For this part of the history of the Direct Market, we are turning the table and letting comics historian Dan Gearino, writer of Comic Shop: The Retail Mavericks Who Gave Us a New Geek Culture, interview ICv2 CEO Milton Griepp about his days at the helm of Capital City Distribution. Griepp and his partner John Davis started Capital City in 1980, and it grew from, literally, two guys and a truck to become the largest comics distributor in the U.S. In Part 3, Griepp talks about Marvel Comics' decision to self-distribute and the chain reaction that started, which ultimately led him and Davis to sell Capital City to Diamond in 1996. Part 1 focuses on Griepp’s early days working for a Wisconsin distributor of alternative papers and underground comics that was swallowed up by a larger distributor with a very different culture and ultimately went bankrupt, leaving him and Davis to strike out on their own and create Capital City. And in Part 2, Griepp discusses Capital City's years of growth, as it adapted to a changing market and introduced innovative practices to comics distribution.

To watch a video of this interview, see "ICv2 Video Interview – Milton Griepp, Part 3."

This interview and article are part of ICv2's Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

Dan Gearino: We were at a point now where Capital City and Diamond are these two giants, and this is we're almost in the heavyweight fight portion of this long history of distributors, right? Or how would you describe it?

Milton Griepp: I was saying that it became more and more difficult for the smaller distributors to compete with the larger distributors, because there were huge economies of scale in the moving of product from place to place and packing product and the ability to market.

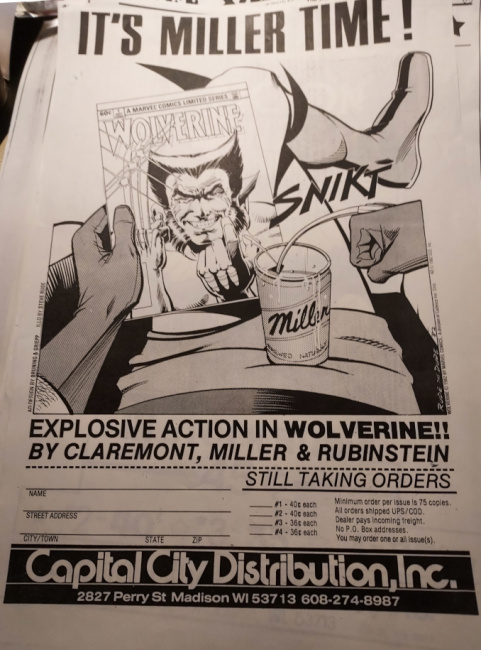

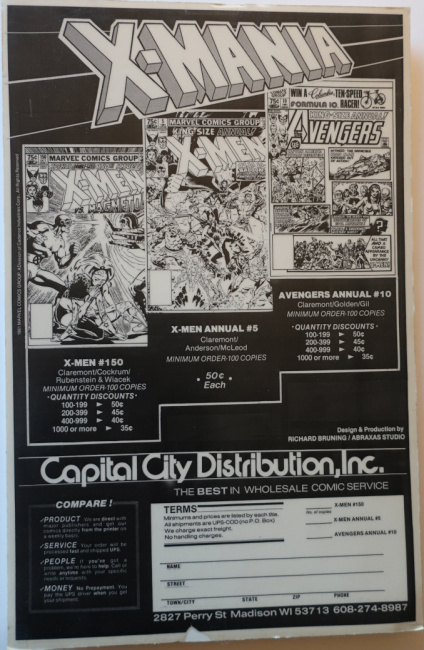

One other thing I should talk about is the publications, which you asked about a little bit ago. There was a key individual in that process. His name is Richard Bruning. He and I did a lot of the work. We advertised in Comics Buyer's Guide a lot, multiple pages an issue. That was a weekly. He did all the designs. He became senior vice president, creative director of DC Comics and was a very talented designer. He also designed a bunch of our publications. I should really mention his role in doing that, because marketing became a key differentiator for Capital City. With scale, we could do more with marketing than our competitors could.

Those publications just look so good. You look at some of the other things that were coming out, other magazines and things that were coming out at the time, and a lot of them were pretty clunky in terms of their design. Internal Correspondence in its heyday looked so nice.

Oh, that was Richard. He was a fantastic graphic designer. Right now he's doing design for Berger Books, the Dark Horse Comics imprint. Super, super talented guy.

We're in a world then where the comics market is going great, we're in the post-Batman 1989 heyday and Capital City and Diamond are these two giant companies competing with each other.

Of course, we didn't realize it at the time, but we were heading toward this car crash, which is Marvel deciding to self‑distribute. Give me an idea of right before that, right before it was clear that Marvel was going to blow up the market, what was it like? How would you describe those days?

