Paul Levitz had a long career at DC Comics, starting out as a freelancer when he was still in high school, rising through the ranks to President from 2002 to 2009, and retiring in 2010. During that time he had an active hand in shaping the Direct Market as well as the comics sold there. Part 1 of this interview focuses on Levitz's early years, starting when he launched a fanzine at the age of 14 that brought him into contact with creators, retailers, and Direct Market pioneer Phil Seuling. In Part 2, he talks about the rise of the Direct Market in the 1980s and how DC tailored its content for this new audience, leading to the creation of the Vertigo imprint. In Part 3, he discusses how Image Comics changed contracts with creators, how Marvel Comics' purchase of Heroes World changed distribution for DC, and how he thinks comic shops will evolve in the future.

To watch a video of this interview, see "ICv2 Video Interview – Paul Levitz, Part 1."

This interview and article are part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

ICv2: I’m here with Paul Levitz, who had an amazing, long career in the comics business. We're going to talk about his history as it relates to the growth of the Direct Market, in which he played a huge role.

You started in the comics business at a very tender age—which, I think, was fanzine publishing. Can you talk about that a little bit?

I was one of the tail end of the first generation of comic fans who were specifically comic fans. At that point, there were a few fanzines being published, but the only one that really was being published with any regularity about news about what was coming out in comics was Don and Maggie Thompson's Newfangles.

This is early 1970s, and publishers weren't announcing in advance when the next comics were coming out. There was no TV Guide for the field. An awful lot of the material was being published without credits.

Don and Maggie were a young married couple, happily married, producing a couple of kids, having lives, and doing a fanzine that was not a profitable proposition, wasn't intended to be a profitable proposition, was kind of a drain. They announced one day in January of '71, "That's it. We're going to give up at the end of this year. If you’re a subscription, we don't want to return any money, so we're going to keep publishing until the end of the year. If your subscription runs out in between, you can send in the money for the rest of it, but nothing past December of '71. Thank you very much, everybody."

My buddy Paul Kupperberg and I are sitting around my parents’ house, "Oh, my God, we're not going to know anything." We throw together 16 bucks between the two of us, and we start a fanzine with the goal of being basically the TV Guide for the industry.

At that point, it's a very small business. There are maybe 200 creative people working in comics in America. Something like 95% of them are in the New York metro area. There are only five or six publishers. depending on how you want to count it.

This is long before 9/11, so you can pretty much knock on the door and get in with any reasonable excuse to visit places. We start calling DC and Marvel, get some propaganda from them, and play boy reporters. Kupps drops out after a couple months; I stick with it.

