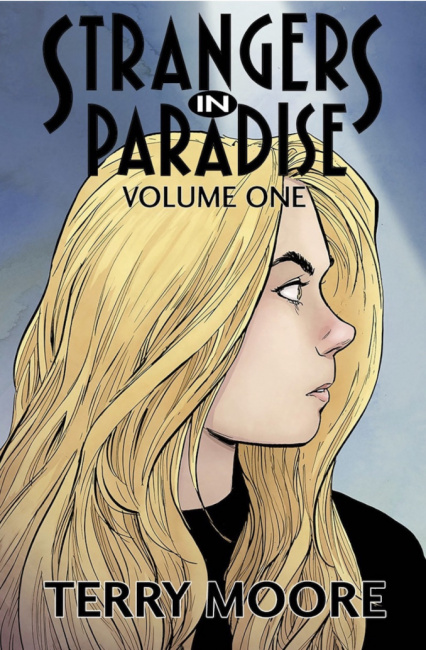

Terry Moore’s Strangers in Paradise, celebrating its 30th anniversary this year, is one of the great examples of the Direct Market at its best: a tight-knit community of retailer-fans who helped a creator with a singular and unusual vision connect with an audience just large enough to keep his labor-of-love project financially viable. Although a lot has changed in the business since the early 1990s, Moore says he is still a believer in the power of comics and the community it creates.

Stranger Beginnings. "The reason I made this story is because I wanted to read it," said Moore of his genre-busting romance-suspense-crime series when we spoke last week. "My elevator pitch was 'Apartment 3-G meets James Bond,' centered on a love triangle where no one played the roles people expect."

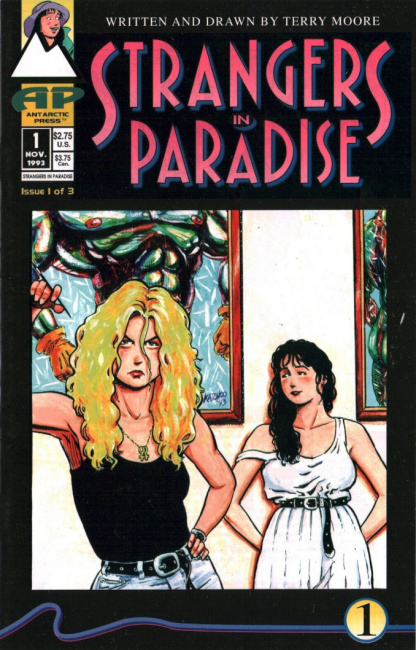

In 1993, when strong female protagonists and female-friendly storylines were not exactly common on comic book store shelves, Moore delivered both with his complex, multilayered story centering on the mysterious connections between tough Katchoo, enigmatic Francine and "sweet guy" David.

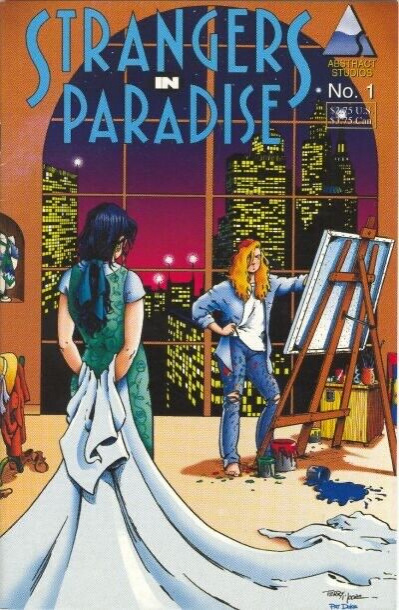

He says he tried to get publishers interested, particularly indie-friendly imprints like Fantagraphics, but couldn’t get in the door. Eventually, a conversation with self-publishing trailblazer Jeff Smith convinced him that he could get to market on his own.

