For those immersed in the controversies that generative AI is causing in the creative community, this is an interesting, troubling, but potentially positive development. Backlash apparently did lead to the desired outcome, and other artists have been put on notice that their peers are watching and publishers are willing to draw the line. But for everyone else, what’s the big deal? Why was Mattina, whose work was popular enough in some corners of fandom and retail, singled out for a cover that doesn’t look much different from other stuff on the racks?

What’s going on? If you haven’t been following along at home, here’s the rundown. Last week, DC solicited a variant cover for Action Comics #1069 by Mattina. Artist Adi Granov noted a tell-tale sign of AI art, a small flaw in the image (in this case, an imperfection in Superman’s "S" symbol) that a human artist would not make, especially not in such a labored, rendered piece. Granov blistered Mattina in a social media post that not only called out this example, but also noted his generally poor reputation as a swiper, "photobasher" (manipulating digital photos to create backgrounds and other pictorial images) and shady character dating back decades.

Apparently a lot of people have knives out for Mattina because the online response was nearly unanimous, and over the weekend, DC’s revised September solicitations includes replacements for all the variant covers that he was in line to deliver, including Superman #18, Brave and the Bold #17, and several others. Mattina has already reportedly been blackballed at other publishers over accusations of plagiarism.

So, problem solved, justice prevails, nothing to see here, right? Well…

Why AI art is problematic for publishers. The rise of generative AI is largely a top-down phenomenon, driven by billions of dollars of investment by big tech companies who have developed a solution in search of a problem (see "The High Cost of FOMO is Coming Due"). Many of the products rushed to market have some glaring technical flaws, like the weird errors and inconsistencies that tend to give the game away in cases like the Action cover.

But the bigger problem for publishers is that courts are starting to rule that AI content is not subject to copyright protection, in part because it is synthetic, and in part because the underlying data models were built using content obtained without the permission of the original creators.

When publishers hire artists, they are buying all worldwide publication rights to the image, although the artist still owns the original. But with a work that includes AI-generated content, the rights may not be the artist’s to sell. If "nobody" created the cover, then "nobody" owns the cover, which means anyone can make mugs, t-shirts, or their own comics using that image. Not awesome, especially if you are a global media conglomerate, like Warner Bros Discovery, and the work includes a trademarked character like Superman.

This remains a gray area because what if the human artist was simply incorporating elements from AI into a work that was otherwise made by hand, in the same way that an artist might manually or digitally trace a photograph to use in a background? The law recognizes that the creative process encompasses borrowing and adaptation of existing work even without the explicit permission of the original content owner, so why not with AI as well?

The short answer is, we don’t know, and I don’t envy the courts having to sort it out.

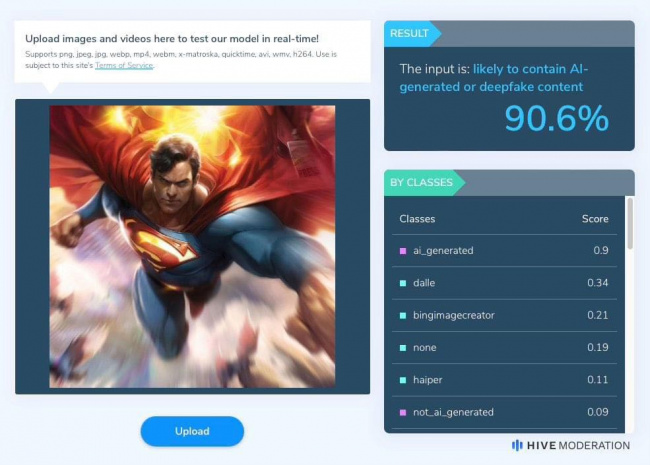

How much robot is too much? Hive, a commercial developer of AI-based content moderation technology, recently released an AI detection tool for text and images. When I dropped a jpg of Mattina’s Action Comics cover into the tool, it concluded that the image was only 12.7% likely to contain AI-generated content, despite failing the "eyeball" test. That’s bigger than zero, but still a sliver. However, using a higher resolution, cropped version of the cover yielded significantly more conclusive results of 90.6%. [additional info updated: June 25, 2:30 CT - ed.]

So what if synthetic elements are composited into a multilayer file that also includes hand-drawn artwork, commonplace digital filters like motion blur, and other elements? What if AI generated the composition and color palette (things that AI image tools are actually pretty good at), but the artist then redrew the image by hand? What if the artist used AI to create a reference for something that’s hard to find a photograph of, like a historically accurate 9th century Viking city or a yeti?

Does 1% robot involvement mean the work is tainted? If you ask the art community, the answer is an emphatic yes. There is a huge groundswell of anti-AI sentiment driven by the moral outrage of tech companies helping themselves to copyrighted works to train AI systems that seem designed to replace creative professionals, aggravated by a generous helping of tech-bro triumphalism.

But in terms of copyright, it’s harder to say. This problem gets even more tricky when you get outside the world of art and imagery.

The plot thickens. Artwork is just one implementation of generative AI. The much bigger one is chatbots, which broke into the mainstream with Open AI’s ChatGPT, and are now popping up, uninvited, into every piece of software and app you can think of.

Some critics have been having fun pointing out the weird issues of chatbot hallucinations, such as when Google’s bot suggested putting rocks on pizza, or their penchant for regurgitating the biases present in the data they were trained on. And that’s true. Glitching robots can be hilarious, at least until they get their hands on the nuclear codes.

However, chatbots can be genuinely useful if you’re a professional writer, especially of fiction: not for writing finished prose, at least not if you care at all about expressing yourself in a distinctive style, but rather as a story coach. If you have some general ideas about story direction, characters, setting and genre, and also have some skills in your craft as a storyteller and wordsmith, ChatGPT and its robotic relations can simplify the process of blocking out story beats, scenes, character arcs and structure.

Just for laughs, I walked ChatGPT through the process of plotting a 5-issue miniseries where Sherlock Holmes and the Shadow team up in 1930s London to foil a scheme by Shiwan Khan and Professor Moriarty, featuring a lively rivalry between Watson and Harry Vincent, and Margot Lane developing a crush on Holmes (she likes men with strong noses). It took me about 45 minutes of pushing, prodding and molding the output based on my own sense of the characters and plot to get a very tight outline.

Now I’m not an expert on this kind of writing and don’t do it for a living, but I do read a lot of comics and genre fiction. The story we "collaborated" on was not half bad – maybe less than 12.7% bad, in fact – and it would not have taken much to make it my own, without any hint of its AI roots. But really, where’s the fun in that?

Drawn by robots, written by robots, read by humans? The central question with AI is not whether it can serve as a decent crutch for creative tasks. It seems to be able to, as long as you are smart enough to cover your tracks. The question is, how much of this output do we want or need, and why would we ever want art or stories created by anyone other than human beings?

I could ask ChatGPT, but I’m not sure if I would trust the answer.

Rob Salkowitz has received two Eisner Award nominations for his coverage of the industry in ICV2, Forbes and Publishers Weekly. He is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture and teaches at the University of Washington.