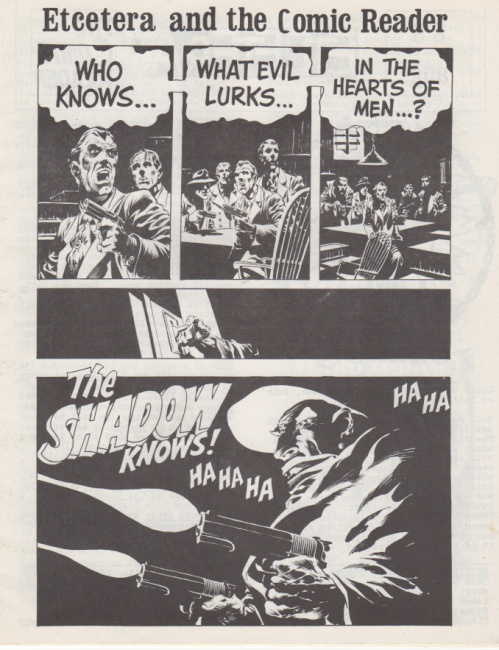

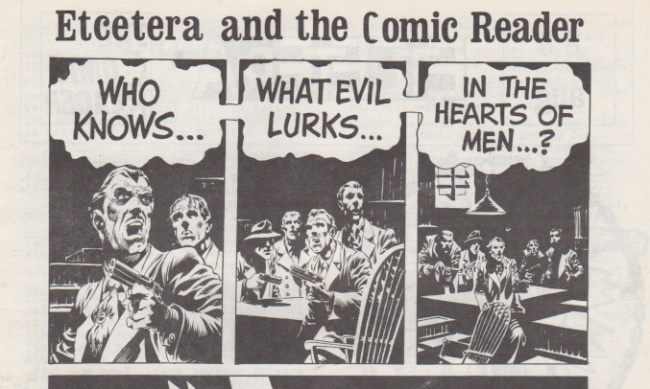

Mark Hanerfeld, who had published the last TV Guide for the field, something called The Comic Reader, comes up to me in the DC offices one day, literally with a manila envelope full of coins and index cards, and says, "You're doing what I set out to do and I don't have the time to do it. Why don't you take the subscription money that I've accumulated and the subscribers and add them to yours and you do it?" So I became the editor of The Comic Reader. We combined that with our existing title of Etcetera, and that then was one of the two or three largest circulation fanzines about comics, and by far the largest circulation one that offered any news about the field. I'm 14 years old. This is a cockamamie little act of entrepreneurship, and I end up needing a checking account and having a business that was actually making a profit.

How did The Comics Reader get to its readers?

Mail subscriptions. You've read something about it in another fanzine. You read something in a plug—occasionally the comics would feature something, writing up about it. People would see a printed address in the letter column and send a sample copy of a fanzine, and we sort of all connected through all of this. Ads in the couple of ad fanzines that were out, The Buyer's Guide in its original incarnation, something called the Rocket's Blast Comicollector. Those were places mostly where people advertised "I have Avengers #3 for sale for two dollars in mint condition, would you like it?" I'd buy a full-page ad.

If you look at any of those early fanzines that I did, God, they look horrible by modern standards, because we were way before desktop publishing. These were little flimsy things, but the professionals in the field got a kick out of it because it actually told them when their work was coming out and gave them credit for it, which they often weren't getting. They were happy to provide information and gossip about what was going on. The publishers were usually pretty benign as long as we kept the things secret that they wanted secret at any given moment and didn't attack them.

By the time I was finished with it when I was 16, the circulation was up to 3,500 copies a month. A handful of the early comic shops like Supersnipe here in New York, Village Comic Art in New York, Bud Plant, were taking bundles of 25 or 50 copies and selling those at retail, or trying to sell them at retail. I began to be connected into the web of how all things work.

Those stores that you mentioned, those were pre‑Direct Market comic stores, right?

Yeah.

How were they getting comics—or how were you getting comics?

Mostly the stores were getting them from the ID Distributors, the distributors who serviced the newsstand. In many markets, the ID distributors operated what they call the cash table, where they would literally put out on a handful of tables the comics and magazines that they were offering for sale on a wholesale basis, and you could come in and pluck them off.

Certainly in New York, it was possible to do that. That was how Village Comic Art or Supersnipe and the other couple of shops that we had were doing it. I was aware of that. People did it every different way.

I know you did an interview with Nick Landau [of Titan]. Nick became an early friend, and I remember buying copies of Shazam! #1 at retail off the local newsstand to ship to him in England for him to resell over there. Fans were an entrepreneurial, enterprising and very dangerous group.

Then at some point, a comic convention arose. What was the first comic convention you went to?

Pretty quickly after I started the fanzines, it was the '71 Seuling con. I knew Phil. My dad had actually rented him a store when Phil briefly went into the retail used book and comic business in Brooklyn. This is probably, I think I was in junior high school, so this would be '68 or '69. It lasted about a year, maybe two years.

My dad did some sideline real estate agent work for a cousin who had a real estate brokerage. I had met Phil and Carol and their kids. I was a kid myself, obviously, in those years and had gone to the shop any number of times. Phil invited me to not only go to—I was not only going to the convention, but I was going to have a table at it, what Phil called his fanzine table. He gave me the table free as long as I would sell my fanzine and other people's fanzines and give them the money that came from it. I began doing that as a little side business as well for the next few years.

When you were selling those fanzines at the table, those were things like yours and Rocket’s Blast and similar publications?

A lot of things that were done by people who would end up going on into the field or who would be early, passionate fans of it, who would put out one or two fanzines and then give up. Fantazine by Marty Pasko and Alan Brennert, two wonderful writers who became dear friends of mine. David Kasakove, who was a big EC fan, did one. Neal Pozner. Bob Greenberger.

