As the publisher of Star*Reach and later at Pacific Comics, Friedrich crafted contracts that preserved creators’ rights, contracts that set the standard for creator-owned comics at a time when the industry was still in flux.

This interview was conducted as part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

To watch a video of this interview, see "ICv2 Video Interview – Mike Friedrich.”

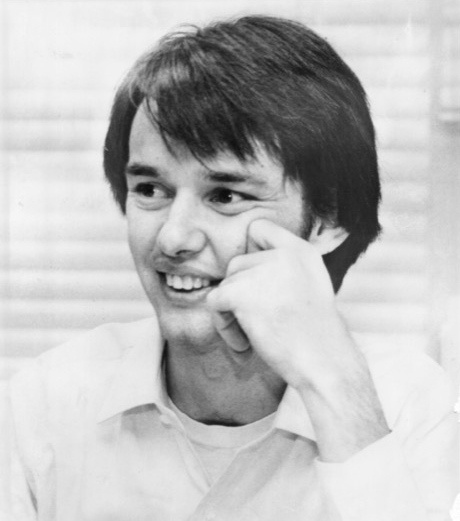

I'm here with Mike Friedrich, an important figure in the history of the comics Direct Market. Let's start out with a little background. You began writing for DC and Marvel in the late 60s, and so were working in the color comic business when Phil Seuling and direct distribution came around (see "Phil Seuling: The Man Who Invented the Direct Market"). What do you remember from that change?

Mike Friedrich: I came to Phil through Bud Plant. When I started the first Star*Reach, I had no real idea what to do with it. I had some background locally from the underground distributors. I just made up a number of how many to print and went and took it to a local convention in Berkeley. Bud Plant bought 500 copies on the spot and clearly air expressed one to Phil. Phil, a week later, gets a hold of me, and says, "I got to have some." From there, it spread by word of mouth. I learned on the fly.

As a comic consumer at that time, did you see any change when Marvels and DCs started to become more available in comic stores in that period around '74?

Change in what way?

That you could buy a #1, the comics you wanted.

That's true. It certainly was a benefit to collectors. The phenomenon I noticed was that whatever day it was that they were getting comics from their local ID [independent magazine distributor], they had lines out the door of people who had to have their comics as soon as they arrived. That's what put the light bulb over my head that there was a market here.

All of these readers were older. They were young adults. They weren't kids anymore, and yet, Marvel and DC were only giving them a small amount of material that they were interested in. I knew the creators from the creative side had ideas that were more oriented for adult thinking than kid thinking. I put the two ideas together.

The term that's used to describe Star*Reach is ground‑level comics. Do you know where that term came from?

Yes, it was actually a joke that Trina Robbins made that given my sense of humor, I thought was pretty funny. She did it as an insult. I decided to use it as a banner. [laughs]

Ground level because they weren't cool enough to be underground? Was that the joke?

Right. They weren't good enough for Marvel and DC. They were in this middle level. They weren't underground comics. They were ground‑level comics.

It helped me brand it as in between (let's just stereotype it) gross underground comics and Conan and X‑Men. You can get the freedom of the undergrounds and the interesting content of the Big Two.

How were your comics different from undergrounds?

Underground comics were largely very personal and cultural, where we were doing action, adventure entertainment, fantasy entertainment.

It sounded like you didn't have a great business plan when you started. Your goal was just to publish the comic?

[Laughs] It was one of those "This would be a good thing to try out. Let's see how it goes. It would be fun." And it was fun.

You were thinking, originally, you would just sell them at shows?

I had no distribution plan. I showed up at a convention, and distribution came to me. You came to me. You saw a copy at some point and you wrote me and said, "I'm Wisconsin Independent News Distributors. We want to buy your comic. How much are they?" So I sold them to you. That's how I was connected to all the distributors. The only distributor I knew was Bud Plant.

Did he explain the 60% off non‑returnable model to you? I think that's what you were selling at, right?

