Confessions of a Comic Book Guy is a weekly column by Steve Bennett of Super-Fly Comics and Games in Yellow Springs, Ohio. This week, Bennett looks at death in the comics, and how the lessons show the way to making great comics.

Marvel Editor in Chief Teases More Permanent Comics Deaths reveals that while at an unspecified Swedish comic book convention Marvel Editor-in-Chief C.B. Cebulski promised, "…to pump the brakes a bit when it comes to killing off characters," he’s also quoted as saying "I don't want death to be used to boost sales or to use as a shock value...,” and if “we choose to do it now, we're going to add a little more weight and permanence to the situation." I certainly hope that this is the case because as Avengers: Endgame made abundantly evident, Marvel Comics simply can’t do death as well as the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

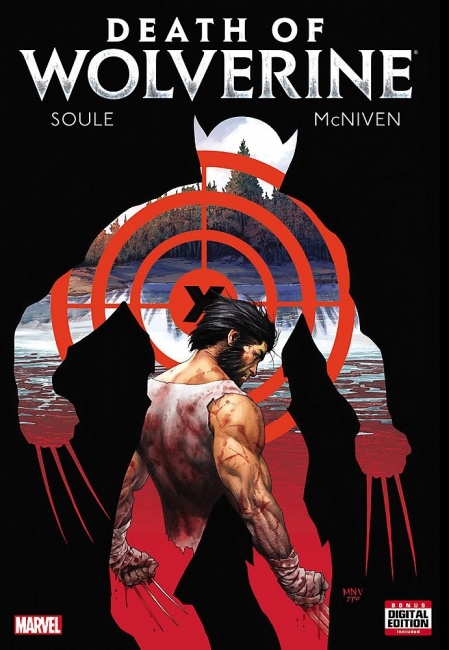

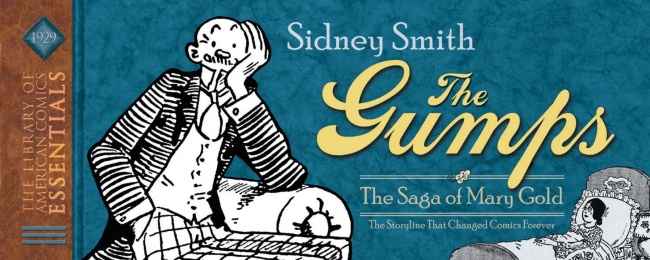

The Death of Wolverine may have gotten Marvel some free press and sold some comics but, ultimately nobody cared, while when Tony Stark died in Avengers: Endgame, people all over the world cried. Once comics used to have this kind of impact on people; take Sydney Smith’s The Gumps, a daily newspaper strip created in 1917 about the middle-class family of Andy Gump* which was a mix of drama, adventure, and comedy. The Gumps wasn’t just popular, it was a cultural phenomenon equivalent to Peanuts or The Simpsons and it made Smith a multi-millionaire.

It also made history, being the first comic strip to kill one of its major characters. When its ingenue Mary Gold finally died after a long illness, the news made headlines, Americans unironically mourned as if she were a real person, and the Chicago Tribute Syndicate had to hire extra staff to deal with the deluge of calls and letters of condolence. Hogan's Alley magazine has called the sequence “One of the Ten Biggest Events in Comics History” and in 2013 it was collected as part of IDW’s Library Of American Comics series; LOAC Essentials Volume 2: The Gumps - The Saga of Mary Gold.

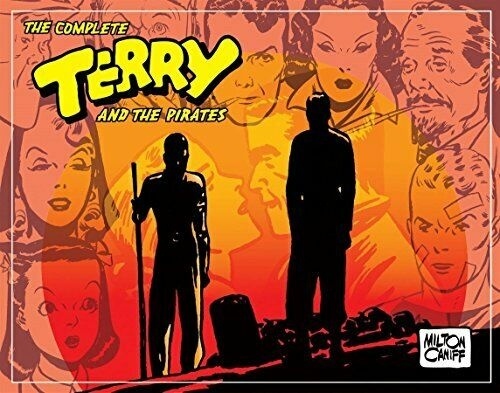

This sort of thing still wasn't common 12 years later in 1941when in Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates’ Raven Sherman, an American heiress doing missionary work in China died after being thrown from a moving car in Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates. Readers were devastated and Caniff was bombarded with letters, some sharing their shock and sadness, while others were death threats. But more significant than the immediate reaction was the lasting impact the story had; Caniff’s fans never forgot it and for decades after the artist received letters from them on the anniversary of Raven’s death. It’s rightly considered one of the best stories ever told in comic strip form, and if you haven’t read it, you really should.

