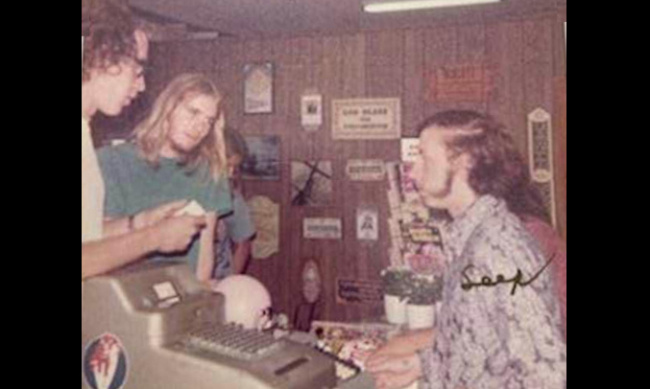

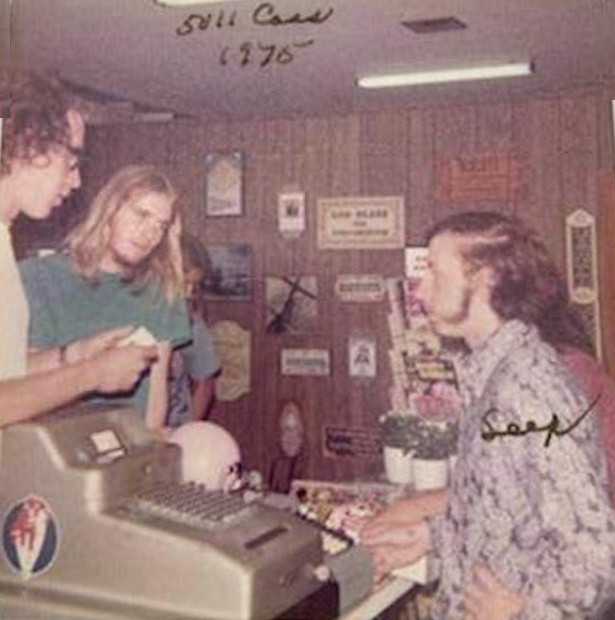

Mike Towery and Richard Alf (one of the founders of San Diego Comic-Con) at the first Pacific Comics store, with Steve Schanes behind the register.

To watch a video of this interview, see "ICv2 Video Interview – Bill Schanes."

This interview and article are part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

When did you start handling new comics?

When the stores… We were buying some comics from the San Diego Periodicals, the local ID [independent distributor] to fill up the missing holes or the newer issues for the back issues in the mail order part. We started buying in real bulk when the first store opened.

Were they letting you buy by title, or were they just giving you an assortment, and then you returned what you didn't want?

We asked to come down in what they called the cherry line, the picking line. They'd put them on conveyor belts, and then their workers would come and pull out five copies for every 7‑Eleven, do it 500 times in a row, whatever. We said, "We just want to walk down the line and pick out what we want. Then you can add them up at the end, because they're all the same price. Just count the number of books we'd bought and multiply it out."

What did you call that? What kind of line?

They called it a cherry line.

I remember "tie lines."

Tie lines is another name they called it. It was on rollers, and they just put the bulk—well, back then, actually, they came in brown bags, not even boxes, and they were string tied by metal bands, not by the plastic wraps. You knew the top copies and the bottom copies in every pile were not mint, but they were giving those copies to the 7‑Eleven, the tie lines, the draw lines.

I'd go to the middle of the pile and pick out my 5 or 10 or 20 copies. They're like, "Why are you doing this?" "Well, I don't want ones that have the crease marks."

We started buying some books there and more and more books there. It ended up being we were buying about two‑thirds of all the comics being shipped to San Diego. When they were doing the line, we would come in and say, "What day do you set the line up?" They go, "This day."

We'd be the first one in the shop that day, the warehouse, and take the top copies and the bottom copies off and take everything in the middle for our stores and for the mail order.

