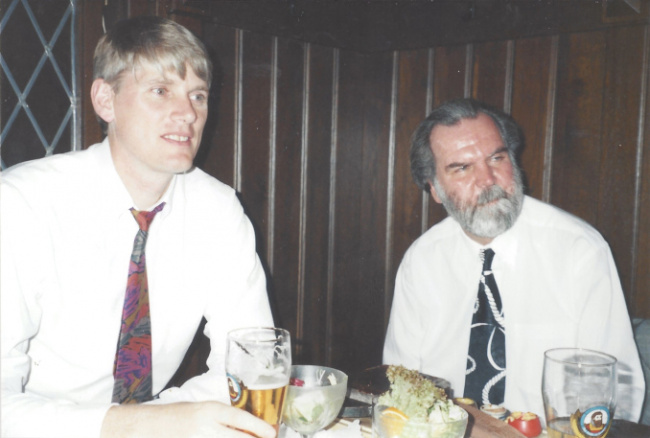

Mike Richardson opened his first comic store in 1980 and not only grew that into the Things from Another World chain but also founded Dark Horse Comics and Dark Horse Entertainment. Dark Horse Comics grew out of Richardson's desire to offer creators ownership of their work, as opposed to the work-for-hire system that was the industry norm up till then. Similarly, Dark Horse Entertainment expanded creator control of media developed from their comics. In Part 2 of this interview, Richardson talks about Dark Horse's first forays into manga and their first feature film, The Mask. In Part 1, he talks about starting his first store and then launching Dark Horse Comics.

To watch a video of this interview, see "ICv2 Video Interview – Mike Richardson, Part 2."

This interview and article are part of ICv2's Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

Milton Griepp: When did you start doing comics in story arcs that could be collected into books?

Mike Richardson: Like I said, almost from the very beginning, I thought that bookstores is where we wanted to be. Right off the bat, I started going to New York for the old, what was it, ABA, American Bookseller Association, meetings. Nobody was interested. I went to every major publisher, and nobody was interested.

I finally did a deal with one of the publishers. Meanwhile, Terry Nantier was able to get our books into bookstores. I couldn't get a deal with anyone. It was interesting because our trades by that time, starting with Aliens, were selling huge numbers.

Huge numbers in the Direct Market, you mean?

The comic books, yeah, and the trades. In the bookstores, I was trying to get those books in because people were telling me in the comic shops that once this book got out and word got out, the comic shops were getting people they never had in their stores to get this Aliens book that we had, written by Mark Verheiden and illustrated by Mark Nelson.

I would go to the ABA and try to show these things, couldn't get any interest at all in them. It was back then when I thought that if the comic readers are aging, the bookstores are the future. We started trying to get our books in there, went with Terry Nantier for quite a long time. Then finally, got into an actual book distributor. They went belly up after a few years owing us a lot of money. We had someone come in and pick up the distribution, a company down in San Francisco. We had a couple of great years and then they went belly up. Went with Diamond for a while. Sales continually got better, but I got to tell you, when we finally went to Random House, we probably put about 200 books back into print over the next year or two, and our sales went way up.

You were also one of the first publishers to do manga in the U.S. Talk a little bit about how you got into manga, and what your experience was in doing that.

As a fan of Japanese comics way back to college, I had seen the Japanese version of Action Comics with Lone Wolf and Cub. I tried hard to get that license. I made the mistake of talking about it to Rick Obadiah, who was a publisher over at First Comics. He went to a party, and there was a guy that had the rights somewhere and I had talked about it. I don't think he had even seen it at the time, so he picked it up.

The problem was, Rick was a friend, but they tried to turn them into comic books. They tried to chop them up, and that wasn't the way.

I finally was able to meet the creator, Kazuo Koike, and we became good friends. I would go over there and golf with him. He actually published the Golf Digest in Japan. He was a big Japanese fan of golfing. In his shop, he had a club designer and maker. I asked him once, "Do you see this?" Because he told me once a samurai sword can have certain choreographed swings, and the golf swing is one of them. I said, "Really? I would have never thought of that." Then I asked him, I said, "Wait a minute. When you have someone making golf clubs, one at a time, and you'd sell them after you use them once, is there a connection between that and the sword makers in feudal Japan?" He just slipped away, didn't answer. [laughter]

You said you were a fan of Japanese comics. Where were you seeing them?

I saw them in different places. I bought a collection of somebody that used to work for me or was given it, I don't remember, when I first had the Pegasus stores. Things from Another World was originally called Pegasus Fantasy Books. I got rid of the Pegasus Fantasy Books because "fantasy" means one thing to me, I found, and something different to somebody else. People would call and say, "Do you have copies of Debbie Does Dallas?" So I got rid of the "fantasy." A surprising number of people equate fantasy with something other than what you and I would call fantasy, and that's where Things from Another World came from, TFAW.