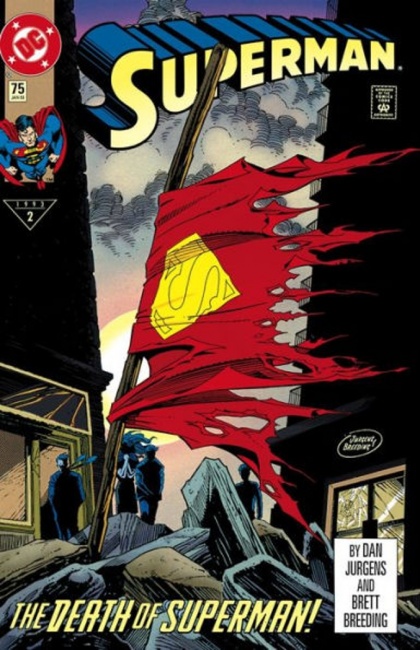

While that sort of thing is now a lot more common, see 12 Memorable newspaper comic-strip deaths for other examples, they’ve also lost a lot of their significance. Partially because comic strips no longer carry the cultural importance they once did, but also to blame is the way death gets handled in superhero comics. In 1992 The Death of Superman was indisputably a cultural event which received an extraordinary amount of mainstream attention; it was even parodied on Saturday Night Live. It was also a massive financial success, according to Wikipedia, Superman #75, the issue featuring his death, made "a total of US$30 million during its first day on sale and ultimately sold more than six million copies."

It was an immediate sellout and while a lot of people did buy it thinking would become a collector's item, just as many were former readers and people who had never read comics before. And the story itself unquestionably did have a lot of effects. I know it's hard to believe today but while hardcore fans naturally assumed this was only temporary, a lot of people really did believe Superman was going to stay dead. And while there was a brief spike in sales of comics, there was also an immediate decline; clearly what they read didn’t make all those new readers come back for more.

Its ultimate legacy is that it made comic book characters dying commonplace and its lasting impact was to teach people these sort of “events” were at best stunts and at worse scams. It's hard for a reader to suspend their disbelief and become emotionally invested in a story when they know there are no stakes. Comic books fans are intimately aware that these things are impermanent, unimportant and ultimately insignificant, and the more they see them done, the harder it becomes to care. The Death of Superman at least had some emotional resonance; The Death of Wolverine, not so much. It was an intellectual (to be exceedingly generous) exercise executed (excuse me) in a mealy “meh” manner, wholly empty of feeling.

Feeling is why people cried when Tony Stark died in Avengers: Endgame; the movie was so skillfully done, and unashamedly infused with emotion that it made grown adult people who previously had absolutely no interest in seeing movies about super people care deeply about them. Not just care but actively worry about their fates.

Earlier I wrote that Cebulski made his comments at an “unspecified Swedish comic book convention” because for the life of me I couldn’t find which one it was or when and where it was held. Which was frustrating, as I pride myself on my Internet search skills and am always interested in international comic book conventions. But I did find an article in Swedish; Marvel Comics chefredaktör: "Bra historier ska skapa känslor" dated November 2019, which translates as Marvel Comic's editor-in-chief: "Good stories should create feelings." It’s interesting for a lot of reasons, but primarily for this quote from Cebulski: “Good stories should create feelings - good or bad.” For a while now I’ve believed publishers have become convinced comic books fans just aren’t all that interested in human feeling stuff so the focus is usually on action or ideas. When if they want to sell more comics, they need to tell better stories, and to tell better stories, first they need to make their readers feel something.

*For the record, gump is a word for “a foolish or dull-witted person” which dates back to the 1800s. There’s a creature/character called The Gump in The Marvelous Land of Oz by L. Frank Baum published in 1904 and as far as I could tell Andy Gump didn’t inspire the name of the title character of Winston Groom’s 1986 novel Forrest Gump (which was made into the 1994 movie).

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.