I learned that earlier. I had earlier been introduced to the underground market by a retailer named Bob Sidebottom, who took me around in, I can't place an actual date, but let's say 1972, 1973. I probably made three or four trips up from San Jose to San Francisco, where he would make one stop at the San Francisco ID distributor, where he'd pick up his Marvels and DCs, then he would go to Rip Off Press and Print Mint and Last Gasp. That's where I met the underground distributors. I learned, on the drive, the one‑hour drive in each direction, and in these meetings, how the distribution system worked for the undergrounds. That was my model, was that I would sell them at 60% off to wholesalers, who would in turn sell them at 50% off to retailers.

You also handled the creator's rights a little differently, or a lot differently, than the Big Two were doing it at the time. Can you talk a little bit about that and where that came from?

That definitely came out of the underground experience. That was what almost everyone on that front said they were doing, was that the creators owned their copyrights. They had creative freedom. That was non‑existent at Marvel and DC at the time.

That was the big appeal to the artist, was that I was giving them the opportunity to work in the medium that they enjoyed but to have more ownership and more long‑term reward if they hit the market.

Where did you get your contract language, or how did you develop that?

I had met one of the Wimmen's Comix artists named Lee Marrs, who's now my life partner. At the time, she was a cartoonist that I met. She showed me the contract that she had with her colleagues at Wimmen's Comix and Last Gasp Publishing, and I used that as the basis. I redrafted it to apply to what I was doing, but I'd say 80 percent of it was that agreement.

Do you remember any of your other wholesale customers, other than Bud and Phil? You mentioned Wisconsin Independent News Distributors, the company I worked at, WIND.

This is where my memory gets a little weak. I know the Donohoe Brothers in Michigan…

From Big Rapids.

Right. Pacific Comics down in San Diego.

Were you selling to any of those people that were more underground‑focused or head shops or any of the other kind of stores?

Ron Turner at Last Gasp was a distributor for, I'd say, the first five or six issues, but after I'd been in business for two or three years, the comic market distributors captured all of Ron's business, and so Ron dropped off.

I see. I remember what kind of stores we could place Star*Reach in, and it wasn't the same as Freak Brothers.

Right. There was a little bit of crossover, but not a lot.

You did Star*Reach for maybe five years or so. Would that have been possible without the Direct Market?

No, absolutely not. We were the first publication that was focused specifically on what we now call the Direct Market. Didn't have that term back then. The Direct Market was in formation through what Phil Seuling was doing, and others, to set up with Marvel and DC. Star*Reach piggybacked on that formation but was the first publisher focused on that market, on that distribution channel.

Then, at some point, you stopped publishing and ended up in Marvel, and I think as their first direct sales manager. Is that correct?

That's right.

When was that?

In 1979, my publishing was beginning to get weak, financially. I'd made a couple of bad decisions. I'd started publishing color comics too soon and wasn't able to recoup the investment. Marvel was at this time, and I'm speaking retrospectively, of course, was seeing this market growing, but they didn't understand it.

Their executives were coming out of magazine distribution. They didn't understand the comic market. The then‑Sales Vice President Ed Shukin [and] Jim Galton, who was the president [of Marvel Comics Group], between the two of them, they hired a distribution consultant whose name I've now forgotten, who came around the country (it was Stan Neville, see “SDCC 1979”). He came to Berkeley, and a local comic store owner, John Barrett, said, "You should talk to Mike Friedrich." The guy bought me coffee and talked to me, and I told him exactly what I thought of Marvel, which wasn't much, and told him all the things they were doing wrong and all the things they should be doing.

Three months later, they posted a position for a direct sales manager. I thought about it, and I applied.

Posted? How did they post jobs then?

That's a good question. I don't remember how we learned about it, but it was sent around the Direct Market. It may have been in a fanzine. I couldn't tell you. Jim Shooter would probably have that memory more than me.

I handed in a resume at the San Diego Comic-Con in '79, and they interviewed me in September and hired me a month later, and I started in January of 1980.

You were reporting to Ed Shukin?

Yes.

What were your tasks? What did you do?

My main one was to just make sense of the market. The first major task was to create trade terms that were sustainable, profitable to the company, and, in my view, would build the market. There had been a history of basically anyone who showed up and said, "I'll sell your comics," being allowed to buy the comics, even if they were just faking it. They wound up getting sued. Hal Schuster sued them, and the lawyers of the parent company clamped down on Marvel and said, "Stop creating bad conditions."

