To watch a video of this interview, see "ICv2 Video Interview – Mike Richardson, Part 1."

This interview and article are part of ICv2's Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

Milton Griepp: I'm here with Mike Richardson. Mike is the CEO of Dark Horse, currently a division of Embracer Group. He founded Dark Horse Comics in 1986 (the comic publisher, later a big entertainment company), and also founded a comic chain. He has been a key figure in the growth and development of the Direct Market. We're happy to be talking to him today.

I want to start out at the beginning of your career in comics. When did you become aware of the Direct Market as a source for comics? Was that when you were opening up your first store?

Mike Richardson: In the very beginning, I bought comics from Charles Abar. Remember him?

Sure.

I bought books and product from Bud Plant, and then I applied at different distributors. When I got into the business, I think there were 19 or 20 comic book distributors, including places like Hawaii, New Zealand, and Australia, distributors everywhere.

What year was that?

That would have been 1979.

Was that when you opened your first store, in '79?

Yeah, I started working on it. I actually worked building houses down in Bend, Oregon. I was playing basketball at the time, and I was a commercial artist, and so I worked for a company doing their convention material instruction sheets, designing box covers, and designing new product.

My wife got pregnant, funny thing happened, and sent me balloons attached to a teddy bear and said, "You're a dad." I walked in and did what any new father would do. I walked in and quit my job and moved to central Oregon from Portland because I had always planned to start my own business.

Originally, my plan was to write and illustrate children's books in the back of the store, so I had my art table there and all my equipment there. I had to make a living during that time, and so with a friend of mine who had started a construction company down there, we built two houses. I worked with him pounding nails as we also worked on converting the interior of this building into a store.

What was that first store like? Were you doing new comics and back issues, or what were you selling?

We did new comics (it was a key element), back issues, we did Dungeons & Dragons. I used to call Gary Gygax at his house and say, "I need some more Dungeons & Dragons," and he'd say, "I'll mimeograph some tonight for you and get them out to you." We were with him way back at the beginning, before it became as big a deal, although it was taking off. I was selling a lot of them right off the bat, especially the dice. The dice sold like crazy. People were buying those fast, which encouraged me to keep that game stocked in at the time, because people were buying the dice. We had a whole wall of dice at that store.

Also, there was a company called F & SF in New York that had every science fiction paperback in print. I had a complete stock of all the great science fiction books, the new ones, as well as the old ones, the classics. That was the original store.

I learned my first retail lesson. I was an art major; I learned retail by doing retail. My first big mistake was, I had this great idea in the back issues, I was going to take things like X‑Men #94, which at the time was super‑hot comic. I priced that at 25 bucks, which I think at the time was probably going for $200. I took all these hot books, and I salted the boxes with those thinking that would get people to go through and look through the boxes to see what was there. That was my genius plan.

My very first customer came in in a suit and a tie, looked like he had some money, pulled up in a sports car, went through the boxes and took every one of those books out. My very first customer took them all out. I took a big loss on those and my plan didn't work so well. That was my first retail lesson.

That first store must have been successful because you opened the second one in not too long, right?

Yeah. I talk about the retail, every day was better than the last day. My first day, on January 1st, 1980, I'm trying to remember, we did $8.60, something like that. My wife told my mom (we had a brand new baby, as I told you, and we had just moved down there the summer before), and my wife's mom called her and tried to get her to move back home when she heard that.

She thought the whole idea of a comic shop was pretty crazy anyway, because I had quit a really good job. I didn't quit my commercial art business. I had my own business on the side that I had started while I was in college, so I was doing jobs on the side in Portland while I was working for this other company.

When I moved down to Bend, I didn't have time to do it, so I'd find out-of-work artists or artists looking for work. I'd give them jobs and split the profit with them. My original idea for Dark Horse was going to be Dark Horse Graphics. That was going to be the name of the company. I was going to build a graphic art company down in Bend.

