GKR: Heavy Hitters is a combat sports board game set in a post-apocalyptic world where giant robots compete for dominance in the ruins of abandoned cities for their corporate sponsors. At stake are lucrative salvage rights and advertising dominance, as the battles are streamed live around the world as entertainment. Players take the role of team leader, piloting a fighting mech and deploying a robotic team of support units (Combat, Repair, and Recon) to dominate the battlefield and win the favor of consumers for their sponsors. The game is for 2-4 players. MSRP is around $100.00

The Kickstarter launches on February 22. There will be a retailer level which will include 5 copies of the game for retail sale, one demo kit, and promotional materials.

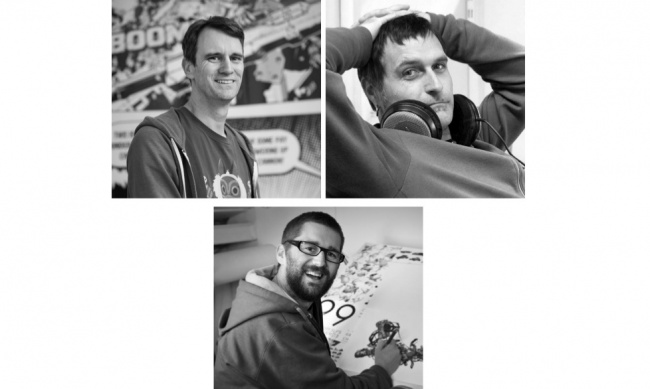

ICv2 recently spoke with designers Paul Tobin, Leri Geer, and Christian Pearce, along with Weta Workshop Publishing Manager Karah Sutton to learn about the creation of the world of Giant Killer Robots, and the first board game, GKR: Heavy Hitters, designed by Matt Hyra (DC Comics Deck-Building Game, Vs. System, World of Warcraft Miniatures Game).

In Part 1 of this two-part interview, we talk about the origins, influences, and nature of the world of GKR. In Part 2, we talked about the collaboration with Cryptozoic, the decision to use Kickstarter, the plan for trade release, and the future of the game after launch.

Maybe you can start out by telling us where this concept came from, how it got started.

Paul Tobin: It's a little bit of a complicated backstory, so I'll try to condense it as much as possible. Mike Gonzales, who was our head of consumer products, brought the opportunity to us, the designers at Weta Workshop.

He was friends with a company called Trigger, who are an augmented reality company that, like Weta Workshop, does quite a lot of service work for film. They were keen to make an augmented reality board game. The working title was Giant Killer Robots.

Originally, what Mike asked us was whether we would be interested to design a world that this augmented reality board game could play out in. That was how the project kicked off. As the project evolved, we obviously needed to hire a board game designer.

We got Cryptozoic on board, which was awesome, pretty amazing to get such a big‑name company interested in working with us. As things moved further and further along, we started spending more focus on the board game aspect of it, and the augmented reality part of it started to drop off a little bit, especially when we went to four-player, because with four players there were some limitations around the technology, and so we just ended up focusing on making purely just a board game with Cryptozoic.

How would you describe the target audience for the IP?

Leri Greer: The target audience? I think we thought of it the other way around initially in the sense that we're three designers ‑‑ Christian Pearce, Paul Tobin, and Leri Greer; we've been designing for some number of years.

When you're designing for film it's in service to the film or in service to directors and making their vision come true. I think in this particular instance the opportunity came to us to just do what we wanted to do, rather than what we were told to do.

As far as the target audience goes, in a way we were just trying to please ourselves, and we hoped that because we are people that are steeped in nerd-dom and the science fiction genre, that if we liked it, other people would like it. We just went back and searched through all those things that impressed us when we were teenagers or through our twenties.

Tobin: Obviously when you're making a game you need to think about who's playing the game. We very quickly established that we wanted to make a game that people like us would want to play, versus making a game that my niece would want to play.

When you look at the films that we're involved on, like District 9, Avatar, Chappie, Hobbit even, there's a certain maturity to the worlds that we build. I think that that's, in all fairness, the kind of worlds we like to engage with and with a certain level of maturity and practicality to them.

