This is the keynote address given by former DC Comics SVP Bob Wayne at the Diamond Retailer Summit, which took place in Dallas, Texas, on June 7-9, 2023. We share it here as a guest column.

We also recently interviewed Wayne to talk about his early days in retailing comics (see "ICv2 Interview – Bob Wayne" or for the video version, see "ICv2 Video Interview – Bob Wayne").

Wayne was one of the early retailers we interviewed for our article on the creation of the Direct Market (see "How the Drive to Get Comics Created the Direct Market").

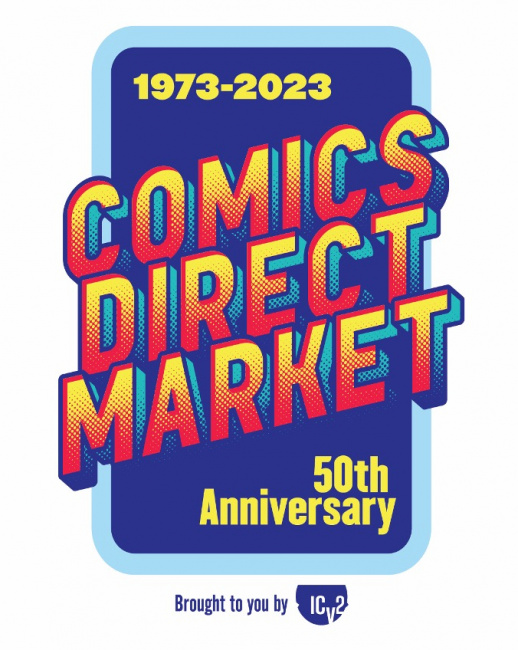

This guest column is being presented as part of ICv2’s Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

That caricature is by the former Art Director of MAD, Sam Viviano. At least I think it’s a caricature. He may have meant it as a portrait.

Thanks to Steve Geppi and the Diamond team for inviting me to deliver the keynote for this year’s Diamond Retailer Seminar. They’ve brought me here at great expense, as I crossed the same river multiple times in the long 35-mile trek to Dallas from stately Wayne Manor in Fort Worth.

So, howdy y’all.

Growing up with the last name Wayne, learning to read primarily from 1958-59 DC and Dell comics, I’m sure at some point I dreamed I’d make a living in comics. But if you had told me in 1958 that I’d be reflecting on a career that allowed me to meet folks like Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Bob Kane, Carl Barks, Will Eisner, Sergio Aragones and Alan Moore, I would have been skeptical. (I also wouldn’t have known who any of those people were.)

Especially with my bad experience in 1960. Let me explain.

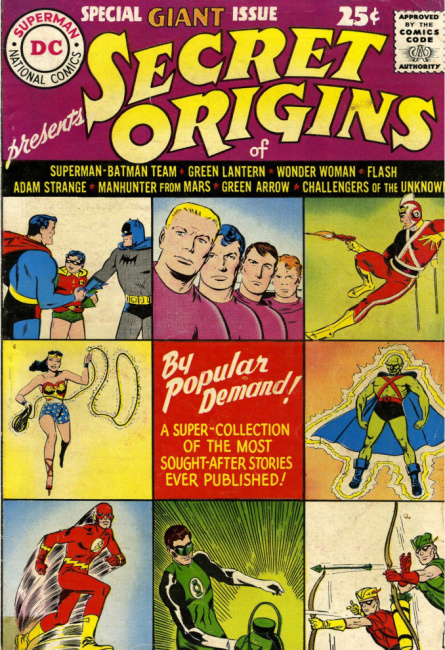

As a kid, I always loved origin stories. In fact, one comic published in 1961 eluded me for 15 years. I finally found a copy at my first New York City convention. That was DC’s Secret Origins #1. I found it and met legendary DC editor Julius Schwartz on the same day. He wasn’t impressed. He already had a copy.

Speaking of origin stories—and we all have them—here’s part of mine.