When I talked to so many of the creators who didn't own their own work, when I did the signings in the store, I decided that, as an artist (I considered myself an artist, having had made my living at that up until I started the store, and being an art major in school), it made me angry that I talked to these people and they didn't own their work that they created.

Then I started reading about Siegel and Shuster, who never made any money and were banned from the offices of DC Comics after creating Superman, or even guys like Adams, and recent people who created these things. I know that Barry Windsor‑Smith, when he signed the back of his work, he gave up all rights to anything that he created. It just irritated me, and it put the idea in my head.

I started thinking during those early years of the 80s that I would like to start a publishing company where the creators kept ownership and went into a partnership with the publisher, rather than the publisher taking advantage of their financial needs. We still go by that.

What was your first comic published?

Dark Horse Presents #1.

The anthology, right?

The anthology, which is in my head to start up again. We've done well with it. I edited it for a number of years, the last incarnation, and it's a lot of work doing all those stories in one book. It underlines what a fantastic company Bill Gaines had with EC, because you think about it, they had what, four eight‑page stories every issue? All of their titles were anthologies. To have that kind of talent and keep that level of quality over and over and over with so many eight‑page stories.

Four great stories, not just four stories, four fantastic stories.

Great stories, yeah. The quality level is so high that it's just amazing. I like to pick up one of the old Cochran reprints. We've done them, we've reprinted all those. In fact, we're reprinting the ones that Russ never got to, in order to get everything in the EC library eventually put together. I work with Cathy Gaines and her son Corey. That's the goal, to get everything in print.

You do those hardcovers, and they last, they're around forever. That's why I like to do the archives of certain artists, put them in a hardcover. People forget about them, but once you get them in those hardcovers, those are there forever, basically.

When you started out, how did you sell your comics? Were you selling to all those 19 direct distributors?

We started out, and Richard Finn had a comic book store in Portland called Future Dreams that his partner ended up owning; Richard left and decided to start a comic distribution business called Second Genesis. I made a deal with Richard to distribute the comics, so he did it. He went out and sold to the other distributors. That's how it ended up.

I don’t remember that, but I guess Capital City must have bought from him then.

Yeah, I think at the very beginning, maybe the first year. I think I started talking to you in the first year. Richard was understaffed and had limited capability at that time. He worked hard, but I was looking for a bigger distributor that had the ability to particularly go overseas. That was a big target of mine, is to sell our books everywhere. Then, the second was bookstores; we started from the beginning. You'd read about the aging of the comic book market, so right off the bat, I wanted to get in bookstores, because I always go, "If I want these things, there's got to be other people that want the same thing if they're into comics, or product even." As much as I like collecting (I still collect, I buy stuff on Heritage. When I see a book that I want, I'll spend some crazy amount for a comic)…

I saw you in San Diego with your checklist.

[laughs] That's right. You saw me go through, yeah. I do. I still collect them. I like to collect them, but boy, I like the books. For the person who's not a collector, which is a different market than the reader, it is very different. Collectors are a different breed. I'm one of them, so I know.

I think that people who like to read comics would rather have a book on the shelf than a comic in a box somewhere that they'll never see again or are unlikely to see again. If you have as many comic boxes as I do, you'll understand.

Mike Richardson talks to Paul Levitz (back to camera) at the DC booth, late 80s or early 90s trade show.

Yeah. It's a great deal. First of all, there were the independent distributors, Bay News and all the old newsstand distributors. We would supplement there. We'd go in and buy them. You didn't get that great of a deal. As you know, Phil Seuling started a whole new model, which led to the rise of the direct sales market, which was he cut a deal with the big companies to basically, "Cut my price and we'll buy them non‑returnable."

For me, that was great because we could track our sales of each title. We were religious in tracking the numbers that we sold, even as the stores grew because I wanted that discount. I didn't want to get stuck with inventory either.

You’re talking on the buy side, I'm talking on the sell side. At Dark Horse, you were selling at 60 off...