Then at some point, Phil went into distribution. Did you hear about that at the show or elsewhere?

I start doing freelance for DC when I'm in high school. I start doing letter columns and text pages for them, and that makes me their mascot from fandom, for probably lack of a better term.

I'm in the offices one afternoon working on one of these things and Sol Harrison, who was the VP of Operations, I think was his title in those years, comes over to me and says, "So, Phil Seuling was just in, and he has this idea for distributing comics right to the comic shops. Do you think this will be a good idea?"

"Yeah, Sol, sounds good to me."

I don't remember how long the conversation lasted or how accurate it was as to business logic anywhere in there, but this was the beginning of Phil doing it.

The first summer that Phil was doing this, he hired me to be one of the people working from the front porch of his house, working on the paperwork of the early direct distribution. He was completely overwhelmed by the business he'd gotten himself into. It was very different than what he was used to, and he was still teaching English at the time. Still going in technically as an English teacher, but no longer allowed in the classroom at that point, I think. It's hard to make synchronicities work.

What was the attitude inside DC? You said you were the fandom mascot, so they were aware of fandom. What was the attitude of the people inside DC? You said on the creative side they were supportive. What about the executives like Sol?

I think Sol generally was very supportive of the idea that they were these kids who loved comics. The dichotomy in the offices, I guess can be summed up by, it's all very nice and good, but these aren't our real customers, so let's not get distracted too much.

The older writers and artists often were very frustrated by the loud voices of fandom because the fans were older than the core customers. The business of DC Comics really was selling to 6-to-10-year-olds, 6-to-12-year-olds, and the early fans were 12-to-20-year-olds, even in some cases like Don and Maggie, grown human beings, adults with families and jobs even. Their tastes were different, and they'd get all excited about a Neal Adams art job or a Denny O'Neil story. They'd say, "This is terrific, I bought two copies, I bought 10 copies, or my store bought 10 copies and they sold right out."

The attitude around the office was, "That's nice, but we sold 100,000 of them over there to the kids. We're in business to try to sell large numbers." Superman was still selling, by that time, probably net 250,000 copies maybe an issue. Fandom represented on a successful DC title, if you could identify it, 5,000, maybe 10,000 copies if you could pull it all together.

There's no decent statistics from that time about it before we get to the Direct Market. There's a lot of back‑and‑forth debate on the websites or Facebook or wherever, where Bob Beerbaum will recount a story of how many he bought in San Francisco and try to extrapolate from that to a national number. Maybe, maybe not, but certainly the executives were not taking this as a serious part of their business yet and wouldn't for many years.

One of the early retailers I interviewed thought that he had seen something about Sea Gate as it was being formed, read about in The Comics Reader. Did you talk about it in the fanzine?

It's a good question. I don't think so. I'd have to go back and look at the last few issues. I think, as a distribution company, it's just coming into being as I'm going out of business.

How did shopping for comics change after Phil started selling comics? Did Supersnipe or Comic Art Gallery, were they buying from Phil, and did that change what you were seeing in the stores?

Pretty much anybody who had a significant comics business shifted over to buying mostly from Phil. The pricing was better. The cash tables would have been a good secondary source because you could buy later from them.

The downside of the early direct model as the company set it up and as Phil set it up, at the beginning both DC and Marvel required payment in advance. I think the smaller publishers did as well, and in advance of printing the damn thing. These tiny little comic shops were essentially buying on negative 90‑day terms. God knows how they found the cash to do that, but the ability to go in the week before you would believe you would be selling the goods and get more of them from a cash table probably was a very significant cash management tool for most of them at that stage.

Over time, Marvel would go to decent credit terms for the Direct Market by the late 1970s. I'm not sure when that shifted over. DC wouldn't until my tenure in 1981, until my tenure on that side of the company. I don't remember when the early direct distributors began to offer that kind of credit terms down through the system to the individual stores.

What was it like walking into a comic store in the '70s? What were they like?

Very small. Particularly in New York. Supersnipe was on the Upper East Side. The retail selling space was considerably smaller than this room. On Saturdays, you queued up outside the store and waited for somebody to leave to get your stuff. Village Comic Art probably was a little bit larger but in worse retail space, it wasn't on a block anybody would casually walk by ever, on Morton Street in those years, so it was definitely destination shopping.

