Confessions of a Comic Book Guy is a weekly column by Steve Bennett of Super-Fly Comics and Games in Yellow Springs, Ohio. This week, Bennett looks at a recent opinion piece that argues that superhero entertainment should be getting the same kind of current re-evaluation as TV cop shows.

You might have heard about the new HBO Max Batman TV spinoff from Matt Reeves and Terence Winter (here via Indiewire), set in the same universe as the forthcoming feature film starring Robert Pattinson. It’s currently untitled, although some have noted the similarities to Gotham Central, the police procedural comic from writers Ed Brubaker and Greg Rucka. But given the protests going on all over America these last few months, now might not be the best time to launch a new cop show.

There have been increasing calls for a re-examination of fictional cops that's led to such previously unthinkable things as the cancellation of Cops, according to the New York Times, and a second look at even supposedly benign kid shows like Paw Patrol, the very popular Canadian CGI–animated children's television series about a unit of adorable animal first responders that includes Chase, "a German shepherd who is also a cop." Despite it essentially being "a pretense for placing household pets in a variety of cool trucks," as writer Amanda Hess put it in her piece, "The Protests Come for Paw Patrol," in the New York Times, it’s being criticized for being another show that says cops are "implicitly the good guys," which for a lot of people, like me, is a view that’s hard to view as being controversial. It was the message baked into essentially all American TV shows about the police, one that I uncritically absorbed over decades of watching shows like The FBI, Dragnet, and even The Rockford Files. The police may have given Jim Rockford a hard time, but they were still always presumptively the "good guys."

It shouldn't have been that big a surprise when it turned out that the police weren't perfect and reality was a lot more complicated than T. J. Hooker; it was, after all, fiction, a sanitized, idealized, idolized fantasy about an actual occupation. In the same way there were real-world knights, pirates and cowboys that were almost nothing like their fictional counterparts, TV crime shows are as close to the reality of police and police work as Gunsmoke was to actual life in 1870s Dodge City.

Currently, police procedurals and comedies make up 60% of current network offerings, so it's hard to believe the protests will kill the genre as we know it. But fantasies do fall out of favor when they become too removed from the reality of their audience. In 1960, there were 30 westerns on prime-time network television; today no network would even consider putting one on their Fall schedule. Genres are like Tinker Bell; stop believing in them and they disappear.

Current events do impact entertainment. Recently (see "Confessions Of A Comic Book Guy -- Playing Catch Up") I wrote how the assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy was a contributing factor to the death of the action/adventure cartoon for nearly a decade and the creation of Scooby-Doo. The entertainment industry has to keep up with the latest societal changes and television producers are already trying to figure out the best way to address the public's changing attitudes about the police, for example in changes to the scripts for the upcoming season of Brooklyn Nine-Nine, per USA Today.

With some notable exceptions, America generally doesn't do crime or cop comics, but since superheroes share the same sort of good guy/bad guy paradigm, I kind of knew it was just a matter of time before someone decided to re-examine superheroes the same way. Then I saw the piece by Eliana Dockterman in Time titled "We're Re-examining How We Portray Cops Onscreen. Now It's Time to Talk About Superheroes." While Dockterman acknowledges superheroes can be "beacons of inspiration," she also sees them as "straight, white men who either function as an extension of a broken U.S. justice system or as vigilantes without any checks on their powers," ultimately asking, "What are superheroes except cops with capes who enact justice with their powers?"

While writing about superhero movies like Captain America: Civil War and Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, Dockterman says that "given that the creators and stars of these movies have historically been white men, it’s hardly surprising that so few reckon with issues of systemic racism—let alone sexism, homophobia, transphobia and other forms of bigotry embedded in the justice system."

Dockterman says "it’s increasingly unclear how either the 'arm of the law' or the vigilante narrative can survive without serious reconsideration," but she does have a few suggestions as to how it can change for the better. She would like there to be more BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) creators, as well as writers who can "shake the notion that they are bound by the strictures of outdated intellectual property" and "snatch up those familiar characters and still weave a new story, with new politics and a new perspective, using only fragments of what came before." Like the way Damon Lindelof’s 2019 HBO series version of Watchmen did.