I'm way back to the retail, OK. [laughs]

You were selling at 60 off, non‑returnable. Did that help compensate creators in the way that you wanted to in the publishing?

Yeah, the first book we did, Dark Horse Presents, I felt like I needed credibility. I gave 100% of the profits to the creators in that book just to get people interested and say, "No, I'm really serious about this."

Profits, you mean beyond printing? Took the printing off the top, and then gave them what was left?

Yeah. That was the great thing. You got your order number in advance, as opposed to the newsstand version.

I read somewhere, I don't know if this is true, that Wonder Woman, for instance, in order to keep the license, they had to keep distributing at one time, and they were selling less than 10,000 of the 100,000 they put out on the stands in order to keep the license going.

That didn't seem like a very practical distribution plan for us. It's why the big companies, which had been around for years, were able to survive. They had recognizable characters. For us, we didn't have recognizable characters.

We had characters that were getting a lot of attention. Black Cross (that first cover by Chris Warner and story by Chris Warner) sold huge numbers. By huge numbers, for us, at the time, it was to sell 25,000, 30,000. That was a big number.

Concrete, Harlan Ellison started pumping it on his radio program down in LA and started pumping Dark Horse as a company. He was taken with us. He actually called me. I knew Harlan's work. I lived in Milwaukie, Oregon (it was farm country), so at the time, I didn't have much experience with so‑called celebrities. I was a little bit tongue‑tied at the first call.

Randy Stradley, who was the first person that I brought onto the company, and I went down to the convention in Oakland. WonderCon was the first one we ever went to. We walked in the door to the hotel where it was at, and there was a long line, so we wanted to see who it was. It was Harlan Ellison signing.

I told Randy (because there were these giveaway sheets from Harlan's new book or something), "I'm going to get in line and see if he knows us." There's no way for him to know us because it had only been a phone conversation. We weren't a well‑known company. I got in line and finally got to him. He was just signing them, "What do you want me to say?" "Say, 'To Bill, from Harlan.'" People just tell him, and he'd write it real quick. It came my turn and I said to Harlan, and to me, this epitomizes Harlan, this one moment. He says, "What do you want me to write?" I said, "You're Harlan Ellison, write something brilliant." He wrote "Harlan Ellison" and handed it to me. [laughs] He did it so quickly. I thought, "That's Harlan."

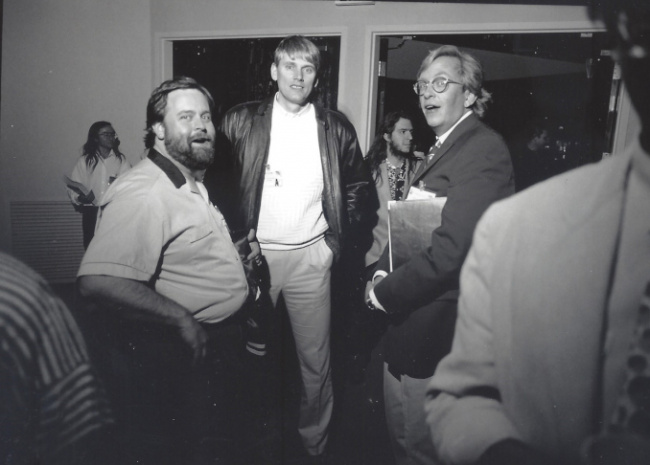

Dark Horse Comics editor Bob Schreck, Mike Richardson, and a surprised Milton Griepp of Capital City, late 80s or early 90s.

I think that we changed the whole way that licensed comics were done. Traditionally, licensed comics were sold by the name of whatever product it was on the book, but the comics themselves, being a collector and having read those growing up, were not terrific.

They generally were not terrific, and they were generally not done with the greatest talent. Basically, get a book out to cash in on a movie or a television series and get it out the door. We didn't think that way at all.