I spent the first three or four months drafting trade terms that were basically just enough to let Chuck Rozanski buy the books. That was the bottom line, the size, you had to be Chuck Rozanski or bigger to be eligible to buy the comics.

The company that I was involved with at the time, which was Capital City Distribution, was formed in April of 1980, so we must have been one of the first companies opened under those new terms.

The first thing I had to deal with in the direct market was Big Rapids Distribution Co. going under, which left Marvel holding a very large payable. I knew that Big Rapids was bad news to begin with, so I clearly washed my hands, and I just recommended who were the people that should inherit the business, and you guys were part of that.

They had a bunch of drop ships, so I assume there were more than just us who came out of that collapse.

You're probably right, but I don't remember who else there were.

Talk a little bit about the attitude toward the Direct Market inside Marvel. You said they were trying to learn about it. Did they see it as a positive? How were they feeling about the ideas as this new thing was happening?

It depends on which chair you're sitting in how they felt about it. On the editorial side, Jim Shooter was all in favor of it. Ed Shukin was mixed because he saw the numbers. The numbers were going up, huge increases every month over month. We were growing 30‑40 percent a year in the Direct Market, the years I was there.

He got his fingers burned by getting sued and so was happy to let me take care of it. He got the credit for it, but at the same time, he was concerned he was working himself out of a job, which eventually he did. Jim Galton, the publisher, was a numbers guy who came out of accounting, and he was just looking at, "How are we going to make money?" The non‑returnable aspect of it really appealed to him because it meant these were more profitable than ID comics. In general, he was very supportive. They were willing to support expanding the market.

Their chief competitor, DC at the time, was much more conservative. They were looking at the people going bankrupt. They weren't looking at the profits made at the same time. It took a while for DC to catch up. There was actually very strong executive support at Marvel for building the Direct Market in the early '80s.

I remember meeting with Jim Galton at some point in the early 80s when he was showing some new formats. Marvel Fanfare came out of that, and they had two or three new formats. Can you talk a little bit about how the Direct Market made the change in comic formats possible?

We quickly learned that what we called collectors at the time, young adult consumers, were willing to pay more money for better‑looking comics, so that if we printed them on better paper, they would pay more money for them.

This is, again, where editorial support was key, that they were willing to develop the editorial packages that we could then format, and figure out the best financial format to put them out in. We tried a few different ways of going. What seemed to settle was slightly better newsprint, but not glossy.

I remember, that wasn't Baxter paper—or was it?

Whatever term they used. White newsprint.

How long were you at Marvel?

I was there for two years. I was there on my personal terms. I was there to pay off my Star*Reach printing bill. I was there to save as much money as I could from my salary to pay my printer off and then return home, so I did. I knew that it needed to have good hands, and so I got permission to hire an assistant. I knew that that assistant was going to be my successor, although I didn't say anything at the time.

I was very fortunate that Carol Kalish was on the market for a job. She came on, and I remember telling her the first day she was working that, "By the way, I'm leaving and nobody knows it, so get ready."

She did.

That was one of your more impactful actions at Marvel, as it turned out.

I intended it to be that way. She was really good. I hit it off with her really well. I was very sorry to see her go.

Why did you think she'd be a success at what you were trying to build?

She had the fan mentality and a business head simultaneously, and that's a tough combination to find, but she had it. She was very, very smart, but also hardheaded and cynical. [laughs] If you're a romantic comic reader, you have to become cynical. [laughs]

After that, you formed a talent agency to represent comic creators. Can you talk a little bit about that? Maybe more broadly the whole arc of comic creator rights, and the Direct Market role in it and your role in it.

It's another job that I stepped backwards in without doing any research, but it wound up being the thing I wound up doing the most in comics, because I had my agency for 20 years. I just remember when Frank Miller made his Ronin deal with DC, I said to somebody, "This means there's going to be agents in comics."

Six months later, I became one. I needed something to do. I'd left Marvel and gone and done three months of consulting work for Pacific Comics publishing, with the hope that there might be a long‑term position there, which did not happen. At the end of those three months, I needed something to do, and I think literally on a Thursday I said, "Well, let me try being an agent." By the following week, I had three clients and two projects, and I sold them both, so I was able to get started.