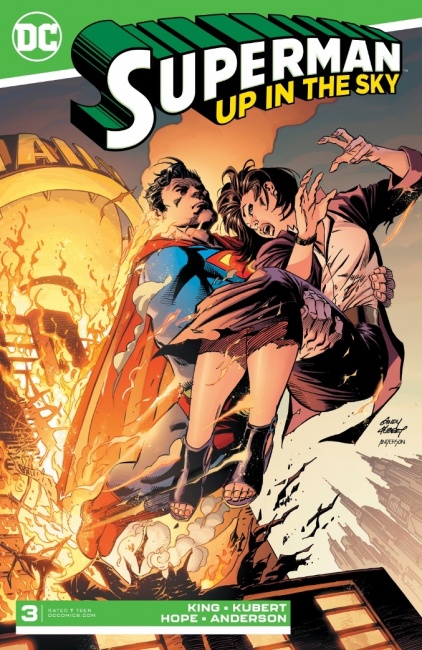

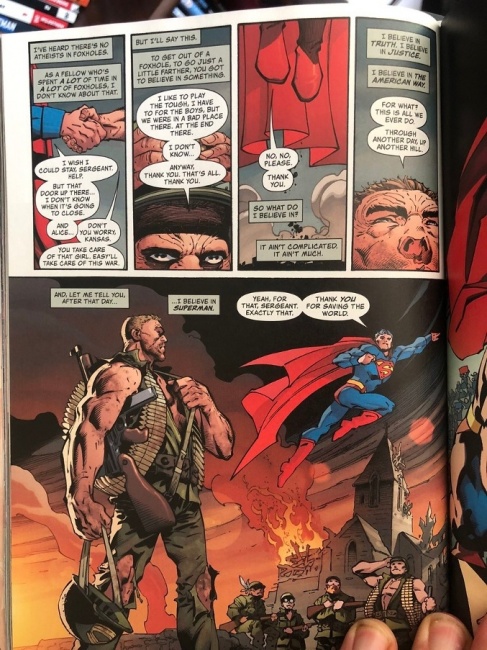

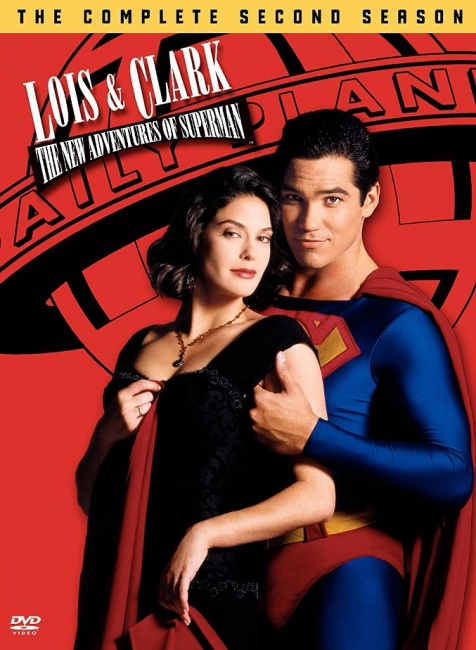

Naturally, there was pushback against this, as reported by Fox News in its article "Time magazine blasted after writer calls for superheroes to be 're-examined' along with police;" and in Fox coverage of the reaction by actor Dean Cain. It was during his interview on Fox & Friends that the former star of Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman claimed, "I promise you that Superman -- I wouldn't today be allowed to say: ‘truth, justice, and the American way.’" When of course writer Tom King had that very thing last year in an issue of Superman: Up in the Sky.

Cain doesn’t comment on any of Dockterman’s ideas which is a shame because they're worth exploring. For starters she acknowledges the obvious; the world is changing and if superheroes don’t want to be permanently left behind they’re going to have to adapt and change to the world that’s coming. It helps that she accepts the idea that "justice for all" does in fact mean everyone and wants to see "more superhero tales that adequately grapple with the complexity of justice in America.”

Cain claims "the author of this article makes a bunch of claims that are totally untrue;" which is true. The Avengers do not, as Dockterman says, "work for the secretive agency S.H.I.E.L.D." and Batman certainly doesn't "take orders from Gotham police commissioner Gordon." She seems to believe superheroes operate exclusively as either semi-sanctioned government operatives or self-appointed vigilantes, unaware there’s a third option. Dockterman asks, "What are superheroes except cops with capes who enact justice with their powers?" Well, I think I have an answer for her.

Back in the Golden Age of Comics there were boatloads of patriotic avengers and dark crime fighters but they also frequently served as what I’ve come to call Officers in the Court of Last Resort. America embraced superheroes because of their colorful costumes and amazing abilities, but also because the public was frustrated with corruption and an often unfair legal system. And these new masked mystery men dealt with the corrupt politicians, manufacturers of adulterated products, criminals who thought themselves above the law and helped those the law had failed. Not because they hated capitalism, law and order and America, but because they wanted a fair and just country.

It worked once, twice if you count the "socially relevant" comics of the 1970s; maybe it’s time publishers tried it again.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Column by Steve Bennett

Posted by Steve Bennett on July 15, 2020 @ 8:27 pm CT

MORE COMICS

From Tiny Onion, Dynamite, Image, IDW

July 18, 2025

There are four Humble Bundle deals running right now, from Tiny Onion, Dynamite, Image, and IDW.

From Marvel Comics

July 18, 2025

Age of Revelation, a new status quo taking place 10 years into the future and arising out of current developments in the X-Men titles, begins in October.

MORE COLUMNS

Column by Rob Salkowitz

July 14, 2025

Superman isn't a character who needs a general introduction to the broader public; he just needs an existing global fanbase to take a fresh look.

Column by Scott Thorne

July 14, 2025

This week, columnist Scott Thorne discusses Green Ronin Publishing's GoFundMe to fund its legal fight against Diamond Comic Distributors, and the soft preorders for the latest Horus Heresy box.