Rolling for Initiative is a weekly column by Scott Thorne, PhD, owner of Castle Perilous Games & Books in Carbondale, Illinois and instructor in marketing at Southeast Missouri State University. This week, Thorne briefly comments on background checks for game judges, then looks at the role of designers in selling games.

I had kinda planned to comment on Wizards of the Coast's announcement requiring WPN stores to conduct background checks on staff or others who "interact with the public on your behalf" but since I have not seen any official communication from WoTC, like a letter or email, I will wait. Incidentally, since a lot of their customers are younger, The Pokemon Company already conducts background checks on their tournament organizers and judges. Since The Pokemon Company conducts the checks itself and absorbs the costs, one of the reasons, I hypothesize, it takes a while to get certified as a Pokemon TO or judge, the company has access to the checks and can make a decision on its own as to whether to sanction a Tournament Organizer or not. So, if you play in a sanctioned Pokemon, you can rest assured that the official reps have been checked out.

Instead, I wanted to comment on an aspect of this blog post to which Will Sobel of Upper Deck Entertainment called my attention on "The Ethics of Buying Board Games (Part 1)." I don’t want to focus on the ethics part of the post, since it doesn’t look as if the author will really dig into that until part 2. Instead, I want to look at the section of the post titled "Starting at the Start" and the point Connor Alexander makes regarding how most customers, with rare exceptions) have no idea who designed a board or card game, certainly nowise as much as they do in the comic or book fields.

Take novels. It is all about the author. There is a reason why Stephen King has had over 100 books published. People know his name and what to expect when a new Steven King book releases. There was a reason why people lined up for blocks waiting for the new Harry Potter book to come out. They knew the author and they knew what to expect. I still keep an eye out for John Dickson Carr novels. He died back in 1977 but I like his writing and know what to expect from one of his books, so will always read one when I come across a title I haven’t read.

Similarly in comics, for decades it was the character that mattered, that and in some cases the publisher, hence the reference to the "Marvel Zombie" of the 1970s through the 1990s, a reference to avid Marvel fans who purchased every Marvel comic that the company published. In more recent years, fans have become more discerning, purchasing series from writers such as Robert Kirkman and Neil Gaiman or artists such as Bill Sienkiewicz. Witness the attention that Brian Michael Bendis’ recently announced move from Marvel to DC generated.

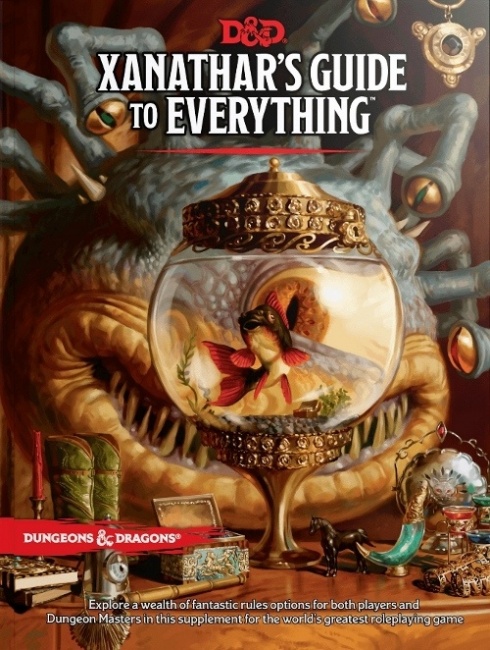

With very few exceptions (Monte Cook and Reinier Knizia come to mind), the game industry does not see this type of name recognition or following of authors or designers. Case in point, the recent New York Times best-selling Xanathar’s Guide to Everything. Without looking, almost everyone knows it is a book for the Dungeons & Dragons system but almost no one knows who wrote it. Customers buy based on brand name. If I am a fan of Dominion or Munchkin or Savage Worlds, and an expansion comes out, I will probably buy it despite not knowing any more about it than that. Conversely, if the designer of Savage Worlds or Munchkin or Dominion comes out with a new game, the average customer won’t know about it, since the average customer doesn’t follow designers, they follow brands. Greg Costikyan pointed this out back in the 1980s, arguing for giving writers and designers more prominence on games. It was a concern then and still a concern today.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Column by Scott Thorne

Posted by Scott Thorne on January 22, 2018 @ 12:25 am CT

MORE GAMES

Releasing this Month

August 14, 2025

Steve Jackson has announced the Munchkin: Not My Monkeys expansion, releasing this month.

For 'Cosmere Roleplaying Game'

August 13, 2025

Brotherwise Games will be launching the Cosmere Roleplaying Game: Stormlight series.

MORE COLUMNS

Column by Scott Thorne

August 11, 2025

This week, columnist Scott Thorne notes a new twist in the Diamond Comic Distributors saga and shares his thoughts on the Gen Con releases that will make the biggest impacts.

Column by Jeffrey Dohm-Sanchez

August 7, 2025

ICv2 Managing Editor Jeffrey Dohm-Sanchez lays out the hotness of Gen Con 2025.