What started me thinking about it was the fact that we were winning awards in the first couple of years with our books, but, like I say, we weren't selling over—I think our big sellers were like 30,000. That was in the days when comics were selling in the millions. I heard one time Marvel canceled books that sold under 100,000.

X‑Men was selling like 300,000 in the mid‑'80s, I think.

Whatever that number was. Anyway, we couldn't break 30,000, and we were one of the successful, what they used to call independents. I don't know what that meant—independent of Marvel and DC is all I could figure what independent comics meant, because it was a hodgepodge of different kinds of ownerships.

I remember going to that same first convention, and there were a lot of companies at that time, the black and white explosion. We met these two guys that did a company called Aircel. I thought, "Aircel, I really love that name. It's like art." I thought of cel work and animation, and I thought, "What a terrific name."

I went up and I talked to them and I said, "I love your name. It's a perfect name, Aircel Comics. I really like that." They said, "Yeah, we named it after the insulation we fill the walls with." [laughter]

Anyway, we couldn't get over the hump with the sales, even though we're winning awards and we're getting a lot of attention. I started thinking, Marvel and DC have these characters that had been around for 40 years or more at the time, and we didn't. We had characters that had been around a year or two. I thought, in the film business, there's all of these characters that are not being exploited in the comic industry. Randy and I sat down and talked about what we wanted to do.

The first one we wanted to do, we had met Hal Saperstein, who ran a company that controlled UPA, I believe it was, who controlled the U.S. rights to Godzilla. Both being Godzilla fans, geeked out on Godzilla, we called Hal and he gave us the license.

We did our first ad campaign right at the beginning. I have it up on my wall. The first week, in the old Buyer's Guide, Maggie Thompson's magazine, we had "Coming Soon," and we just showed a city. Then the next week it said, "Coming Soon in Three Weeks," or something to that effect, and there was a shadow over the city. The third week was "The City in Flames," and fourth, "Godzilla is Finally Here," with a big giant foot on the city.

We sold 60,000 copies, and actually, the printer misprinted the cover. He left the black plate out, so we had this misprinted color. We actually were able to sell some of those as misprints, [laughs] go figure, but we sold out of the regular copies. We got that out. 60,000 was a huge number for us.

Then we started to think, "What movie do we really want to do?" and that was Aliens. [I’m] a huge fan, both the Ridley Scott and the Jim Cameron version, which I think is even better. One's a horror movie, the second one's an adventure movie. If you really look back, Sigourney Weaver and Ripley were the first female kick‑ass action heroes. When Ripley takes over that assault vehicle, pushes him out of the way, and the music going, and she's busting through, and she's going to save Newt no matter what happens, it's a thrilling piece and set the tone for a lot of movies to come afterwards, including Terminator and Linda Hamilton, which is great. She came on to Resident Alien. It was fun to talk to her.

Anyway, the idea was to take these characters that were well known and see if we couldn't do something. The different approach was we didn't just do stories. We actually sat down and plotted the sequel. We wrote the sequel, basically the movie we wanted to see next. At that time, Aliens, the second movie, had come out. We had some ideas. We had Mark Verheiden fly up to Portland and we went over to the restaurant across the street and we sat there and talked about, "OK, it's years later. Newt's grown up. She's having issues and Ripley has to show up to rescue Newt once again. The aliens have gotten loose. The corporation has brought them to the Earth. It's gotten loose and all of this."

Right off the bat, Aliens sold, I don't know, 200,000 copies? That was the first real breakthrough. Then, we just kept reprinting it.

A few years later, when they were doing the fourth Aliens movie, I got hold of the script from Fox and read it and it was the wrong way to go. I went down to Walter Hill. Got a meeting with Walter, and sat, trying to talk him out of doing that version of the movie that became the movie. He was saying, "Well, there's this and that." Finally, he reached under the table, put a stack of our Aliens comics that we had done on his desk, and said, "Look. If anybody had any brains, this is the movie we'd be doing," pointing at our first series. But he said, "It's too late. The die is cast now."

Click here for Part 2.