Anyway, because of the art, I had collected Japanese children's books that you can find in different stores. There's a bookstore called Looking Glass Books in Portland that brought in comics from all over the world. That's where, for instance (I'll say this wrong, I understand, but it's the easiest way to say it. If you were an American and it was an American book, it's how you would pronounce it): Metal Hurlant. I'm not going to try and say it in French.

[in French] Métal Hurlant.

[laughs] See, I'm not even trying. I have the whole run. I bought them as they came out because he would go on buying sprees. It's where I learned about the underground comics while I was in college and I used to spend a lot of my disposable income, which wasn't a lot, on books from around the world at his store. Probably some of them there.

What really drove me was when I saw Lone Wolf and Cub and I thought, "Wow, I really like this, and I've got to find out." The interesting thing was when I first started going to Japan, which was in the late 80s, I'd go to a bookstore. How I’d choose books that we're going to publish, I'd stand in the bookstore, and I’d go down the rows, and I'd be there for hours. It became known in Japan that this tall guy would come to the bookstores and stand there looking at them for hours. That's where I picked the books. That's how I picked them because the really good books you could get a sense of the story, and of course, for an American audience, all the Japanese art styles aren't saleable over here, at least back then.

I looked for a certain type of art that I thought would be more attractive. Then I met Toren Smith, who had a company called Studio Proteus, who used to go over there all the time. I'd give him targets, and he'd go get the license for me. Eventually, I met all the publishers over there and was well known over in Japan, which I think I still am, maybe.

Another way that Dark Horse expanded more successfully than any other comic publisher that wasn't one of the big two is into entertainment. How did you get into the entertainment side of the business, and why were you more successful at it? What did you do differently?

I could read when I went into the first grade. I was already reading because my mom would bring home comics. She was young, she had me when she was 18, and she was a comics fan growing up, so she always brought comics home. I wanted to know what was inside, so I insisted, very young, that I had to learn how to read. She'd bring me reading books and help me.

I was asked one time in an interview about school, and I said, "I was generally bored in school." I was asked, "When did the boredom start?" I said, "I could read when I went into the first day of school. They passed around Fun with Dick and Jane and I read it while it was being passed around, so probably, my boredom started the first day, the first hour of the first grade."

I read comics all along, so I always, in the back of my head, "Wouldn't it be great to be able to do your own comics?" Then, of course, I was a huge movie fan also.

When we started Dark Horse, again, as I told you, I felt the comics creators were not being treated fairly by the publishers. I have some horror stories that were told to me as the years went by of how really brilliant creators were treated and lost rights and all that.

In the film business, I started getting calls from studios right off the bat, people wanting to license our books, but just as in the comics business, what was common back then is a comic creator would get contacted by a producer and they would say, "Oh, this will be great. We'll do all of this, blah, blah, blah," and then they'd sign the contract and never hear from them again, never have anything to do it. I know, for instance, Dave Stevens had a really poor deal for him and I had met Dave. He actually went to the same high school as my wife.

The Rocketeer you're talking about, right?

Yeah, for The Rocketeer. He had to get permission whenever he wanted to do anything from the studio.

First of all, I was a movie fan, but the real reason was, I said "OK, I have to produce," because I thought that's the only way we could protect the property, if I was a producer. I got told how stupid I am. I got cussed out on a Friday three times by one of the studio's agents or executives trying to get a property from me, and I said, "No, only if I can produce."

Once I got an agent and actually did produce, I could put things in the contract that weren't there before. For instance, we negotiated holdbacks. Except for a window around the movie, if you did one of the comics of one of our creators, you could not stop them from doing what they had done before that movie got made. In other words, they could still do their comics, they could still sell their merchandise, they could still do all that. So we divided it. Maybe somebody else did that; I'm not aware of it. What I did was have classic merchandise. That was a category that we devised with my attorney, people like Keith Fleer and Irwin Russell. We worked that out so that we had a whole category that was exempt from whatever movie rights that they took.

Basically, it was fair to the studios because they got to do the product based on the film version. The creator got a piece of that, and the studio got a piece of the increased sales that a movie would bring, not the basic sales we had always had, but the increased sales. That seemed fair. What we did is negotiate a fair deal.

The key person in that whole thing: as I'd been turning down deals, a legendary producer by the name of Larry Gordon called me and basically said, "Hey, boy. You want to do movies? Get on down here and we'll do movies." Went down, met Larry, still work with Larry to this day. We have projects right now. He's been telling me for 20 years he's retiring, but we keep doing projects off and on together. Larry short-cutted me. He introduced me immediately to the heads of the studios and the key people.

"You better learn what a producer does," he said, so he put me on as a producer of a low‑budget horror movie called Dr. Giggles.

I remember.

