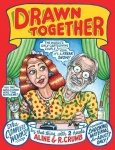

We recently had the opportunity to talk to Aline Kominsky Crumb, a seminal figure in American comics. Best known as the wife and collaborator of Robert Crumb, she played a key role in expanding the role of women in comics and in the development of autobiographical comics. In Part 1, we talk about Drawn Together, Norton’s recently released compilation of her work with Robert Crumb. In Part 2, we talked about her role in the early history of comics by women and autobiographical comics.

We recently had the opportunity to talk to Aline Kominsky Crumb, a seminal figure in American comics. Best known as the wife and collaborator of Robert Crumb, she played a key role in expanding the role of women in comics and in the development of autobiographical comics. In Part 1, we talk about Drawn Together, Norton’s recently released compilation of her work with Robert Crumb. In Part 2, we talked about her role in the early history of comics by women and autobiographical comics.Whose idea was Drawn Together and how did you get started?

Drawn Together is forty years of work that Robert Crumb--my husband--and I have done. It was his idea. We started in 1973 working on just some pages together because it was raining and I had broken my leg. He was trying to keep me from driving him crazy. When he was a kid he had drawn two-man comics with his brother Charles so he got the idea of trying to do it with me just to keep me busy. I really took to it and we seemed to be able to write naturally together--to go back and forth with a natural dialogue.

So we worked on the first one and it rambled all over the place. It was kind of incoherent but it was fun. We had aliens appear and Timothy Leary shows up and all kinds of crazy stuff, true and not true. We hadn’t really intended to publish it; we just did it for ourselves. At some point, Keith Green who is Justin Green’s brother who was publishing at the time came up to visit us. He saw it and he wanted to publish it so we said "All right, we’ve got like 30-something pages. Why not?" We didn’t have a title so we showed it to a bunch of friends and one of them was Terry Zwigoff. He read it and said, "This is the most embarrassing thing I have ever seen. You might as well just hang out your dirty laundry for everyone to see." And I said, "OK, there’s our first title." So that’s how we started on the Dirty Laundry series which was the early stuff we did together.

And then on and off we kept working together on different projects for local newspapers. We did a bunch of different stories together and then we did some stuff for The New Yorker and then we did Self- Loathing #1 and #2 where we each do a long story and then meet together. Then for Drawn Together we did a bunch of new stuff at the end.

We do it on and off. We carry a notebook with us and kind of get into this George Burns and Gracie Allen stand-up mode when we’re working on this stuff. It’s actually very enjoyable.

Is Drawn Together all of your collaborative work?

Pretty much; what we could find. There might be pieces floating around here and there that we never got back or forgot about but this has stuff from the local hippie newspaper in California where we lived, and political stuff, and it has stuff from Whole Earth Catalog and all kinds of other weird odds and ends--what we could get together is in there.

The collaboration seems to vary in terms of what each of your contributions are. Can you talk about the process of collaboration--where do the stories come from?

It depends. When we travel a lot of times we just keep a notebook and when we think of something that’s a good story or we experience something, we always write our notes down. We’ve got a whole book full of stories that we could do at any time. Sometimes we just write up a bunch of stories because we feel like it.

For The New Yorker it was different because they would give us a subject or sometimes send us on an assignment like the Cannes Film Festival or Fashion Week. That was different. For The New Yorker or magazines like that we’d have a finite number of pages, so that we worked on in a different way. We wrote the story in a very tight and precise way--planned it out a little bit more. When we were doing the longer stories, we would have more open leeway and we let stream of consciousness enter into it and did more of what we wanted.

There’s different ways we worked on it but we always pencil the dialogue first on however many pages we have. We don’t do any inking to begin with and then we each pencil our own character and we pass it back and forth, and then we each do our writing in ink, usually with a Rapidograph, and then we do our drawing, usually with a crow quill. We each do ourselves and we pass the page back and forth. I do some backgrounds; Robert does more backgrounds because he’s faster and does it much better. I can’t draw cars or anything like that. So if there are any cars or buildings, he gets stuck doing that. If there are other characters, we take turns drawing them.

We have a pretty efficient way of doing it. It’s tough to do very tight penciling because sometimes where one person touches the other or melts one into the other, you have to be careful. Otherwise it doesn’t seem very complicated anymore to do that.

Who’s your audience? Is it the same people, just older, or are you picking up new ones along the way? When you do signings, who’s coming?

It’s surprised me. There’s always a couple of old hippies, or a lot of old hippies, like us with piles of books who have been hanging in there for years; and then there’s young people--all kinds of different young people; and now there’s more third world people--all different nationalities of young kids who are interested in comics. They teach comics in art schools. You get these art students who want to draw comics. A lot of those are coming. And sometimes, surprisingly, very straight people-- a couple of librarians here and there. Kind of a weird mixture of people.

I just did a book signing at the Miami Book Fair and there were people from Long Island who grew up where I grew up that came. That was really interesting. And some other people that I had exercised with at the gym over the years. Different odds and ends showed up, so that was a pretty interesting group. But it’s a mixture, definitely.

What’s the gender mix like?

Half and half because a lot of women are interested in what I’m doing.

Click here for Part 2.