My paternal grandfather was a bus driver for Trailways in the 1950s. He usually drove a roundtrip from Fort Worth to the beach resorts in Galveston. At the end of each drive, he would walk through the bus and pick up any comics that were left behind by the passengers. He would give me those comics whenever we went to visit him. Not surprisingly, I frequently asked to visit him.

When I was four, I had a year as the stereotypical sickly child and spent much of that time indoors with my mother reading comics to me; that, and watching The Adventures of Superman on our black & white TV set. I grew frustrated that she wasn’t always available to read them to me, so I convinced her to teach me how to read.

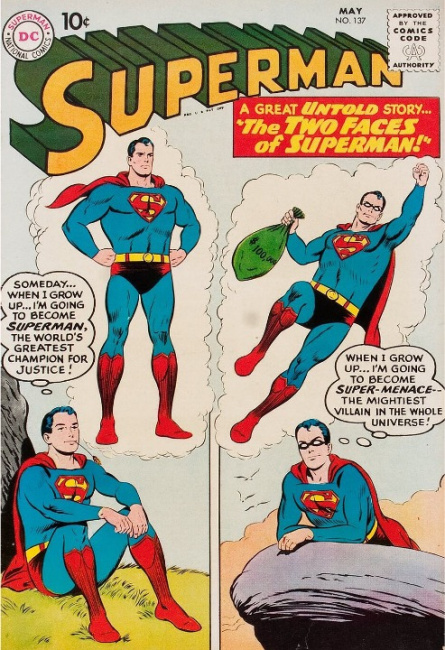

The first comic I remember purchasing with my own money was Superman #137, cover dated May 1960. (On sale March 17, 1960.) When I was five, every 10-cent comic was a significant portion of my allowance!

When I started the first grade in the fall of 1960, I was already reading at a DC Comics level before I walked into the school. They tried to teach me how to read with the most boring stories I had ever seen. Dick, Jane and Spot, their incredibly annoying dog. Our teacher Mrs. Turner read us a bit of this boring "Run Spot run. See Spot run" stuff and then asked if anyone knew why Spot was running.

I raised my hand and replied that it was probably Red Kryptonite.

Without saying a word, she took me by the arm, out of her classroom and to a bench outside of the principal’s office. I sat there while she went inside. She came out of the office and told me to sit there and wait for my mother, which seemed odd because I rode a school bus. I wasn’t really sure my mother could even find the place. But she did. They told her there was something wrong with me. My mother was already quite familiar with the random effects of Red Kryptonite and suggested that they didn’t realize that I already knew how to read and that they weren’t going to take my imagination away from me. "What if he needs it to make a living?"

So I was back in class, and still allowed to read comics.

I started buying duplicates of the comics I was sure would be valuable at some point in the future. For example, I bought two copies of everything I could find by artists like Neal Adams and Jim Steranko.

(There’s nothing that compares to being in a business meeting with Neal Adams and pointing out that you rode your bicycle to buy the comic he’s discussing…)

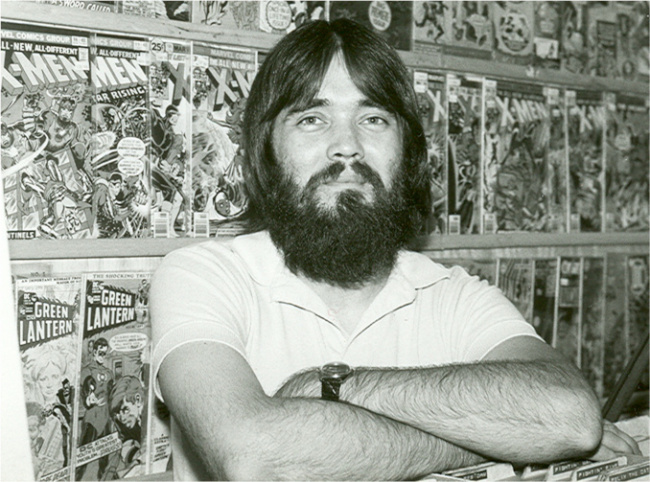

It didn’t take me too long to start selling new comics to my friends and at conventions in 1973 as Seagate account #40. I was 19. (And yes, most days it absolutely feels like it’s been 50 years since 1973.) Milton Griepp and his ICv2 team are organizing a celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the Direct Market this year, and I think this is a great time for us to reflect on our shared history.