…which starred one of the actors in L.A. Law, the mentally challenged character. Anyway, it did well. It did pretty well, and so got a little bit of attention. Then Mike DeLuca at New Line—actually, The Mask was seen by their licensing guy, a guy named Kevin Benson that was head of licensing at New Line Cinema. He always bragged that he was such a good licensor for New Line that he actually got a Freddy doll in children's toy stores, which created an outrage among parents, but I thought, "Wow, you can sell that to children’s toy dealers, then you've got to have a good gift of gab, I guess."

Anyway, he got the property in front of Mike DeLuca. Lisa Henson at Warner Brothers was trying it, and Lisa was great, but DeLuca said they've got 100 projects. I was new in the business. They said the fact that they have yours doesn't give you any guarantee that that movie will ever be made. He said most of them never are made. He said, "I'll make your movie. You bring it to New Line and we'll make it." We did and went through, I don't know, it took us five years to get it off the ground from that time. They wanted me to approve Rick Moranis at one time. Terrific actor. He's not The Mask. Then, it was Martin Short. Terrific actor, not The Mask. Then, DeLuca called me one day and said, "Have you ever heard of Jim Carrey?" I said, "I don't think so." He said, "You know the white guy on In Living Color?" I said, "Fire Marshall Bill?" He said, "Yeah." I said, "You really think that's the guy?" He said, "I'm going to send you a tape." He sent me up a tape of Jim doing My Left Foot for In Living Color. I was laughing. It was hilarious. I called him and said, "That's The Mask."

Meanwhile, from Dr. Giggles, one of Larry Gordon's people (I wish I could remember her name) started calling me when she heard we were going to do The Mask. She said, "You've got to see this girl. Her name's Cameron Diaz. You've got to see her." I said, "What has she done?" "She hasn't done anything. She just graduated from high school." I said, "I don't know," but it went on and on. Finally, I set up a meeting for her to go and get an interview there. I'm a little fuzzy now, but I think she started out looking for a bit part and ended up getting the lead. I know Chuck [Russell] was a big fan of hers from the moment that he met with her. When you saw the dailies, when she did her test in the dailies, she was fantastic. She was great.

It's just like magic because there was so much charisma between Jim and Cameron. I'd love to show what was after each one of those scenes they were together because a good portion of the time Cameron would break out laughing because she's trying to hold back this laugh. I think it gave a sparkle, also, to her performance there just because Jim was so funny. Every time he did a scene over, it was different. The Mask took off in sales.

Then, another project that I had come up with that I worked on with Mark Verheiden. That was Timecop. That knocked The Mask out of first place, so I had the number one and two movies. There were articles in all the magazines, then I was in the film business.

By the way, I worked on that script [The Mask] too but I got no credit for it because I wasn't a member of the WGA, but then, on another project [Timecop] that I worked with Mark, Mark supported me when I said, "Wait a minute. This was my story that I worked on with Mark." He supported me, so I got a story credit on it.

I want to point out, we still stick to the same thing. If the creatives want to be involved, they can be as involved as they want. With The Umbrella Academy, which is our big hit at Netflix, Gerard [Way], he's there working with him as much as he wants. The same thing with our artists. They're there working on the project.

I want to wrap up with a few questions about the present and future. On the present, Dark Horse has been part of the recent changes in distribution in the Direct Market. What do you think of the current structure of the Direct Market and where do you think it's going?

Unfortunately, there's some other people getting into distribution but the resources that a company like Random House has makes it difficult to say no to them. Their reach, their financial success, their sales force, which is incredible, those are things that the direct sales market distributors never really had.

It was very hard for me to leave [Diamond]. It was the same as it was hard to leave your company, Capital, at the time. Those are hard decisions to make when you know the people that run those companies and you know the effect they have.

With Diamond, Steve's a friend of mine. It was hard to tell him, but as was told many times to me, it's just business, and sometimes you have to take that attitude because you have to make the best deal for your company to keep your company strong.

The direct sales market, as you know, brick‑and‑mortar stores had a tough time over the COVID period. A lot of good ones disappeared. I think it's still viable. I think people still want to buy comics. We have our stores, not as many as they used to, but they are clubhouses. People come down and they can talk about comics. They can look over what's there. They can order in advance. I think it's all good. But quite honestly, it's the trades in the bookstores right now where most of our sales occur.

What about the comic periodical? You moved heavily into the book business. Do you think the comic periodical has a future?

I think it will always have a future. The problem is it keeps getting more and more expensive. How long will consumers back a product that is now sometimes costing five dollars for 22 pages of story, and then you wait a month for the next issue? It's a hard model. It's a relic of the 30s where it was state of the art.

