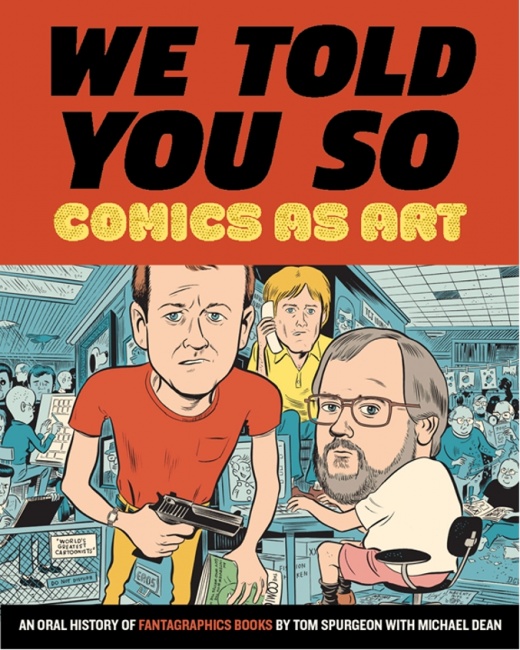

The recollections of Groth and his late partner, co-publisher Kim Thompson, are the most prominently represented, but everyone from R. Crumb and Daniel Clowes to one-time Fantagraphics PR man and current Fantagraphics store proprietor Larry Reid are heard from. The story unfolds year by year, decade by decade, in a series of intimate anecdotes and tall tales.

Spurgeon’s deft assembly of the stories and interviews keeps the pages turning. I literally could not put this book down, lugging it around the house so I could read snippets here and there between other activities. As someone who got into fandom in the 1970s, started reading The Comics Journal in the early 80s, hit college just in time for Love and Rockets, then moved out to Seattle in 1989 shortly after Fantagraphics arrived from California, there were times when I felt like this book was written just for me. Not only did I recall the controversies and milestones from when they took place, but I could picture many of the scenes of Seattle during the 1990s and 00s, and knew enough of the contributors personally that I could hear their interviews in their voices.

Anyone with similar background who remembers the battles waged by Fantagraphics over the past 40 years of the comics business – which I suspect covers a lot of the people reading this column in ICv2 – will find We Told You So to be a compulsive, though occasionally frustrating read. The problem is, I think the book might be intended for a slightly wider audience. And that could be a challenge.

Worm’s eye view. Like its subject, We Told You So makes few if any concessions to the unlearned and unsophisticated. If you want to know how much fun it was to hang out with Los Bros at conventions in the 1980s, or what Peter Bagge thinks about how his work became part of 90s “grunge” culture, you will find page after page of juicy inside info. If you want to know what makes Love and Rockets aesthetically interesting or significant as literature, or don’t actually know who Richard Sala is, you might get the feeling of being in one of those stores where if you have to ask the price, you can’t afford it anyway.

The same caveats apply to the book’s version of industry history, which feels a little like that famous New Yorker cover that shows the world tapering off once you cross the Hudson (or, in this case, Seattle’s Lake Washington). If you are looking for the broader story of comics-as-art beyond what Fantagraphics contributed, an objective look at the issues and controversies that The Comics Journal either instigated or covered, or the voices of people discussed in the book who were never associated with the company, this isn’t the right place.

For example, at one point when discussing a lawsuit that writer Michael Fleischer brought against Groth and the Comics Journal in the early 1980s over remarks made about his work in an interview with Harlan Ellison, several of the people interviewed wonder why Fleischer interpreted Ellison’s comments – intended as praise, and later explained as such – as defamation. Why indeed? Perhaps, 30 years later, this is an answerable question. Has Fleischer ever said? We don’t know from this account, because We Told You So is a book about Fantagraphics, not about Michael Fleischer.

There are many situations like this, where it is assumed that the reader already knows the details of old feuds and only cares about Fantagraphics’ perspective. If that’s you, run out and get the book. If not, you may need some supplemental info to appreciate it fully.

Critical oversight. In one odd way, this 700-page volume celebrating Fantagraphics’ accomplishments shortchanges its subject’s importance. It might have been nice to get more of a sampling of the critical material, which arguably advanced the “comics as art” project nearly as much as the work that Fantagraphics published.

The Comics Journal was not only a troublemaker, a documenter of creators’ views through their long interviews, and a source of quality reporting about the industry; it was also a pioneer in bringing serious voices to comics criticism. Starting as early as the late 70s, TCJ brought us R.C. Harvey’s closely-observed formalism, Heidi MacDonald’s voice-in-the-wilderness feminism, Bart Beaty’s academic scholarship, Jeet Heer’s broad cultural and political perspective, and others who brought rigor to comics studies at a time when intelligent discussion of the medium was practically non-existent. Those folks are tremendously important figures in the history and present-day of comics studies, criticism, and journalism, and the four mentioned above, put together, rate less space than humorous anecdotes about an anonymous intern from the mid-1990s.

Fascinating and frustrating, just like its subject. Taken together, these are minor quibbles with a beautifully-designed and well-edited volume that is, for the most part, as honest and unsparing when discussing Fantagraphics’ missteps and rough edges as it is celebrating its triumphs.

Love Fantagraphics or hate it, it’s worth celebrating that the company has survived for 40 years as an independent publisher with an uncompromising dedication to its principles. We Told You So offers insight into how the company rose, how it operates, and how it survived to see its belief in the potential of comics as art largely realized. It also demonstrates, by anecdote and example, the audience-limiting risks of those same principles and approaches.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.