These two recognized exceptions to the exclusive rights the law grants to copyright holders recognize the importance of historical reference, imitation, satire and recontextualization of work to creativity and innovation. However, they are ambiguous and prone to abuse—sometimes to prove a point, and sometimes just to make a buck. The odd part of this is that the ambiguity is built into the structure of copyright law itself - to deal with the wide variety of ways people use existing art work.

This is a pretty dense way to start off a column on comics, but a couple of things brought these issues to mind recently.

For arts’ sake. The first (non-comics) example is the story of artist Richard Prince, who recently sold photos that he grabbed off Instagram, including some of Suicide Girls, for prices as high as $100,000. His legal rationale is that Instagram photos are explicitly not covered under copyright according to the site’s terms of use, that he has distinctively transformed the photos by adding some lines of text underneath them (and so they are an allowed fair use and derivative works under copyright law in any case), and more broadly, that the entire project including the shocking commercial element are actually part of the art. That is, the disgust any reasonable person experiences when hearing this story is the intended effect of the creative project.

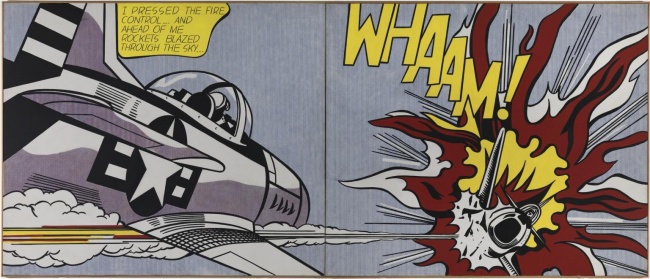

Fine artists going back to Marcel Duchamp and noted comics plunderer Roy Lichtenstein have already been down this road. Reasonable people can argue about the aesthetics, but it’s undeniable that making small alterations to an existing work then asserting that work is now worth hundreds of times more than the original because of its “transformation” at the hands of an artist does get attention.

This brings us to the second example, one more relevant to comics.

Conventional ethics. Last weekend I was at Denver Comic-Con, an independently-run show that has quickly grown into one of the largest in the country. Though it showed some clear signs of growing pains, particularly in the shambolic programming process that resulted in the regrettable (though not characteristic) “no women on the women in comics panel” headline, DCC appears to have provided a great experience for its nearly 100,000 attendees and a big boost to the local economy.

One aspect of this show that’s become common at big regional cons is the absence of the largest comics publishers. Marvel, DC, Image, IDW and Dark Horse simply can’t make it to every convention, even ones that crack the top 5 in attendance in North America. The same is true of big-name creative talent. There’s only so much to go around, and popular creators need to actually create sometimes, rather than sit behind a booth at conventions.

That leaves the exhibit hall to be dominated by small retailers and independent artists. DCC made a special effort to showcase talent local to Denver and Colorado, with large swaths of “Artists’ Valley” dominated by lesser-known creators.

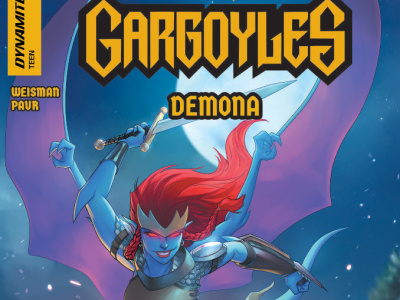

How are these folks making money? Some are selling their own books and merchandise, but a huge number are trafficking in prints and original artwork of characters they did not create and have never worked on professionally.

Fan art as business model. A lot of this merchandise is essentially fan art – which might be fine as portfolio pieces or displayed free on social networks, but becomes a legally dubious proposition when offered for sale in a public venue like a comic convention. These works may be “transformative” of the underlying property from a copyright sense, but some of these characters and their distinctive logos are also trademarked – and that’s a different story.

Fan art is a nightmare for IP owners who have to protect their copyrights but don’t want to come off as jerks for suing their most enthusiastic fans – or artists who may not have money to recover in any case. But what about when fan artists are competing for the same dollars as professional creators who materially contributed to the popularity of the property and may have permission from the companies to create and sell their work?

Is this worth paying attention to? Perhaps. According to the preliminary data from a new survey I’ve been conducting on convention attendance for Eventbrite, artwork accounts for a large percentage of spending by just about every category of attendee. And it clearly represents a major area of focus for convention organizers trying to fill space in cavernous exhibit halls in the absence of big publisher anchor booths.

Not such a gray area. Commercialized fan art is a potential legal, ethical and PR morass, but there are still some cases of not-so-fair use that are a little easier to adjudicate.

A few days ago, cartoonist Scott Shaw! mentioned on his Facebook feed that he’d noticed someone on Amazon selling bumper sticker decals of an image taken directly from the cover of Captain Carrot and the Zoo Crew #1, which he had drawn. The same seller specializes in decals and wall clings featuring various pop culture images including sports team logos, corporate insignias and cartoon icons like Peanuts.

“I seriously doubt this is officially licensed product,” quipped Shaw. “Hey DC! Sic some of those savage Warner Brothers lawyers on these criminals ASAP and get me my fair cut of their unfair profits!”

In our visual age, established artists, wannabes and scammers all want to help themselves to striking comic and pop culture iconography that gets attention and provides instant buzz – even when the images have been created by others. Digital technology has made the appropriation and distribution of imagery so ridiculously easy that even the power of savage attorneys is insufficient to keep the urge to plunder in check.

--Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.