Did they have racks or boxes or how did they display comics?

Most managed to get racks. You're in the years when the Comics Magazine Association was fairly energetically funding rack programs through the newsstand distributors. If you went to Brooklyn News and said, "Can I get one of those comic racks?" Brooklyn News would be thrilled to sell it to you and probably have a few in the back room to work with.

Usually the waterfall racks were the most common thing. I think Village Comic Art had regular shelving, but nobody had anything custom.

I've been told, and I remember you talking about it at a panel in New York, at New York Comic Con, that conventions changed the interaction between fans and creators. Can you talk about that phenomenon?

If you take the path of what the creative mood was in comics when I came into the field in 1971, you had two generations wandering around. You had guys who had come into the field anywhere from the very beginning of comics to probably having come in at the end of the Golden Age or the very beginning of the '50s. There were only one or two people at any comic company who came in in the 1960s. It was a time of musical chairs, and the chairs kept getting taken away, so there weren't many new ones for new people to come in.

Towards the end of the '60s, you began to have this younger generation, Mike Friedrich, Jim Shooter, Len Wein, Marv Wolfman, Denny O'Neil, names people who will recognize, who started to come in, mostly from (Roy Thomas) from comic fan backgrounds.

The older guys, and it was virtually all guys (two women creators working in the field in those years), were very suspicious for the most part about this fan culture. On the other hand, they were pleased that somebody cared about their work.

The dramatic change over the years was as the conventions got larger and the people attending them got more respectable looking, the older creators began to look and say, kind of Sally Field moments, "You really love us? You know who I am? I never even got to sign my work and you're telling me you know all this about it?" That was a wonderful moment for a lot of them.

Then in the mid '70s, DC made what seems in retrospect to be a surprising hire of publisher, bringing in Jeanette Kahn. How did you become aware of that change, and what was going on at DC then?

Well, Carmine was fired. Carmine Infantino, the artist who'd been moved up through the creative ranks to run the company for about a decade under a variety of titles. None of us had any idea who Carmine worked for other than it was Warner Communications. His style was not to personalize the management team that he reported to. It was just, "I got to go upstairs for a meeting tomorrow."

So Carmine's fired. Of course, no one knows for sure why or what's going to happen. Everybody's kind of wandering around wondering what's going to go on.

We're summoned into the little conference room DC has. Again, it's a very small company. There were about 30 people working for the company at that point. This really tall guy comes in, taller than you, I think, Milton, and introduces himself as Bill Sarnoff, the chairman of Warner Publishing, whatever Warner Publishing is. We're not entirely sure of that. I was probably one of the few people who was interested enough in business that I knew it existed.

He says, "It's OK. We're happy with DC. Nothing bad is going to happen. We're going to bring in somebody new. We don't have it settled yet, but we'll introduce it in the next couple of weeks. Sol will watch over things in the meantime. Just keep doing what you do." He disappears. A couple of weeks later, he pops in once more to announce that Jenette Kahn is arriving as our publisher. Sol will now be president, she'll be publisher. They will be equal and they will share the management of the company.

It's like a Martian landing. At that point in the history of the field, I don't think an outsider had ever been appointed to run one of the major publishing companies. The only woman who was in charge of a comic book company was Helen Meyer at Dell, which had been out of the business for quite some time. She'd been invisible to the fan side of the business. That was when Dell was not just a comic book company, but a children's publishing company across a number of different things.

There were no women in any positions of responsibility at DC or Marvel in those years. Or, well, there might have been one at Harvey. There might have been one editor at Harvey. I'm forgetting her name.

She [Kahn] was 28 years old. 28 years old! If she'd been green and had antennas, she wouldn't have been any weirder. She descended on us. She had an extremely successful background in children's publishing. She'd created the magazine Dynamite, which was a real cash cow for Scholastic in those years. Before that, she'd done something called Kids magazine, an early magazine done by kids for kids. I think she was still in college when she did that. The company viewed comics as a kids’ magazine business, so this was not implausible by management’s standards.

