A couple of stories last week served as a periodic reminder of the economic challenges of working as a comics creator even during boom times. Over at The Beat, Zack Quaintance posed the question, "Is it possible to have a career in comics without a second income?" using a Twitter thread from writer Joshua Dysart as a springboard. Meanwhile The Hollywood Reporter aired the grievances of established creators done out of credit and money when their contributions to the corporate-owned DC and Marvel universes showed up on screen as key elements of blockbuster movies or TV series.

Neither of these reports broke new ground. Anyone with a passing familiarity with comics, or any creative business, knows it can be extremely tough to get a foothold as a creator, and can be brutally exploitative of even the most successful stars. Or, as Jack Kirby famously advised, "Comics will break your heart." He would certainly know.

That said, today’s industry offers more options for aspiring or emerging creators than in the past, when writers and artists were treated as replaceable parts by a handful of gatekeeping publishers. Let’s take a look at the various career paths.

Inside-Out. To the extent there’s a traditional career path for comics creators, it often goes like this: recent art school grad or young writer shows some samples around a convention, gets a tryout on a lower-tier book, maybe for a second or third-echelon publisher. After demonstrating they can do professional work on time, they move up the ranks to higher profile projects, eventually catching on with the Big Two and possibly earning something resembling a living wage if they work all the time. How far that money goes depends on where they live and what kind of other expenses they’ve got.

A stint on a fan-favorite book creates a fork in the road. Down one path: take the bigger checks from the Big Two to remain as hired help, knowing that down the line, your million-dollar idea might earn you a "special thanks to…" mention in very small print somewhere after the sound designers and special effects houses have all been credited. If you’re lucky, that could come along with some residuals that, you are admonished, are only a courtesy granted by the rights owner and absolutely not any acknowledgement of your official creative role or obligation on the part of the company.

Or you can take your talents elsewhere to pursue a creator-owned title, with all that entails: rights, royalties, and the obligation to shoulder the majority of the promotional burdens of your project. The upside is that creators can make a little bit more money on lower sales volume if the deal is structured fairly, and might be in for a payday if the property is optioned. The bad news is that sales will almost certainly be lower on a creator-owned book than a top-tier DC or Marvel book, so whatever else goes into the deal better be worth it.

Option money can be great but presents the stressful choice of taking the first money you’re offered (because it might be the only money you’re offered) and potentially tying your property up in a bad or dead-end deal, or holding out for a better offer that might never arrive. Then there’s the matter of the option getting picked up, but then developed into something that you have to grit your teeth and smile about every time it comes up as the first question in every interview you ever give for the rest of your life.

For creators with ambitions beyond serialized genre comics, even the prospect of landing a publishing deal to do a graphic novel can be a poisoned chalice if the advance money is insufficient to cover the time necessary to get the book done. That’s why so many great graphic novels remain "labors of love," and why so many titles coming from major publishers have a rushed look to the artwork.

Ironically, even getting to this point in the game makes you look like a winner to most of the industry despite being only in a marginally better or perhaps marginally worse economic situation than someone at a lower rung of the food chain. In the words of glam rock band Mott the Hoople, "you look like a star but you’re really out on parole."

Outside-In. The 21st century version of this story offers a few twists. Social media allows aspiring creators to build an audience as they are developing skills. Sometimes that’s the whole story right there, as with Noelle Stevenson, who built a massive following for her charming and ingenious Nimona story as she serialized it online, leading to a publishing deal, a bunch of other creative opportunities, and eventually a bigtime production role before she turned 27.

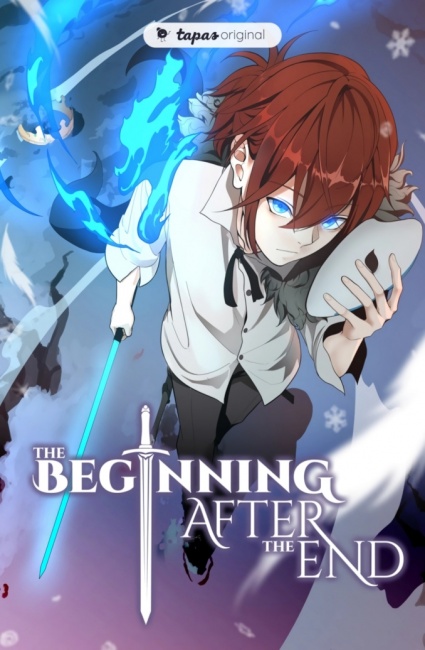

Creators like her blazed the trail, but now new platforms let these creators monetize their work gradually as they become more accomplished storytellers, under business terms that are not quite as autocratic and one-sided as corporate publishers, even if they fall short of total creative control. Webtoon and Tapas are particularly shrewd about reaching into the vast pool of user-generated content to find diamonds in the rough that they can develop into economic juggernauts. The hit mobile comic series The Beginning After the End, which has over 254,000 subscribers and 11.4 million views since its debut in 2018, was developed from a popular prose serial after Tapas paired the 27-year-old author, TurtleMe (Brandon Lee), with Indonesian artist Fuyuki23 (Duta Permana).

