'I Think I Can Manage' is a weekly column by retailer Steven Bates, who runs Bookery Fantasy, a million dollar retail operation in Fairborn, Ohio. This week, Bates shares his store's experience with trading cards:

In case regular readers haven't noticed, I'm pretty proud of Bookery Fantasy, the shop I've managed for almost 18 years now. In terms of comic book and gaming stores, I contend that it is one of the best in the nation, with a diverse selection, excellent customer service, and fair prices when both buying and selling. In the mid-1990s Marvel Comics dubbed The Bookery a 'megastore,' and comments from customers traveling through the area compare us favorably to the better shops in New York, Chicago, LA, and elsewhere. So I feel justified in extolling our virtues every now and again.

But what about our failures, our weaknesses? Like all businesses, The Bookery has an Achilles heel or two, things we just don't do as well as our competitors. One such area is cards. I'm not talking about Pokemon, Yu-Gi-Oh!, or Magic: The Gathering and other collectable card games (though we do generally downplay CCGs compared to miniatures and role-playing games).

Non-sport or entertainment and sports cards are an important part of the specialty store mix. Many shops have made small fortunes dealing in baseball and football cards over the years, offering rookie cards of star players, selling unopened packs at a premium to collectors feeling lucky, or just offering singles to complete whole sets. Other sports have done well in card form, such as NASCAR, hockey, and basketball, sometimes outselling baseball and football in certain regions. The 'king' of sports cards has long been the Topps Company, a name recognized by virtually all sports card collectors.

While some comic book shops work well 'bundled' with a sports card dealership, our experience was decidedly otherwise, and we sold out our stock of football, baseball, and related cards in the early 1990s (fortunately avoiding baseball strikes and other blows to the hobby). At the time, competition was fierce for sports cards, and, without a sports nut on staff, we were ill-prepared to keep up with the volatile nature of prices. If a rookie hit a grand slam home run in a Monday night game, by Tuesday noon we were sold out of his card, at common card prices. So, we bailed, and never looked back.

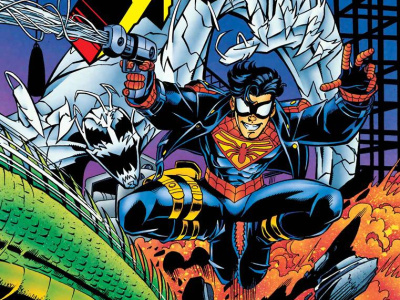

Non-sport cards offered an opportunity for us to stay in the card business and seem intelligent doing it. After all, it wasn't like Spider-Man was going to see a spike in his rookie card, right? But entertainment cards offered their own challenges, not the least of which were 'chase cards.' Randomly-inserted in regular packs of cards are special cards, often with some sort of enhancement to separate them from the chaff, like foil, or a hologram, or die-cut imagery (or all of the above!). Such short run cards would bring big dollars, selling to completists and collectors who concentrated on rare cards.

Generally speaking, we did well with non-sport cards, for a while. Selling both common and chase cards, sealed boxes, packs, and sets, our cash flow made it seem like there was a real profit to be made in these entertainment cards based on comic books, TV shows, and movies. Even Desert Storm and Famous Rabbis had cards! But the mark-up on cards was abysmal, especially with the wholesale flea market dealers (who were 'picking' boxes, cleaning out the chase cards and selling only the commons) and competition from Internet auctions. As prices rose at the distribution level, resistance to higher pack prices forced us to sell at even lower mark-ups. And loose cards, commons, often traded at 2-for-1 with no actual sales, had to go.

When we downsized our card section, it was not an impulse decision. We stopped buying back (or trading) sets, commons, and chase cards, and only sold sealed boxes and unopened packs. With only a few exceptions, we stopped breaking down boxes ourselves, offering more opportunities for customers to get the rare insert cards. Since we were carrying CCGs by this point, we continued carrying card supplies, such as nine-pocket pages and clamshell boxes. In theory, we should've increased our profits at the same time we reduced the clutter and workload associated with commons and chase cards. In theory, mind you.

The problem with our plan was painfully obvious. Card customers, like comic book fans, gamers, sports enthusiasts, philatelists, and other collectors, wanted a clubhouse, a place of refuge, where they could not only buy, sell, and trade their cards, but where they could gab about them with other like-minded souls. By eliminating the 'swap meet' aspect of the business, we had, in essence, put out a gigantic GO AWAY sign to card customers. Sure, a few pack-by-pack people remain, but by and large, cards only exist in our store today as loss leaders and impulse buys.

A great sitcom dad once said 'If something is worth doing, it's worth doing well.' Truer words were never spoken, especially if applied to specialty store retailing. I'd be interested to hear how successful card dealers run their businesses, but I'd venture a guess that they make their shops a safe harbor for collectors, offering a fair buy-back or trade-in policy, singles (commons, uncommons, rares, chase, and variants), a diverse selection of competitively-priced product, collection protection supplies, and, most importantly, a welcoming atmosphere where they are appreciated. Companies like Comic Images, Topps (still making Star Wars trading cards 27 years later), Rittenhouse, offering numerous licensed SFTV properties, and Inkworks, with Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel cards, all produce high quality trading cards certain to appeal to hobbyists. Selling non-sport cards to enthusiasts shouldn't be a problem. Keeping the customer satisfied is another story.