What were they selling to you at?

A whopping 20% off, non‑returnable, but if I was a 7‑Eleven, I’d get 20% off, fully returnable.

But you got to pick what you wanted?

I was being punished for non‑returnable.

Right.

Crazy, crazy stuff. Many of the IDs back then, independent distributors, newsstand distributors, these were old‑fashioned, [gangster] businesses. They had done it one way forever. They didn't negotiate. They were heavy‑handed and they were ruthless.

I see you know the IDs.

Big time. They made it very clear that we were insignificant, like, "We're putting up with you, but don't bother us."

How did you hear about direct distribution?

From the owner of San Diego Periodicals. We were buying this bulk quantity from them, and we had asked for a better discount than 20% off. So eventually they gave us 25% off. Then we asked for 30% off, and he said, "I'm not doing it. In fact, I don't want to sell to you anymore."

We were like, "Oh‑oh, that turned really bad for us. Now, we're not going to get 25% off. We're going to get nothing off. We're not going to buy new comics unless we buy them cover price." I said, "Where do we get them from?" He said, "Well, just call up Marvel and DC directly."

We didn't know any better; we’re like, "OK." We looked inside the indicia, and it was New York City. I think we called Marvel first, and they told us about Phil Seuling who had just started up buying from the publishers on a non‑returnable basis. He was really the first to do that in any kind of meaningful way.

You could buy from him on a prepaid basis, two months in advance, but you had to buy in increments of 50 per title. You couldn't say you want 8, 12, 21. You had to buy 50, 100, 150, 200. That's how the interior wrapping was done at the printing plant.

For Phil Seuling and Jonni Levas, Phil's partner, they'd just grab a bundle and ship the order very quickly. They opened up a warehouse very close to the printing plant in Sparta, Illinois where they could be more efficient in shipping the comics out.

We called up Phil, set up an account, scrapped together some money, bought our first order from them. We knew that, on the better‑selling titles, we'd need multiple 50s. On the poor‑selling titles, we had too many books.

Right.

We had to have everything in our stores, so we had to find other stores to sell our extras to. We said, instead of buying 50 and selling 12, let's buy 50 and sell 38 to somebody else, in bulk. Other comic stores had started to pop up around town in Los Angeles and San Francisco, Colorado, Arizona, just starting to pop up. We were by no means the first stores, although the first in San Diego. There were certainly stores in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and, of course, in New York.

What were some of the LA stores then?

The LA stores would have been Cherokee Books. A very famous Malcolm, I wish I knew his last name (his first name was Malcolm, I'm pretty sure) he had bought a bank, like a bank building, and had bulk rare comics, spine out, no boxes. There weren’t white boxes back then.

You'd be walking through, bending the spine to find the one you wanted, but no one was thinking about condition a whole lot. You were just looking for Superman #28 or whatever.

There was Cherokee Books. There was the American Comic Book Company, up in Studio City, David Alexander and Terry Stroud. Nick Scotto, kind of an infamous distributor back in the day, kind of tough guy. I don't remember the name of his store, but he had a store in the '60s that was dealing in remaindered comics from the IDs. He was buying them at the back door and putting them in his comic [shop].

Remaindered comics, right?

That's exactly right.

Meaning they had gotten credit for them, for returning them or destroying them, but then sold them to dealers, which was throughout the United States at the time.

You were supposed to strip off the covers and then return the covers back to the publishers or the national distributor. The local IDs were so unscrupulous, they said, "Just trust us. We ripped the covers off." They were basically double‑dipping. They were getting full credit back from the national distributor or the publisher, and then selling them at the back door for wholesale prices. For them, comics were good business, except they were a tenth of the price of all other magazines.

So the Seuling increments were why you got into distribution, it sounds like.

We were buying too many comics for our stores, and other stores also noticed when we opened, and they said "We’re going to open a store, can we go together to buy something?" It was kind of a mutual thing. They knew we were going to make a little money on them, but we were also doing all the administrative work and all the trafficking and the labor to break them down.