It was a somewhat awkward structure of power sharing between the two of them, because they had very little in common other than the fact that they were both Jewish and basically really good human beings. Sol's style was to come in early, leave late, keep his door open throughout the day, and if you need any help, come on in and we can talk. Jenette operated often behind closed doors, threw parties for the creative talent at her own home, and did business wherever she went in whatever connected fashion she did. If you had a meeting while you were having lunch, or while you were having dinner, or at a party, or while she was having her nails done, you just made it work.

I was 19. I was optimistic about it because the comic book business was in the death throes of the newsstand business model, it was very clear, and here was at least somebody young with a new point of view. I very quickly saw that she was smart as hell, asked great questions, was thoughtful about the business, believed in the power of comics, didn't know the comic book business well but had read them as a kid and understood things that we needed to do instinctively very quickly.

We worked wonderfully together. Within about a month, I had an opportunity to go full time. Up to then, I'd been a part‑timer in the place on a per diem deal and went full time as an editor, dropped out of college. We had a load of fun for the next 25 years together.

Who was running it? Was Sol handling the distributors at that point and Jenette was creative, or what was the division between the two?

It was a little bit fuzzy. Basically, Sol was responsible for the licensing side of it, the physical production department. That's the world he grew up in. He was one of the first color separators on comics and had grown up through the production side. He was handling the responsibilities for the Direct Market and the ID market predominantly.

Jenette was predominantly responsible for the creative. Obviously there had to be some overlap. In a perfect world, there would have been some greater collaboration. Sometimes it happened, often it didn't.

You were on the creative side. How aware were you of what was happening in distribution in the late '70s?

Well, I was on the creative side, but in many ways, I very quickly became the business guy on the creative side, working on the contracts. Sol also was very friendly with me, and I went to ID conventions. I went on visits to the ID distributors. I attended the print order meetings that we did on the ID side as sort of the creative representative to the business decisions. I'm a punk-ass little kid at that point. Nobody's taking me too seriously. My knowledge base is fairly limited, but I'm getting visibility into all of these pieces and learning and absorbing.

I want to ask about both sides of that. What was an ID convention like?

You'd be down in Mexico, and a bunch of guys playing golf and drinking and playing poker with each other, and a few little presentations by the different distributors to the newsstand business about how wonderful these distributors were, and how terrific the magazine business is, and we're all, "We should all work together and have a good time."

What about on the direct side? Were you meeting the direct distributors other than Phil by that time?

Not until later on. Some of them I knew because of my own fanzine. I knew Bud from back in my fanzine days. I knew Chuck [Rozanski] very early on. Maybe one or two of the smaller ones who were handling, who had grown out of their own shops, so it's possible somebody like Joe Krolik in Canada, but there were no distributor meetings yet at that point.

I remember a trip to, and I in fact found notes from it recently, a trip to New York with Jim Kennedy. We met with Sol Harrison. Must have been about '78, '79. I don't know if we even knew who Jenette was, but Sol was definitely the face of the company to direct distributors at least as far as I was aware.

Click here for Part 2.

On Fanzines, Early Fandom, and the Beginning of the Direct Market

Posted by Milton Griepp on October 6, 2023 @ 3:08 pm CT

MORE COMICS

From Marvel Comics

August 19, 2025

Following X-Men of Apocalypse Alpha #1 next month, Jeph Loeb and Simone Di Meo's epic Age of Apocalypse sequel series continues this November in X-Men of Apocalypse #1.

Remastered Paperback Edition of Eisner Winner with New Content

August 19, 2025

The digitally remastered edition of the Eisner-winner includes new content.

MORE NEWS

New Post-apocalyptic RPG Based on the Board Game

August 19, 2025

9th Level Games revealed Thunder Road: Vendetta RPG , a new post-apocalyptic RPG, which has hit preorder for retail.

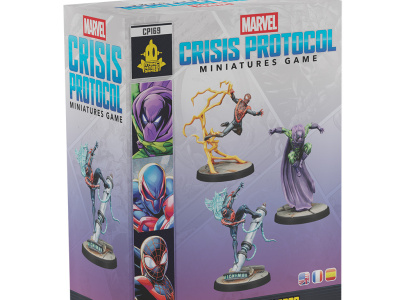

For 'Marvel: Crisis Protocol'

August 19, 2025

Atomic Mass unveiled two new Spider-Man Character Packs for Marvel: Crisis Protocol.