The creative and commercial triumph of Disney's X-Men ’97 is great news for fans, but even better news for the industry. In an era where so-called superhero fatigue is staunching the flow of big budget live action feature films and the streaming wars have staunched the flow of new prestige comic-based series, comics are practically forced back into the medium that has always served them best as an onramp for new readers: animation.

From Saturday Morning Stalwarts to Wednesday Warriors. The alliance between comics and animation was fruitful from the very start. Windsor McCay’s experimental animated films of the 1910s are as influential and aesthetically beautiful as his surrealistic masterpiece Little Nemo in Slumberland. The Fleischer Studios Superman shorts represent a peak of the artform that still stands nearly 90 years later. The 1960s Spider-Man animated show is today best remembered for its rollicking theme song and earnest adaptations of classic Silver Age stories, but it was also the training ground for animator Ralph Bakshi, who moved the medium forward with ambitious animated feature films in the 1970s.

My own first exposure to superheroes came from the Filmation DC cartoons, which aired on my local UHF stations in the early 1970s. I eventually discovered that Superman, Batman and (slightly later) the Super Friends featured in more action-packed adventures available for just a quarter at the local 7-11. Shortly afterward, I was hooked.

In the 80s, lots of fans came in through the Turtles door, and by the early 1990s, we had the classic Batman: The Animated Series, Spider-Man, and, of course, X-Men. DC kept things going into the early 2000s with Batman Beyond and Justice League, the latter of which managed to capture the magic of DC’s storytelling better than almost anything of the past 50 years.

Childhood’s End. At some point, as it became possible to realize superhero stories in live action feature films and Saturday morning cartoons faded into memory, publishers became less interested in producing kid-oriented animation. DC shifted toward direct-to-video animated features that catered to longtime fans, while Marvel’s animation, like its 2010s era Spider-Man, Avengers and (little seen) Guardians of the Galaxy, and its more recent What If..?, were tied in to the general MCU transmedia strategy more than the comics.

You can understand the economic reasons for these decisions, especially in light of the bureaucratic battles taking place within the parent corporations over the past decade. Still, the industry was missing a critical entry that had proven to be a more reliable maker of direct market customers than either kid-oriented graphic novels or manga. I’d argue that created an air bubble in the blood stream of the business that has, over time, caused some pretty serious trauma to the major organs of the industry.

Learning from Manga. Significantly, manga, which has become the model for business growth in publishing again this decade, never unlearned the lesson about the integral role of animated content. In Japan, anime very explicitly serves as marketing for the manga series, not vice versa.

And it works, both at home and abroad. There is a very clear correlation between the release of anime seasons and the sales of the source manga. A lot of the manga slump that took place from 2008-ish to the late teens is because there wasn’t much great anime coming out following the early century success of Pokemon, Sailor Moon and Dragon Ball. Once audiences got a look at One Piece, Attack on Titan, Demon Slayer and the others via Crunchyroll, Netflix and Hulu, the floodgates opened and started a virtuous cycle where popularity leads to the production of more anime, which leads to the creation of more fans, which leads to greater sales of manga and licensed merchandise.

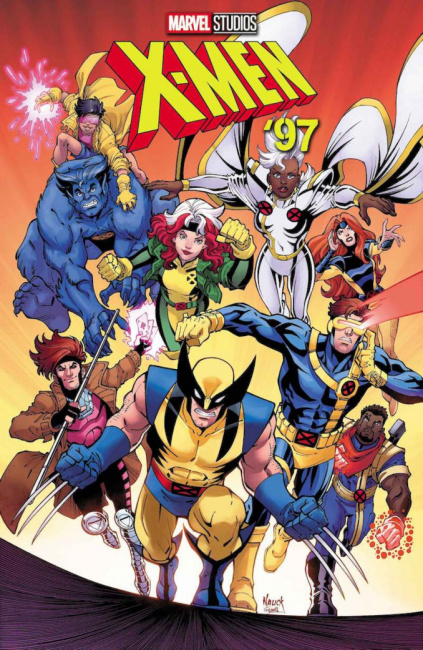

Days of Future Past. A show like X-Men ’97 may have been born in 90s-era nostalgia, because, let’s face it, the 90s look pretty good these days. But luckily the creative team knew there was more to it than going through the motions, reprising the earworm theme song, and coaching Storm through her bombastic dialogue reads.