When we took up San Diego Periodicals on the offer to go direct, first with Sea Gate and then with DC…

Well, their offer to go direct, right?

Yes, it was the foot out the door with my butt. While that was happening, I was going to high school in San Diego. My brother Steve had given me his first‑year Honda car. Honda was a motorcycle company, and they started doing cars with the motorcycle engine turned on its side and all the car’s made of fiberglass. There's no metal in the car at all. So they were very, very light, almost like the early VW bugs. Four people could pick up a Honda car, four people—not weight‑lifters, just four people. All of a sudden, in my freshman year, all my tires were getting popped every day. I was getting four flats every day.

Sometimes, my car would be moved to a different parking spot with four flats. I parked in the high school parking lot over here, but the car was on the back side of the school when I got out of school that day. They were sending a very distinct message about how unhappy they were that we decided to leave.

It was kind of scary because we weren't sure how far they would take it. There was only one person that didn't like us, and it was strictly we took away business from them because they forced us to. My mother, the champion of me forever, drove me down to the police station and said, "These guys are hurting my son."

I said, unabashedly, "They're going to kill me. And this is the guy, this is all the owners of this company. If I die, go arrest them. I'm telling you in advance, they're going to kill me." I didn't even know what that meant.

About two weeks later, my tires stopped getting popped. None ever again happened. I suspect that the police went, "Guys, you've overstayed your welcome. We're not going to go after you, but stop it. They've identified you as the guys. If they get hurt, you're going down for it." I made that assumption up, but it stopped the tire‑popping. It was so bad, I knew the tire company by first name. I'd go, "I need four more tires today." They said, "You got four tires yesterday." "I need four more today."

Wow.

Tires were like $20 a pop back then, but $80 a week was a lot of money, or $80 a day.

That's a heavy business expense.

I could have bought a lot more comics for that. That was, to me it was an emotional thing. Like, "Screw the tires. You're impacting our ability to buy more comics."

How did access to new comics change your ability to sell?

To sell them?

Being able to get comics from Seuling. I guess you were already choosing the titles you wanted, but now you're getting a lot better discount. How did that change your business?

Basically, we went from 25% from San Diego Periodicals to 50% off from Phil Seuling. The margin doubled, so we could afford to burn, or not sell, some books and still make equal or more money.

With the excess books, we were starting to wholesale them to those comic book stores and some other swap-meeters as well. Some people were going to swap meets selling comics, and we'd sell them all the excess books, maybe even at our cost—not at a profit, just at our cost—to get our money back. It made our stores more viable because we had every issue now. We weren't missing issues.

Did new comics become a bigger part of your business then, as opposed to the back issues?

It was. Although, in the early '70s, there weren't that many new comics being published, so our sales were 90% back issues. There was almost no licensed merchandise in our stores at all. If you called up Marvel or DC, which I did a couple times, said, "Can you tell me who licensed the T‑shirts from you?" they said, "We don't give out that information." I'm like, "Well, how do I know who to buy them from?" [They] said, "We don't give it out." Sears and JC Penney and the big mass market guys all had Marvel and DC shirts. We knew they were making them for somebody. We just couldn't figure out how to get them.

Our stores are basically print stores, except we realized we could make our own products by taking comic book covers, ripping off the front cover, putting a piece of wood, and decoupaging it. We made, in our stores, actually in the store when the store was open with a torch, we were making our own, unique, unlicensed items because there's nothing to sell.

What about fanzines and undergrounds. Did you carry those?

We did. The two guys that were selling them back then were Phil Seuling and Bud Plant. They had most of that business. Later on, maybe mid '70s, Bud and Pacific teamed up on some items where the minimum order quantity was too high for one of us. We split the production run down the middle.

Really, in the grand scheme of everything, Phil Seuling and Jonni Lavas were so important but really weren't around for very long.

For Part 3, click here.