Sign of the times? The state of California, having apparently solved all of its other more pressing problems, decided to address this burning crisis with new legislation. Governor Jerry Brown signed AB1570 Collectibles: Sale of Autographed Memorabilia into law on September 9, and it is scheduled to go into effect on January 1, 2017.

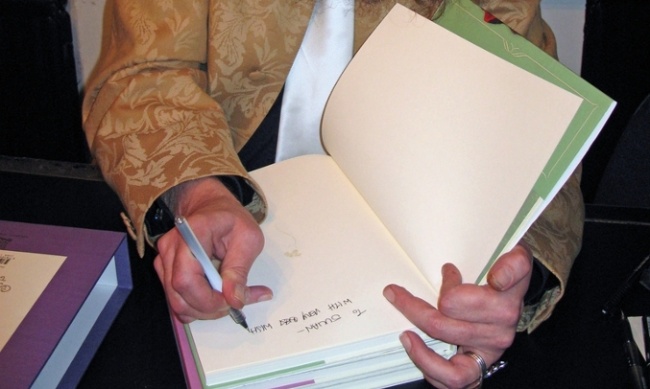

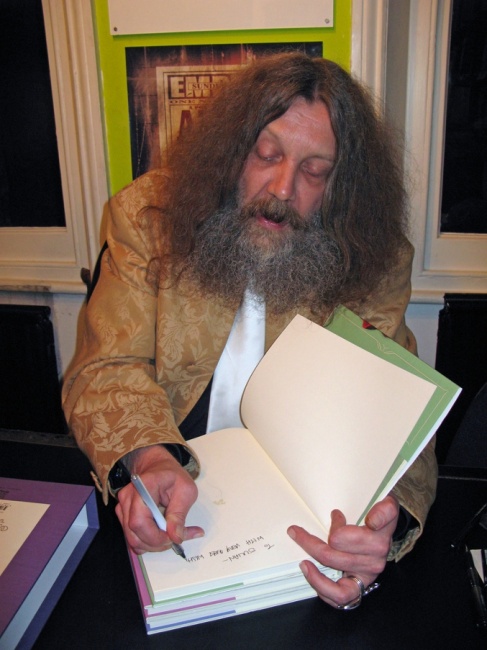

The law requires anyone who deals in autographed material, whether a collectibles dealer or bookstore hosting an author signing, to provide certificates of authenticity (COA) for any signed item sold for $5 or more. The specifications for the COA are laid out in great detail in the law, and include nine different criteria for identifying an item’s provenance. Sellers who do not provide a COA with qualifying autographed items may, according to the law, “be reported to law enforcement, and be held liable for a civil penalty of 10 times the amount of damages” plus court costs.

This certainly provides the buyer with a high degree of certainty that the item they are buying is authentic. Unfortunately, legislation like this always seems to come with a raft of unintended consequences.

Sellers are on the hook. In a letter to his state legislator, California-based retailer Brian Hibbs observed that small businesses like comic stores would be exposed to an enormous amount of financial risk for failure to meet the stringent documentation requirements, and this might discourage them from hosting signing events that benefit creators, literacy, and awareness of comics. He also points to the threat of “professional frivolous litigation to shake down legitimate California businesses” because of the huge financial incentives of bringing successful actions under the law.

There’s another downside as well. Some buyers of autographed items will eventually become sellers. In that case, the seller must furnish their name and address as part of a COA issued to the next buyer, who will then be entitled to pursue legal remedies if the documentation is inadequate.

This doesn’t just apply to second-hand items. If you own signed artwork or collectibles that incidentally include a signature, or even if you are selling something that you personally witnessed being signed but don’t have evidence to back it up, you are still required to authenticate it before it is sold if one of the parties to the sale is a resident of California, or if the sale takes place in the Golden State (perhaps at a convention?).

Meanwhile, the state and federal government are ignoring a much larger issue in the autograph economy: the huge volume of untaxed cash transactions taking place at conventions.

A couple of weeks ago, the Hollywood Reporter posted a sensational story about the convention economy describing how stars take home “garbage bags full of $20s” from appearances and autograph sessions. How much of that income gets reported?

Taxing garbage-bag income. It’s not just a rhetorical question. If a convention guarantees a celebrity guest a minimum appearance fee, they only issue payment for the difference between what the celebrity was promised and what they received from autograph sales. So if a star was promised a $75K minimum and made $50K in cash from autographs during the show, the only tax-reportable documentation of that transaction is a check for $25K from the convention.

Some C- and D-listers with their own tables or in Artist Alley don’t receive minimums, travel to the shows at their own expense, and operate exclusively on a cash basis. Obviously it’s worth their while, since they keep coming back. Have you ever gotten a receipt for one of these transactions?

Failing to report cash income can get you in big trouble, whether you are a waiter, a golf caddy or a 90s TV actor moonlighting at a fan con. You might ask, what kind of agent would put the talent at risk over those kinds of financial dealings? Answer: the kind of agent who has no responsibility for the celebrity’s main career, but is only an intermediary who arranges bookings for conventions and events – that is, the predominant agent-relationship in the con industry today.

So how much taxable revenue is changing hands under the table at conventions? And as a practical matter, are autographs services (e.g., taxable as income) or goods (taxable via the sales tax)?

Seems like a good issue for a state legislature to take up, since they are suddenly so interested in this subject. I’d start a petition drive, but I’m afraid I’d have trouble authenticating all those signatures.

Addendum: In this piece, I gave the mistaken impression that individual sellers would be subject to the regulations of this law if they sold or re-sold their signed collectibles to other individuals. The law only applies to professional dealers, defined in the legislation as “a person who is principally in the business of selling or offering for sale collectibles… or a person who by his or her occupation holds himself or herself out as having knowledge or skill peculiar to collectibles.” However, individuals may still be liable if they are selling via consignment or through an auction house (not eBay). Efforts are underway on behalf of book and comic sellers to amend and clarify the legislation.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.