SDCC Chief Communication and Strategy Officer David Glanzer, in a phone interview Monday, was quick to dismiss any alarmism, noting that studios have skipped the show in years past and Comic-Con rolls merrily along. This year’s edition sold out all attendee badges in under an hour. More to the point, he observed that studios have all kinds of reasons for choosing not to participate (beyond the uncertainties around the SAG-AFTRA strike, which may be getting resolved soon), such as their own internal economic calculations and whether or not they have any genuinely exciting news to share with fans.

SDCC is the most conspicuous public meeting ground between comics and Hollywood, but it is not the only one. Glanzer’s observations about factors that may be impacting their choice of whether or not to engage with geek culture’s most intense fan gathering may reflect issues that could impact the whole industry.

A perfect storm of disruption. The pandemic obviously drove a wrecking ball through box office receipts, which have only recently started to bounce back. Longer term, it broke a lot of people’s habits of going to see movies in the theatre, at the same time that chains like AMC and Regal are facing economic headwinds, increasing labor costs and rents in urban locations, the closing of a lot of suburban malls, and meme-stock traders playing havoc with their market valuations.

The whole subscription-based side of the streaming business is in retreat after companies over-invested in content as a way to box out rivals in the space. Now Disney+, Paramount and Peacock are struggling, MAX is part of the ongoing Warner Discovery drama, Netflix is making up lost revenue by clawing back shared family accounts, and Amazon Prime Video and Apple TV+ are betting big on live sports.

Even without the looming threat of labor actions by actors, producers and directors to go along with the current Writers Guild strike, it’s not hard to see why doing a panel at Comic-Con isn’t necessarily top priority for the big studios at the moment.

No longer so super? As Hollywood faces a reckoning on the whole economic model it has been pursuing for the past decade, it is also seeing erosion in its most bankable genre: franchise superhero blockbusters. The Flash ran straight into a brick wall of audience indifference, garnering a disappointing $55.1 million domestic opening weekend which then declined by 73%(!) to $15.3 million last weekend. That was almost bad enough to make people forget DC’s previous bomb, Shazam: Fury of the Gods, which fizzled out after earning just $133M worldwide. Anyone care to venture an over/under on Blue Beetle?

Marvel’s latest feature film, Guardians of the Galaxy: Vol. 3, outperformed many recent Marvel offerings, taking in close to $806 million worldwide so far. And of course Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse has continued to pick up strength, proving audiences will still show up for quality and diversity. But audiences have already started grumbling that the latest MCU streamer on Disney+, the long-awaited Secret Invasion starring the formidable Samuel L. Jackson as Nick Fury, requires a “PhD in MCU” to get through the plodding first episode, and suggests that universe-building has a limit as a mechanism for mass audience engagement.

Part of this exhaustion is due to the fact that just about all the comic franchises are beating the same “multiverse” mule, trying to squeeze the same notes of nostalgia out of callbacks to legacy versions of characters and stunt casting. I wrote about this last year (see “The Methods and Madness of Multiverses”), warning that overcomplicated cosmology was a recipe for fan burnout, and it looks like the old cosmic treadmill may have finally blown a fuse.

Life after superheroes? It's way too soon to write the obituary for the superhero movie era, but it definitely seems that possibility is more likely now than it has been for a while. Does that mean the end of comic book movies? Not necessarily.

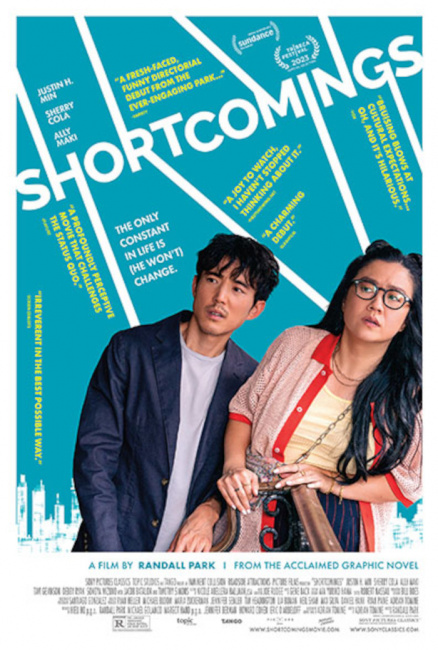

Consider two much-anticipated projects this summer. The animated feature film Nimona, based on the brilliant graphic novel by ND Stevenson, is finally getting a limited theatrical release ahead of its streaming debut June 30 on Netflix. Stevenson is one of the great talents to emerge from the 2010s explosion of YA/middle grade graphic novels, and Nimona’s first readers are smack in the prime viewer demographic by now. Shortcomings, a bittersweet romantic comedy directed by Randall Park (The MCU’s Jimmy Woo), based on Adrian Tomine’s 2005 graphic novel, got rave reviews at the Tribeca Film Festival where it screened last week, and will get a theatrical release in August. Tomine, who wrote and executive-produced the film, waited over a decade to get the movie made on his own terms.Either of these films would probably be delighted with Flash box office numbers, but then again, they didn’t cost $220 million and take five years to produce. There is a model for comics to continue to feed the Hollywood entertainment machine even if the superhero franchises get stuck in the mud, at least temporarily. It’s just not as predictable, scalable or exciting.

The boom and bust cycle. Superhero movies solve a lot of problems for studios. They represent the perfect franchise formula of big, exciting stories in which things happen but nothing really gets resolved. There will always be another sequel, another reason to catch up on all the ones you missed, and another reason to see how close an army of special effects technicians can get to realizing the vision of one artist sitting alone in a studio, drawing in pencil and paper.

Marvel’s Phase whatever-we’re-on-now and the shiny new James Gunn-helmed DC movie-verse shows studios retain a nominal commitment to the strategy, and thus to the superhero comics that inspired them, but that feels much less solid than it did a couple years ago. The temptations of exploiting corporate-owned IP rather than dealing with individual creators probably has some appeal as well.

In the meantime, we can be happy that there are still plenty of great titles and plenty of great movies to be made from comics, even if they won’t necessarily fill Hall H.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture and a 2023 Eisner Award nominee for comics journalism.