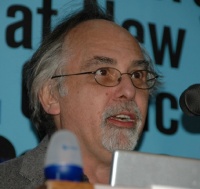

In his Keynote speech at the ICv2 Graphic Novel Conference held at the New York Comic Con, Art Spiegelman chronicled the history of comics, remarking on the medium’s dependence on print technology from the primitive lithography behind Rudolph Topffer’s first comics in the Western tradition to the color presses that Joseph Pulitzer made essential for every major newspaper to print Sunday comic supplements and which led directly to the printing of the first modern comic books in the 1930s. Spiegelman also took a peek into the future in which some sort of “Kindle”-like device has rendered most books on paper obsolete but speculated that comics, because of their essential “bookness” would endure.

Novelists may not care about the color of the book cover under the dust jacket, but according to Spiegelman, “Cartoonists all care, every single one of them. It’s because they’re making a book. And a book asks for something. It asks you to make your artwork a certain dimension, a certain size, so it looks good on the page. It takes advantage one way or another of the elements of book design. It’s part of the core of what comics at least have been.” This essential relationship between comics and the form of the book is the reason that Spiegelman concluded that in spite of the fact that comics may well spawn some new semi-animated format to take advantage of 21st Century technology, “In a way, one might think that the comic book will be the last book left standing.”

While Spiegelman provided an excellent overarching view of the development of western comic books (including an interesting aside in which he blamed the German Enlightenment philosopher Gotthold Lessing’s philosophical treatise Laocoon for the intellectual disrepute that still clings to comics), perhaps the most interesting and humorous portion of his address was a very personal history of his involvement with comics from his first exposure to the medium as a kid growing up in the 1950s to his creation of Maus and the publication of RAW magazine in the 1980s.

To illustrate this compelling subjective chronicle of comics in our times he used slides that reproduced autobiographical elements included his recent updated edition of Breakdowns. Among the many images he showed was a page from Dr. Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent in which the good doctor demonstrated the secret symbolism within comics that drove kids to juvenile delinquency—in this case a detail of a male character’s shoulder, which upon closer inspection revealed the image of a naked woman’s torso.

Spiegelman also spoke incisively about the nature of the medium itself, using an image of an icepick about to puncture an eyeball as a metaphor for the immediate impact that the images from comics can have on the brain. He talked about his latest project with his wife, Francoise Mouly, who is editing Toon Books, graphic novels designed for young readers, books that use simple, easy-to-read words to tell stories that interest kids and demonstrate the possibilities and pleasures of sequential storytelling.

In addition to detailing the properties of the medium, Spiegelman put comics squarely in the midst of the perennial battle at the heart of American culture between the “vulgar” and the “genteel,” coming down clearly on the side of the former in his dislike of the term “graphic novel,” because it reeks of “respectability” and is as much of a misnomer as “comics,” which implies humor. Spiegelman prefers the underground appellation “comix” not out of nostalgia, but because it suggests the very mixing and miscegenation of media that Lessing deplored, but which gives comics its unique character and vitality.

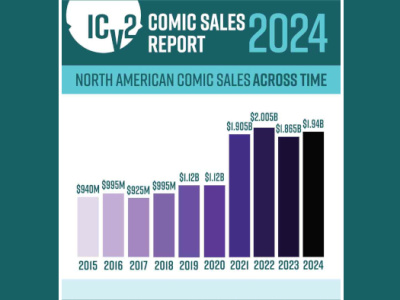

Spiegelman also talked about the movies, which he noted could produce powerful sales drivers (“A Watchmen movie alone has kept you from being in the red this year,” he told the assembled audience of comics professionals), but which he warned is “a much more dominant art form than comics.” Movies, Spiegelman appeared to suggest, also represent something of a challenge and a danger to comics, noting that in spite of the fact that both media rely on a combination of words and pictures, “Comics and movies are cousins but not brothers, I think.”

Finally Spiegelman asserted that the real future of the comics medium lies in the avant garde, not in comics that are trying to be storyboards for films yet unmade. “The avant-garde of comics is ultimately where your future lies, even if you don’t think so. It’s what lets things happen. And by avant garde I mean things like this crazy issue of Kramers Ergot that’s about as high as this podium. It’s bigger than most Sunday comics were at the end of the last century when they were bigger than the New York Times. And half the work here I don’t understand. This is good. I know that Picasso had a really hard time figuring out Jackson Pollock.”