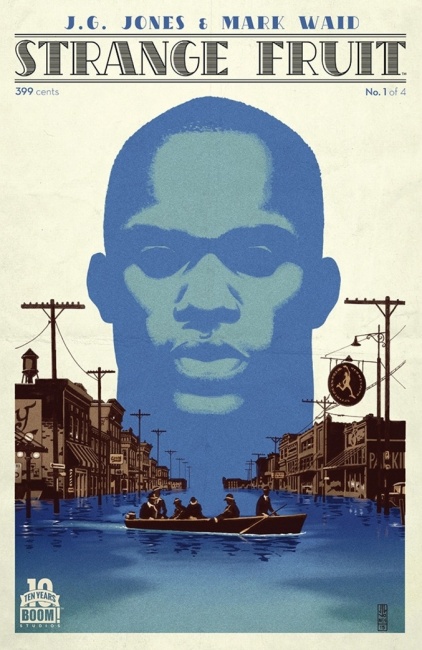

The most recent example of this is the discussion around Strange Fruit (BOOM! Studios), a series by Mark Waid and J.G. Jones set in the segregated South featuring a mixed race cast, including a black alien super-being who’s about to cause some trouble. Waid, who grew up in the South, knows his business; the story features some complex observations about race and class, and Jones’ detailed painted art strives for realism at every turn.Please don’t call it a lynch mob. In July, the book came under fire from critic J. A. Micheline at the site Women Write About Comics. In a long review thoroughly supported by aesthetic and historical examples, Micheline makes the case why a comic set in such a racially-charged context simply can’t be done right by white creators, regardless of their skill or motivations.

“This comic should never have been made,” she writes, “because there is too long a history of white people writing stories about racism and blackness, too long a history of white people shaping these tales to their own purposes, too long a history of white people writing about what they genuinely cannot understand.”

Micheline has observations about the story and the book, but she is really calling out the industry on institutional point of view that seeks to keep white audiences comfortable at all costs and is, at best, insensitive to the concerns of minority audiences. Waid and Jones may be telling the best story they can, informed by their knowledge of history, Southern white culture, and general human nature, but that is no substitute for having a creator with a personal understanding of racism as experienced by its victims. Is she wrong about that? That’s surely a discussion worth having.

More speech, not less. The problem is that some readers don’t get the concept of institutional racism, and so Micheline’s cogent point was reduced, in online argumentation, to crude assertions that Strange Fruit is a racist book, Waid and Jones are racists, or (ironically) that Micheline herself is a racist. That is not only grossly unfair to both the creators and the critic, but also a surefire way to shut down intelligent debate.

Unfortunately, arguments around inclusiveness, gender and race in the context of art and individual creativity lend themselves to over-simplification. The frustrations expressed by critics like Micheline and Brett Schenker (who led the charge on the Airboy transphobia matter) over clueless industry approaches to diversity can look like calls for censorship, even when they are technically just calls for readers to ignore the books or for publishers to wise up.

To me, the main takeaway of these critiques is that we need more creators from diverse backgrounds making comics, not necessarily that books that don’t deal perfectly with issues of diversity should not be published or sold. Yes, certain books are “problematic.” If you take comics seriously enough to discuss them as art, then it’s useful to recognize that some art isn’t “safe,” and some creators deliberately take stories in directions that make readers uncomfortable.

But perhaps that’s just my privilege talking.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture, and consults with businesses interested in engaging with fandom and conventions.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.