I don’t know for sure how much the top earners on these platforms are making, but the scale of distribution suggesting millions of paid subscriptions suggest that it’s a pretty comfortable living, especially if it’s supplemented by direct sales of merchandise and maybe a Patreon.

We haven’t yet seen the stars of the world of mobile comics cross over into print publishing or other media in a big way, but that day is coming soon. Meanwhile, Tapas seems happy to absorb veterans of the traditional comics industry like former Marvel Comics editor Chris Robinson and DC/Vertigo Editor Jamie Rich into its organization. That suggests a certain level of financial returns.

One interesting career path in comics that used a version of this model is that of Ta-Nehisi Coates, who first gained serious attention as a blogger, got hired as a columnist by the prestigious Atlantic Monthly on the basis of his work, broke through with a series of stunning essays on race, politics and American culture, then got hired by Marvel for a successful stint on a few top-tier characters before landing a gig as the writer on the new Superman feature film. So add "being a genius and a generational talent" to the list of ways to break into comics, I guess.

Building in better support. The recent griping about the economics of comics demonstrates all these models have their flaws. Freelancing for a major publisher can amount to a decent professional career as long as the work lasts, but demands constant work and attention to keep the spigots open. Trying to go it alone presupposes either a prior degree of success along the professional path or a combination of luck, talent and timing that makes any individual case of success difficult to replicate. In either case, having independent means of financial stability such as an outside job, a conventionally-employed and supportive partner, or family wealth, is the only real backstop against the uncertainties of the business.

Is there a way to make a career in comics a little more dependable? Crowdfunding has provided one new income source, but it also has some inherent limitations. The biggest problem is that project-based crowdfunding through Kickstarter remains difficult to scale. Even after a decade of growth and increasingly sophisticated efforts on the part of publishers to turn it into a pre-order and pre-funding system, it remains best-suited to one-off projects by creators who can monetize their reputations and fan-bases, and who are content to reap the proceeds of the campaign without any larger plans for retail distribution. New solutions are on the way (see "Comic Vets Launch New Crowdfunding Platform Zoop") that can perhaps close these gaps – at least for selected projects.

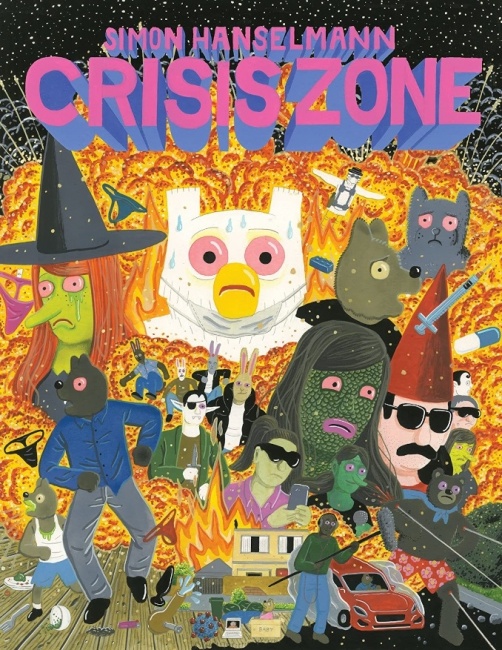

The huge amount of new investment in Webtoon, Tapas (see "In Digital Comics Mega-Deal, Tapas is Suddenly the Main Course"), and subscription-based content platforms like Substack might also put a firmer floor under the "outside-in" track, especially if book publishers can figure out how to use the serialization model to get creators paid on a regular basis while they are producing material for long-form works. The recent example of Simon Hanselmann’s Crisis Zone, which was produced as a series of strips released daily on Instagram throughout the pandemic year, then compiled into a deluxe print edition by Fantagraphics Books, shows how this could work if Instagram or another large-scale platform could work out a compensation scheme for creators working in this way.

Bottom line is that until the industry can address some of the problems of economic insecurity, creating comics will remain the occupation of those who can, for whatever reason, tolerate extremely high levels of financial uncertainty, difficult compromises, and austere working conditions in hopes of making it big… just like so many other creative professions these days.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

Posted by Rob Salkowitz on July 21, 2021 @ 2:51 pm CT

MORE COMICS

From Dynamite Entertainment

August 8, 2025

Here's a preview of Space Ghost #1, published by Dynamite Entertainment.

Dark, Erotic Manga Based on Short Story by Edogawa Rampo

August 8, 2025

Maruo brings his signature “erotic grotesque” style to a dark tale by writer Edogawa Rampo.

MORE COLUMNS

Column by Jeffrey Dohm-Sanchez

August 7, 2025

ICv2 Managing Editor Jeffrey Dohm-Sanchez lays out the hotness of Gen Con 2025.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

August 5, 2025

In this week's column by Rob Salkowitz, he looks at the industry's biggest show, held in the midst of some existential issues.