You don't have those printing presses anymore. You don't even have that kind of paper anymore. People wouldn't accept that kind of paper now, the old pulp. Comic books were basically, as they started out, just a sheet of newsprint folded a certain number of times, you put magazine slick on the outside, and you put two staples in it. It was a very cheap item for them to produce.

Now we're emulating that, and it's not really financially viable. We'll do it. We'll sell as many as we can, but comics don't sell millions anymore. They very rarely sell hundreds of thousands anymore. There's competition now. Of course, everyone knows this. When I was a kid, we bought MAD Magazine and comics and then went to a movie for a quarter. That was our entertainment, and maybe every so often a yo‑yo came along, or a Frisbee, or a Hula Hoop, but there weren't that many choices. Now video games are the big things. My grandkids, for instance, they're interested in manga. Not so much comics, but manga, because of the anime that they see on television. That's a good help.

The movement in the early 2000s of shojo for teenage girls, I didn't believe it because, as you know, coming out of the direct sales market, very few girls came to those stores. I had 12 stores at the time in three states. I went out to a Borders and walked to the manga section, and here's a dozen girls sitting on the floor reading comics. That changed my mind really quickly.

We actually ended up getting into a deal with CLAMP, which was the Beatles of manga over in Japan at the time. I started flying over regularly a couple of times a year. Same thing with Dark Horse in the U.S., I became friends or acquaintances with the key talent. I met all of the talent of the books that we did, or as many as I could, and got to know them, and was actually warned at times, "Please leave our creators alone." They're very protective of their creative relationships, which I try to respect.

You started Dark Horse, I think, in '86. It's been 37 years. What do you consider your biggest publishing accomplishments in that time?

I think we were one of the companies that opened up creator rights. When we got Frank Miller to turn down Marvel and DC and come with Dark Horse and see huge numbers, I think that changed the game for comics creators.

When was that? When did you do your deal with Frank?

I think we did the deal in '91 and the first books came out in '93.

So, pre‑Image.

That was one of the influences on Image, when Frank went. In fact, I was in discussion with those guys after Frank went, in discussion with Todd and Jim. The big thing that I refused to do was they wanted 90% of the profits.

I said, "We can't. There's so much that we don't charge to the book. We can't do 90%. If you go somewhere else and they offer 90%, you're not going to get it." That turned out to be true. It's not a business model that you can sustain. There's so many things that don't get charged to a book. You've got to make a profit on top of that.

Creator rights, that was a big thing. Anything else?

I think creator rights, I think the royalty reporting. (Although, we have several thousand people, so we have a limit. If they ask, anybody can have their royalty report, but it's only the books that sell over a certain number that we give quarterly. Back then, everybody got something quarterly, which was very different at the time.)

When we met with Frank down in Los Angeles, I had every possible version and every possible cost at every sales level done on sheets so when I met him I said, "Here, tell me what we can make." He called Dave Gibbons and he said, "Hey, I just met this guy who gave us the keys to the kingdom," because they had never seen it. They didn't know what a book cost. They didn't know how much it cost to print it. They didn't know what it cost to ship it. I gave them everything. He came back the next day, called me, and said, "Meet me at the same place." I had flown down to LA with Randy and I shook hands with him right there. We pretty much have dealt on a handshake ever since. We sign them, Frank rarely signs something, so we just go on the handshake. He always said that's good enough for him.

Frank coming to Dark Horse was a huge moment for us because then creators took us really seriously. We were getting the ones coming up or the ones that were good in that second tier, and even ones that were award‑winning and well‑known, but when Frank came, we got the big sellers. The big, high‑profile creators took notice and it changed everything.

And film, changing how comics creators were treated in the film business. I know we got language that hadn't been put in the contracts before. I know because we fought with the studios over them after I got those in there. To this day, we have to fight to get our precedents. But we do. We do the best we can every time, based on our precedents.

What else? The quality, our pushing the bookstores, all of those things, I think, at least helped the market. It helped creators, which was always my goal.

Thanks very much. I appreciate your time and sharing all those great stories.

I've got a lot of them, [laughs] as you can tell.

Bringing Manga to the U.S. and Bringing Comics to Hollywood

Posted by Milton Griepp on November 17, 2023 @ 4:32 am CT

MORE COMICS

Showbiz Round-Up

July 28, 2025

San Diego Comic-Con is in the books, and lots of Hollywood news has hit the wire. Time for a round-up!

Also: Longtime Eisner Awards Administrator Jackie Estrada to Retire

July 26, 2025

Jackie Estrada, who has been running the awards since 1990, is stepping down.

MORE NEWS

'The Millerax'

July 28, 2025

Arcane Tinmen will release The Millerax , a new line of Dragon Shield accessories, into retail.

Heads to Gamefound Soon

July 28, 2025

Renegade Game Studios announced Ikusa: Samurai Swords - 40th Anniversary Edition , a new edition of the Avalon Hill strategy game.