What made the show originally appealing is that it adapted the messy melodrama of the classic X-Men comics of the 70s, 80s and 90s without irony or apology. The idea was that the over-the-top stories and cool artwork that made the comics such huge hits would have the same impact on young fans tuning in on Saturday mornings. How could any 10-year-old watch the show and not have some excitement or curiosity about the comics?

Unfortunately, the X-Men comics being published during the mid-90s heyday of the show had moved into their baroque and unreadable era, the speculator-driven retail bubble was in the process of popping, and creators who inspired the last great wave of mutant madness like Jim Lee, Rob Liefeld and Mark Silvestri were busy setting up a competitor to Marvel. As a result, the show was able to succeed on its own terms, but ended up being a bit of a dead-end from the business standpoint.

Rising like a Phoenix. Bodyslide 30 years forward to the current day and the gothic excess of Claremont-era X-Men seems like child’s play compared with the tangled lore of the MCU and the incoherent mess of DC’s media adventures. Fortunately, the creators of the new X-Men ’97 show struck the right balance between maintaining the show’s original flavor and updating the storytelling style to meet the moment.

A big part of that is how they kept the show’s original look, which was groundbreaking for its sophistication at the time, but seems dated in today’s world of unlimited CGI. The first couple of episodes of X-Men ’97 looked like they could have been produced during the show’s mid-90s heyday if the offshore animation studio were on a particularly good day.

Eventually, the producers started working in more elaborate shots and scenes that would have been budget-busters back in the day, but barely cause today’s systems to break a sweat. By ramping us up to these peaks instead of blasting us with them from the start, the show fully immerses viewers into its world. They have even managed to take the edge off the stilted voice performances without completely discarding the original characterizations.

Rebuilding the ladder? Hopefully the universal acclaim for X-Men ’97, and particularly its impact on the fortunes of Disney and Disney+, could cause the sun to shine on similar projects that evoke the same fondness for the original material. We already know a new, back-to-basics Batman animated series from Bruce Timm is on the way to Amazon Prime (after being a casualty of the Warner-Discover merger) and looks amazing (see "’Batman: Caped Crusader’ News"). A revival of the 1990s-era Spider-Man series would be especially welcome.

Things have changed considerably since animation first served as an on-ramp for periodical superhero comics, and as we all know, today’s kids have a lot more competing for their attention. But one thing that X-Men ’97 shows is that you can sometimes turn back the clock if you know what you’re doing.

Rob Salkowitz has received two Eisner Award nominations for his coverage of the industry in ICV2, Forbes and Publishers Weekly. He is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture and teaches at the University of Washington.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

Posted by Rob Salkowitz on May 20, 2024 @ 4:19 pm CT

MORE COMICS

Part of 1996 Marvel/DC Crossover

August 1, 2025

Writer Karl Kesel and artist Mike Wieringo are the creative team for the one-shot comic, which was first published in 1996 in the middle of a Marvel/DC crossover.

Crowdfunding Campaign Launches in October, Followed by Retail Release

August 1, 2025

Vault will crowdfund the graphic novel on the Backerkit platform in October, then release it to retail.

MORE COLUMNS

Column by Scott Thorne

July 28, 2025

This week, columnist Scott Thorne comments on the Edge of Eternities prerelease and on Magic: The Gathering news from the Hasbro earnings report.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

July 21, 2025

Columnist Rob Salkowitz lays out the Comic-Con panels of interest to industry professionals, current and aspiring creatives, educators, librarians and retailers.