In terms of a target market, we intentionally chose to not make a game for kids but more for an adult market.

Did any of the game concepts come out of the films you've worked on in the past and you thought, "Oh, I can't use it for this. I'll just stick it in a drawer and pull it out when the opportunity arises"?

Christian Pearce: I wouldn't say that it was anything that we had sitting around waiting for the opportunity to use, but this game and the way it looks is definitely like an evolution of what we've done here for so many years. In a way, it's a pinnacle. This was much easier to design for than working for a director.

Working on films and stuff will often deliver hundreds of designs over a year or more, but on this one we knew what we liked and it would be like what you first design for the guys and it's like, "Oh, what? People like it? We're just gonna go there. Great."

That never happens. We would never have got to that point without all the years of working on the science fiction films that we've done. Yeah, that stuff was really flowing out of us. It wasn't a struggle at all.

Was any of robot combat actually influenced by work you did for District 9, Chappie, Avatar, or other movies?

Greer: It's the other way around. It's because we designed on those, it's not so much that we're influenced by that, but we designed a lot of the stuff in those movies. Probably the question is more, is our aesthetic or our visual design language or the things that we like and respond to that were in those movies, are they in this property?

The answer is yes. Like what Christian was saying, it’s because we're concept artists and we sit there all day drawing, and basically we have our opinion on what's the coolest thing that we'd like to see on film.

Often times that's not what ends up on the screen because directors usually have another thing that they're going for. In this particular instance, exactly what we wanted the robots to look like is exactly what they look like.

Pearce: Leri put that very well. The films that we've mentioned, they get described as having the Neill Blomkamp look, or the James Cameron look, or the Peter Jacobson look.

A lot of it happens to be what we've done on it, particularly with Neill Blomkamp. He shares such a similar aesthetic to us that we're not having to distort our vision too much to make him happy. It's what we already like.

Tobin: That's why he comes here, because he likes what you guys design, and you guys are in lockstep around the use of graphic design and consumer-based corporate subversion.

If you're wanting to talk about inspiration and influence there are some very clear points of reference that this IP, this world of GKR has definitely spun from. We're guys that grew up in the '80s. We grew up on RoboCop, Starship Troopers and Total Recall, those kinds of subversive films of the future where it's having a go at corporate consumerism, but in a fun and playful way. Also anime. Anime and manga, are a big influence. That's been probably the biggest influence on this particular property, is being inspired by that stuff growing up and wanting to do our version of it.

It occurs to us that this is some pretty high powered designers to be working on a world for a board game. Do you envision other potential uses for this world you've created?

Tobin: Absolutely. In fact, for us, the real opportunity, obviously, with doing this board game is that it's been a phenomenal opportunity to help flesh out a world, some characters, and a basic story idea, all of those ingredients that you need to start to work on a film or TV series.

The board game has been a fantastic way of being able to explore all of that in a much more fun way in some ways, because we don't have to lock ourselves down to a script straight away. We're not chasing film studios from day one.

It's actually been a really nice job to piece-by-piece different things and try different things out that we wouldn't normally be able to do if we were just trying to pitch this as a film or TV series from the get‑go.

Having said that, we're big board game enthusiasts. It's not like we were unhappy about the idea of working on a board game. We've done films for over 14 years now. The challenge to do something different, and something we haven't done before, is really exciting.

Were there any board games that were major influences on this project?

Tobin: I grew up playing BattleTech as a kid, the roleplaying game version. Most of us have had some exposure to robot rumble kind of games. One of the ways we were really keen to work with our game designer partner Cryptozoic, was we didn't want actually want to dictate the kind of board game too early on.

What we did was we just came up with the world, at least the bare bones of it. Then we had a couple of great meetings, where we talked about what we thought was the opportunity to design a game in that world.

We wanted to avoid what we’ve seen play out in other games including a lot of video games. It was more about leading Cryptozoic to come up with a board game that suited the world that we've made, rather than come in prescriptive and say, "Oh, we wanted to be like this particular board game. Let's just rip off that."

Click here for Part 2.

See miniatures and game components in the gallery below.

View Gallery: 9 Images

View Gallery: 9 Images