"Jeff said self-publishing was the way to go. That way, you’re your own boss, no one can fire you," he said. "He explained that we had this network of distributors, like 18 at the time, but the main one is Diamond, and if you can get in with them, they can put it out to the stores. What could go wrong?"

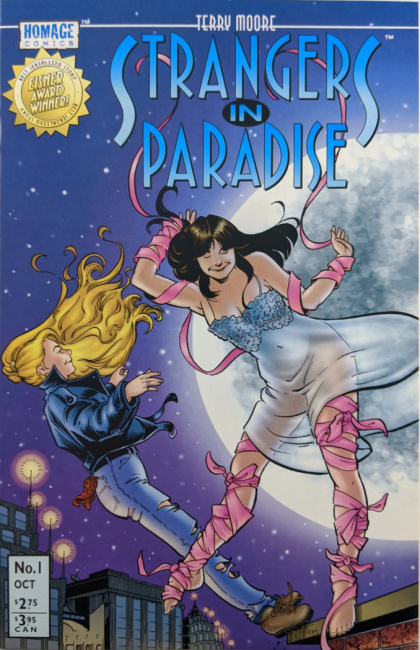

In the go-go market of the early 90s, retailers and audiences welcomed new and independent work, and SiP quickly caught on with an enthusiastic fanbase (see "’SiP’ on ‘Advance Comics’").

Weathering the storms. As dark clouds gathered around the business a few years later, the independent course that Moore and others had plotted with self-publishing started to look increasingly perilous. "It was horrifying," Moore recalled. "A lot of the smaller distributors that we used started going away, until there was only Diamond and Capital City left, and once Cap City folded, all the indie people were scared to death, so we ran to shelter with other publishers."

Moore and several others, including Smith, went to Image for a year or two, until the coast was clear. "It turned out that it wasn’t the catastrophe we all feared. What really happened is that Diamond did a great job picking up the pieces. They did a lot of out-reach, they were very accessible, and they were very public with statements to calm the market. And it turns out they were right. I realized I could go back to self-publishing with confidence in the future, and I’ve been doing that ever since."

One strategy that Moore and several of his self-publishing colleagues including Smith and Dave Sim pioneered was collecting back issues into low-priced trade paperback collections. "The print runs for our books were so small that if you missed an issue and part of the storyline, it was very hard to track it down," he explained. "The independents had trade books a few years before Marvel, and I think they saw that it was working, so they decided to try it as well."

Moore said all the trades were distributed through Diamond to the Direct Market because independents were not in a position to accept returns, a feature of the traditional bookstore distribution system. He only started thinking about getting into bookstores much later, with partners able to manage that end of the process. Even now, his main distribution strategy for the deluxe new editions of SiP is primarily through comic book stores.

Hidden influences. If the retail and distribution strategies that Moore and the other indies adopted were of their times in the 1990s and early 2000s, the style and content of Strangers in Paradise were very much ahead of their time.

Consider this: a lot of the action and intrigue in the larger SiP story arc took place against a foreground that centered the character relationships, romantic entanglements, and everyday problems of the three protagonists. The pacing of the series was sometimes quick and urgent and sometimes leisurely, taking occasional time-outs for novelty stories done in the style of Moore’s comic strip favorites (Peanuts and Calvin and Hobbes), or for deep dive character profiles.

For the most part, Moore drew the series in a clean-line style that he describes as a cross between Vaughan Bode’s "Cheech Wizard," Playboy cartoonist Doug Sneyd, and manga artist Rumiko Takahashi. "For two years before I started working on SiP, all I read was manga," Moore said. That was pretty unusual for American comics in the early 90s.

Now, thirty years later, this combination of long, serialized "romance-plus," LGTBQ-friendly genre stories and manga-influenced artwork is powering the vast majority of material popular on WEBTOON and other mobile platforms, which is one of the fastest growing segments of the business.