'93 was a really pivotal year in a lot of ways. That was the Death of Superman, which was a huge international public relations event for DC Comics. Everybody sold kajillions of that. Image was becoming very successful at publishing. There was an upstart called Valiant, which is still around in a form, that was also becoming very successful at publishing comics for the Direct Market.

There was this explosion of content for the Direct Market. The merch side of it, which you alluded to when you were talking about the Batman movie, that was in 1989. We were getting trailer loads of Batman merch in: sneakers, t shirts, cups, every kind of merchandise. That was a revelation that, "Oh, comic stores can sell all of this branded merchandise as well." All of that aspect of the business was also expanding very rapidly.

'93 was a key tipping point in the sense that there came a couple of phenomena that combined to really harm the market. One of them was an excess of product. There were more and more products being produced, and they were being produced more rapidly than the market could grow to absorb them. Comic publishers were shipping product late, later than scheduled. Image Comics was the worst at that. That's harmful when the market is shifting because since comic stores are buying non‑returnable, if their orders don't match what the market is when the books come in, they can get stuck with inventory, or they can not have enough. The former of those was happening a lot by the end of 1993. Image would put out an issue of a comic and everybody would say, "Oh, that's really great. I’ve got to order more of the next one." Then it would take three months to come out, and by the time it came out, people would be less interested. Retailers would get stuck with inventory, couldn't pay their bills. We'd get stuck with inventory. The whole system was starting to clog up with excess inventory, which means money was sitting in places that the inventory wasn't getting converted into money. That became sclerotic for the whole system.

Those were very difficult, damaging changes. DC did a Return of Superman, which was less successful, but people ordered a lot. It didn’t sell through as well. There was so much product being put out by the big two that the quality was declining.

There've been all these periods, when the market ebbs and flows and people ascribe it to external or some kind of meta factor, but it always comes down to what's between the covers. If there's good stuff between the covers, people will buy it and spend money on it. If it's not that good, they won't.

There was just a bunch of product coming out then that wasn't as good. It was very difficult for the market. At the same time, we were adapting to this much increased scale. In 1993 we did $153 million in sales. We had 700 employees. We had 22 locations. All of this was happening as we were adapting.

We installed a new computer system, and although the benefits of that were dramatic, the transition was extremely difficult as it always is in that kind of a big technological transition. There were mistakes and problems and issues. I was in Puerto Rico for a Marvel sales meeting, and our new computer system was getting turned on while I was there. I remember getting a call that said invoice printing is going to take three days, and the software company says it's the hardware, and the hardware says it's the software company. I had to get on a plane and go back and fight our way through that. There was just a lot going on in an extremely complex environment.

We had 700 employees because we were handling all this inventory and all these problems, but that's not a profitable reason to have 700 employees. It was difficult. We did make money in '93, but it was a difficult year.

Marvel would have been your largest supplier then, right?

Yeah.

Your largest supplier, in a move that we can now tell in hindsight was a horrendous mistake on their part, for their own business interests, they decide they're going to self‑distribute essentially. How did you hear about that? Did they phone you? How did that work?

I think somebody else called us first. Might even have been Steve, I don't remember, but I think we heard it from somewhere else first that they were acquiring Heroes World. [Marvel] was owned by Ron Perelman then, who was a rapacious billionaire. Their affinity for the comics business was really financial in nature. They didn't understand the business that well, and they certainly didn't understand distribution. It was immediately obvious this was a huge problem.

This is a gigantic problem for you at Capital City. It's a gigantic problem for Diamond. It's a big problem for all the comic shops. What were some of the immediate steps after that? Was it a panic? What did you do?

We sued. There's this little law called the Wisconsin Fair Dealership Law, which I believe was designed to protect gas stations from being cut off by fuel companies that wanted to open their own gas stations. The wording of the law allowed us to sue Marvel for damages. The previous legal interpretation of the law allowed us to sue for damages in all 50 states, not just in Wisconsin. Very powerful law as it had been interpreted up to that point.

We sued, saying, "You can't cut us off." We eventually settled with them and extracted a pretty significant settlement that allowed us to cover some of the costs of the transition to being a smaller company and not having Marvels anymore.

Were you in touch with Steve Geppi and Diamond during this period? On one hand, you guys are intense competitors, but on the other hand, you guys are getting screwed by the same company. What was that interaction like?

I don't remember specifics, but I do know all of us were in the same boat, so we were all talking about, "Is there anything we can do to get even?"

Then what happens next? The first step here, I think, is Marvel and Heroes World, and then there's several other dominoes to fall after that. What was the next big one?

There were multiple tracks on which we had to run the company. One was, immediately downsize because 20-30% of our business just got wiped out. That required massive transitions, huge human resources planning, accounting, doing modeling, working with our suppliers. That was a huge amount of work internally in the business. Then externally, it was, what are the rest of our relationships like?