Who were you representing your clients to? Marvel and DC, or other publishers?

Marvel and DC, initially, were background to more of the emerging publishers like Pacific Comics. Dark Horse Comics came along pretty quickly. Eclipse Comics. I remember Pacific and Eclipse were my first buyers.

Marvel had their Epic Comics, and there were creator‑owned comics. I sold some stuff into Epic. DC, eventually. I migrated into representing people who did the work‑for‑hire work on their pre‑existing characters. That was a few years later. The initial stuff I did was all creator‑owned material.

Has there been progress of creators in terms of their ability to retain control and ownership from the beginning of your career to now?

The big shift was the emergence of Image Comics, which combined professional distribution and creator‑owned material. Now, an artist (or talent, we'll call them talent) has the ability to take a gamble on their own work and own their material, or take a guaranteed paycheck and work on Spider‑Man.

That's all I could ask for. The full range is there. Especially, the relatively recent emergence of the graphic novel publishing field has further widened the options for people to work in the business.

I'm quite happy to see that the market has become what I dreamed it would be 50 years ago.

Then, you had one other important role in the comics business, which was you were involved in starting one of the major West Coast shows, which is still running today, WonderCon. Can you talk a little bit about that?

To answer that question, I’ve got to back up. I started doing distributor‑retailer trade shows, which failed. I then thought of starting talent trade conferences, which had an initial success, but that failed.

At the tail end of it, I was telling my local buddies (I'm remembering especially John Barrett from Comics and Comix), "I'm not going to be able to do my talent trade shows anymore." He said, "What if we were to tie them to a comic show, a convention?" I said, "Sure."

I worked with John and a bunch of other people to create WonderCon in order for me to have this talent conference, to launch it off. The talent conference was a success as a conference, but financially, it wasn't successful. But WonderCon itself was successful.

By the second year, there were four people that were partners in it. I was one of the four, and I stayed with it. We did it for about 10 years together, and then two of the partners left, and Joe Field and I did it for another five years before we sold it.

To San Diego Comic Convention?

They ran it in the Bay Area for two or three years, and then moved it to Southern California.

You talked a little bit about the creator rights changes, and how that progressed over the past decades. In terms of distribution or access to comics, what are your reflections on the changes that the Direct Market has brought to the reach of comics to audiences that we haven't seen since the 40s or early 50s until now?

The distribution system supports comics specialty stores, which themselves are destination stores for readers that are reliable. The change from when I started in the business over 50 years ago, 60 years ago to today is that there's now a reliable place you can buy a comic in your local market. It's going to vary from region to region how many stores there are.

If you are interested in comics, you know where to go, where 50, 60 years ago it was much more hit‑and‑miss. It was more impulse buying in the past. Now, it's because you want to read comics. That's, to me, an improvement.

For sure. All right, thanks very much. Anything else you want to reflect on in terms of your role in the history of the direct market?

I take the most pride at Marvel and guiding them to setting up sustainable distributors. You were one of them. Steve Geppi was the other one. He came out of the New Media/Irjax bankruptcy. I had met the Schuster brothers’ sub‑distributors, and Steve had impressed me. I was in a position to support the people that I felt could sustain the business. Now, I didn't know that Steve Geppi would take over the business. [laughs] I never saw that, but I knew that you guys were good. I knew Steve was good. I am glad I was in a position to help make that happen, which is something that nobody writes about. [laughs]

Then, on the creator rights side, too, I think you had a big impact. The market owes you a thanks for that as well.

There was a tiny little slice in the middle there: what I did in those three months at Pacific Comics was help them draft their publishing contract with their talent. I used my own Star*Reach agreement as the basis for it.

For 20 years after that, people would show me the Pacific Comics contract, and say, "This was the model we used." I took some pride in that. It, of course, pushed DC and pushed Marvel to open up their terms as well.

Pacific signed Jack Kirby, right?

Right, yes.

Big get. [laughs]

Yes.

The biggest. Thanks very much. Really appreciate it.

Good. I'm glad to have the chance to chat.

Click Gallery below for photos!

View Gallery: 3 Images

View Gallery: 3 Images