When I asked Moore if he had ever taken note of this, he seemed surprised and unsure what the term "webtoon" specifically referred to. But if he doesn’t read webtoons, it certainly seems like some of the makers of webtoons have read him, to the point that SiP might bear the same relationship to the currently popular material as 1930s bluesman Robert Johnson bears to rock ‘n roll: not obvious to everyone, but if you know, you know.

This affinity might also be the kind of fuel to get Direct Market-averse webtoon readers into comic stores, creating a new generation of fans for one of the DM’s original indie success stories.

Dispatches from the Terryverse. Moore says he wound up SiP in the late aughts as sales numbers began to plummet. "The trade-waiters really killed us," he said. "My whole business model is built on single issue sales. Any money from the trades was great, but you need to do the single issues to make the trades, and when people stopped buying, it began to affect everyone."

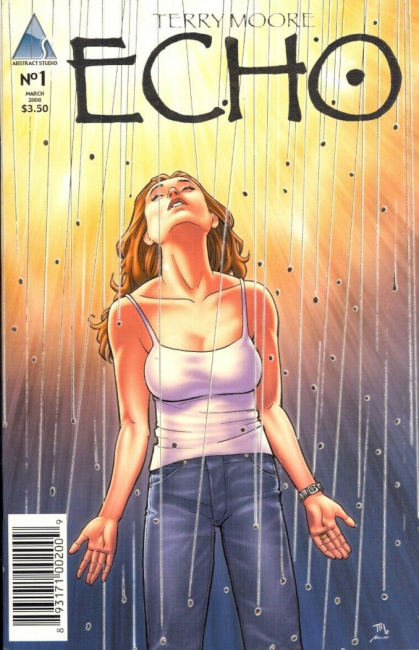

He said he decided to wind up the series and relaunch something else that would get people excited about buying single issues. So SiP gave way to Echo, Rachel Rising, and his latest, Parker Girls, stories that take place in the same fictional universe, allowing for crossovers and reunions with familiar characters like Francine and Kachoo.

Moore also says he has experimented with various formats for the SiP collections, first doing a pair of expensive and unwieldy (if gorgeous) omnibus-style editions, then a series of six smaller-format paperbacks that were more affordable and convenient, but more difficult for retailers to keep all in stock.

The 30th anniversary editions that he is now releasing combine the best of both worlds, collecting the essential run of the series in four deluxe, full-sized hardcovers priced at $30 each, featuring beautiful reproduction of the artwork and a reader-friendly format. The books are published by Moore’s imprint, Abstract Studios, and available through Diamond Books (see "Abstract Studio Signs with DBD").

Big footprints. Moore says that three decades later, he still values and depends on the community of comics retailers to be his primary bridge to fans and consumers. "The medium of comics is amazing," he said. "It has kept its popularity over the years and across the generations, and that says something about the value of what we’re doing. As difficult as it has been over the last 30 years, I think it’s pretty amazing to be working on stories that offer hope and insight. A lot of great people have worked in comics and they leave really big footprints, full of ideals and humanity. I’m really proud to be in the same industry as my heroes."

For more on the past, present, and future of the Direct Market, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture and an Eisner-Award nominee.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

Posted by Rob Salkowitz on September 25, 2023 @ 4:29 pm CT

MORE COMICS

New 'Die' Story Out in November, Alongside 'Die Quickstart RPG Guide'

August 11, 2025

The Die: Loaded #1 will be released in November 2025, the same month as The Die RPG Quickstart Game Guide.

'Hama Files Editions' Will Include a Letter from the Creator

August 11, 2025

Each issue of the Hama Files Editions will include a letter from Hama with background information about the comic.

MORE COLUMNS

Column by Scott Thorne

August 11, 2025

This week, columnist Scott Thorne notes a new twist in the Diamond Comic Distributors saga and shares his thoughts on the Gen Con releases that will make the biggest impacts.

Column by Jeffrey Dohm-Sanchez

August 7, 2025

ICv2 Managing Editor Jeffrey Dohm-Sanchez lays out the hotness of Gen Con 2025.