It soon became clear that DC was concerned that Marvel would gain a competitive advantage by having their own distributor and was looking at how to do that themselves. They came out for a visit. They were talking to Diamond. We knew we were the two primary companies that they were talking to. Diamond had an advantage because they were about 50% of the business. We were maybe in the low 30s, and so there was less risk in going with Diamond because they were only risking losing 50% of the business. With us, they were risking losing 65% or 70% of the business, so we were at a disadvantage.

We were more advanced technologically, felt like we had a better management team, but DC ended up going with Diamond. They notified us two days before our sales conference was to open in Chicago. They were supposed to be an exhibitor there, notified us they would not be attending. Oh, and by the way, we're cutting you off as of, whatever the date was, and you're on your own.

We had to go into this meeting with hundreds, perhaps as many as a thousand of our retailers there and explain to them what was happening and how we were going to survive, what our role is going to be in the future, and we had to do it all in 24 hours.

What was that 24 hours like?

No sleep. Or hardly any. I got a couple hours sleep that night, but basically, I was going to do a presentation and I had to rewrite everything. The tenet of it was that the importance of these big publishers is declining anyway. We can be a very important supplier. These other lines can be more important to your future and Capital City is going to be here to help you with those.

Now, I don't want to completely gloss over the remainder of Capital City's existence as a distributor, but how many more years after that was it before the company was sold to Diamond?

Two years. Heroes World was '94, and we sold out in mid‑'96. I talked about the transitions. We wiped out hundreds of employees. We totally revamped our entire logistics network. We closed like 20 locations. Massive, massive change on a huge scale. There was also a lawsuit against DC in the same period, which also extracted a settlement, which helped pay for that transition.

Did John go to work for Diamond for a while after that? Did you work for Diamond also? There was a period though where you guys came over after the sale, right?

I did not. The relationship was structured as part of the payments for a consulting relationship, but they didn't really consult with me. It was more just a way to do part of the payments. John and several other of our employees, including Tom Flinn, employee number one, went to work for Diamond in a little office here in Madison and had specific functions they were doing. One of them was the suppliers that Diamond hadn't had. Flinn was helpful with that, especially the international suppliers and then the international business. They didn't have much international business. We had a lot, both ways, importing and exporting. Then John helped them with customers and so on.

I've interviewed a bunch of retailers that were Capital City customers over the years, including one of my favorite stores is DreamHaven in Minneapolis and Greg Ketter was a long-time Capital City store. One of the things he says is basically, in this kind of distributor competition that ended with Diamond as the last one standing, it's like the wrong guys won. It's like Capital City was so much more innovative, etc.

Of course, you're not an objective observer of this. When you look at that whole period and you look at the chaos and then how it ended with Diamond being by far the biggest, do you have misgivings, or do you have a zen about it? What do you think?

Diamond's been successful for decades since. You can't say they were a bad company or weren't good at what they were doing because businesses don't survive unless they're good at what they're doing. From that perspective, it certainly wasn't a disaster for the comics industry.

Steve's heart is totally in the place of wanting a successful comics industry. He's made a lot of decisions about how to do that. One of his decisions was to acquire Capital City. We were on the ropes, and he could have just waited and see if we’d die and then pick up the pieces. Instead, he made it a point to acquire the company, try to have a smooth transition. That was better for the retailers, better for the publishers. Publishers' debts were all satisfied, and the result was much better for the industry. He didn't have to do that. He did that because he cared about the business as a whole. The fact that he's the guy running this distributor that had pretty much exclusive reign over the comic store market, the fact that Steve, his heart was in the right place, he had solid management.

After we did it, Steve liked the idea and he brought in two outside accountants, Chuck Parker and Larry Swanson, to help him run his company. They were very effective managers in terms of the financial side of the business. It was a well‑run business, and I have an appreciation for the fact that they've been able to go as long as they have and be successful.

On the other hand, what was lost in the decisions that were made, especially DC's, because Heroes World was a horrible distributor, and if DC had just waited things out, they would have collapsed and Marvel would have had to return to probably distributing through multiple distributors again. In fact [Marvel] did give up on Heroes World and self‑distribution fairly quickly. Our last pitch to DC was, "You don't have to do anything. You can continue to sell through multiple distributors. All those multiple distributors will be united to support you and oppose Marvel, put you in a better competitive position, and that's your best possible outcome."

I interviewed Paul recently on this question (see “ICv2 Interview: Paul Levitz”), and his argument was that "Well, we needed the data. It was so opaque dealing with multiple distributors, not really knowing what the market was doing. We felt Marvel would have a competitive advantage on the data."

That may be true, but what was lost was that some of that vibrancy and innovation and sources of growth that came from the competition between distributors that had been so effective over the previous 15, 20 years. That was a big loss for the industry.

It seems like people that make things, companies that make things, intellectual property things, want to get as close to their customers as possible. What happened with Marvel and Heroes World, even if that had been reversed for a time, maybe we would have ended up in the same place today anyway, but I certainly think that some things were lost in that change. Obviously, we thought we would have been a better choice.

Two last things. One is, we've had this tremendous upheaval in the distribution of comics recently. Both as someone who covers the industry, but then also with your personal experience going through upheavals in the past, you have thoughts, I'm sure. Where are we right now in this whole process?

First of all, how we got here was all related to COVID. There was certainly some dissatisfaction with Diamond from the big two publishers and from other publishers just because of the stasis situation that the business was in. Hadn't been a lot of change, a lot of innovation. Publishers, I think, felt like there was more opportunity for growth with more aggressive management at the distribution level, but I don't know that any of that would have blown up if not for COVID and Steve's decision to shut down Diamond for seven weeks.

That immediately demonstrated to his publisher clients that they had no alternate means to get to the marketplace, that everything relied on that one person's decisions, and that his decisions weren't always going to be the ones they liked.

DC reacted the quickest and said, "We're going to immediately open other distributors and try to reach the market other ways." We got there basically because of that single decision.

I did call Steve after the Marvel movement to PRH and said, "Hey, I'm probably the only guy out here that knows what your day is going like, or how this feels to have this happen. It's too bad." I commiserated a little bit. It's not a great feeling, obviously, to have some of your biggest publisher clients tell you that they no longer want to do business with you.

As far as where we are now, I don't think the change is anywhere near over. This attempt to vertically align a publisher and distributor, each of the three companies that are now distributing comics have lacks, or reasons why I think that it's going to be difficult for them to progress and move forward.

PRH is a book distributor. They're an excellent book distributor. They're learning the periodical comics business, but they're really only interested in the largest companies. They may cream the largest publisher clients, but they're never going to support the industry in the sense of distributing smaller publishers and making it possible for new, innovative, creative material to reach the market.

Lunar was a retail/mail‑order company. It was very good at logistics at that scale, but they do not have any of the logistics infrastructure that larger distributors have in terms of running their own trucks, automated warehousing, all of those kinds of things that require substantial capital investment and learnings.

Diamond is, my guess is, maybe half the size it was in 2019. That's a hard place to be, and I've been there. Even if they were profitable, they have had to cut a lot of expenses, and the fact that they've had this drip, drip, drip of more suppliers leaving means that they're never in a position where they can look around, and say, "What do we do next?" They're always reacting to that loss of business. They're in a tough spot. I think it's a strong company financially and well run at the financial level, but that makes it hard for them to change, because they don't have time or money or attention to invest in change at the same time.

I've done that. It's really hard. You can do it, but it takes a strategic vision at the top, which I don't necessarily see existing in great quantity at Diamond or PRH. Lunar is trying, but they're small trying to get big. Everybody's got their challenges, and I don't see any of these companies as a clear winner.

I think the industry is going to flounder around for a while, trying to figure out what to do next as these companies figure out how they're going to adapt to this new marketplace.

Then, the last thing is this Direct Market. 1973, it starts, at least, in terms of the mainstream Code comics. What do you think the legacy is? What did the Direct Market give us that was important?

It gave us geek culture. None of this stuff with the movies, the television shows, the merch, none of that would exist without the Direct Market. Even anime and manga, which has become such a huge force in American culture.

Capital City was selling manga from the very earliest days, and anime DVDs, and before that, VHS. None of these cultural elements, the comic‑based movies, anime, and manga, none of that would have happened without comic stores, which is where these communities of fans that appreciated that form of culture formed.

They could not have been nurtured without these stores where they gathered, were able to see what the new product was, hear from an expert (the person behind the counter) or their fellow fans, and interact with them.

We would be in a very different place culturally in America and the world if the comic stores had never come to fruition through the Direct Market.

Marvel Self-Distributes, Sparking Massive Change

Posted by Dan Gearino on November 15, 2023 @ 5:28 am CT

MORE COMICS

New 'Die' Story Out in November, Alongside 'Die Quickstart RPG Guide'

August 11, 2025

The Die: Loaded #1 will be released in November 2025, the same month as The Die RPG Quickstart Game Guide.

'Hama Files Editions' Will Include a Letter from the Creator

August 11, 2025

Each issue of the Hama Files Editions will include a letter from Hama with background information about the comic.

MORE NEWS

New Tank Battle Board Game by Smirk & Dagger

August 11, 2025

Smirk & Dagger will release Boom Patrol, a new tank battle board game, into retail.

New Weird Swashbuckling RPG

August 11, 2025

Magpie Games will release Rapscallion, a new weird swashbuckling RPG, into retail.