Retailer-distributor-publisher relations were different in those days. Let me give you two examples.

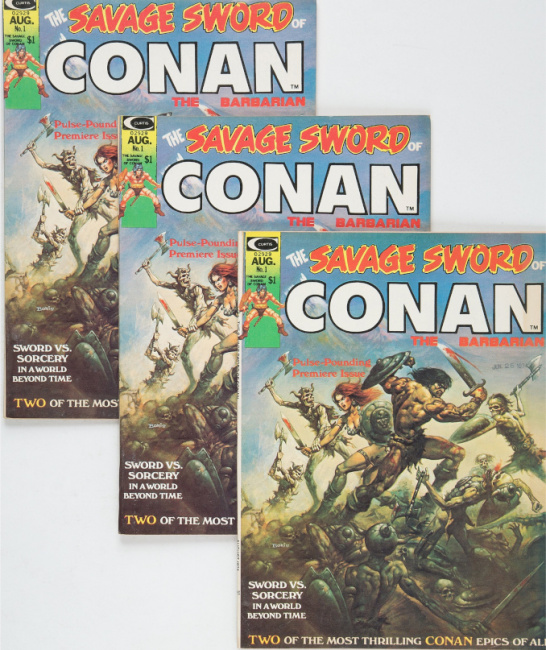

Example: A monthly order form from Seagate arrived in early 1974. This was a simple list, organized by publisher. This is also when first issues were a rarity. This month there was one from Marvel. This is the information on the order form:

Savage Sword of Conan #1, $1.00, shipping in June.

So I called my distributor. Hey Phil, what’s this Savage Sword #1? "It’s the first issue of a new Conan title from Marvel." At a $1 cover price, is it a magazine like Savage Tales? "Probably." Is it new or reprint? "Not sure." Okay, thanks Phil.

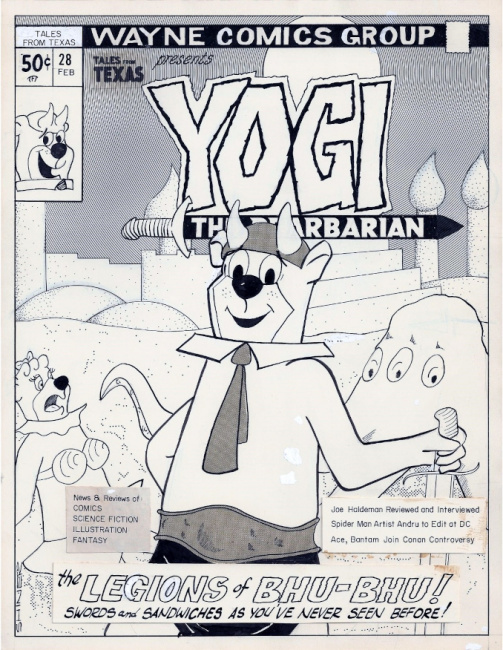

I was also part of putting out a fanzine called Tales from Texas at that point, because energy is wasted on the young. (The cover you’re seeing was by my co-conspirator Lewis Shiner.)

I called Marvel wearing my fanzine editor hat and asked what’s Savage Sword #1? "That hasn’t been announced yet! How do you know about it?"

Well I’ll tell you how I know about it right after you tell what’s in it. And I then strongly suggested they should announce new projects before they sent their production schedule to Seagate.

So publishers announcing titles and contents in advance of solicitation?

You’re welcome.

Example:

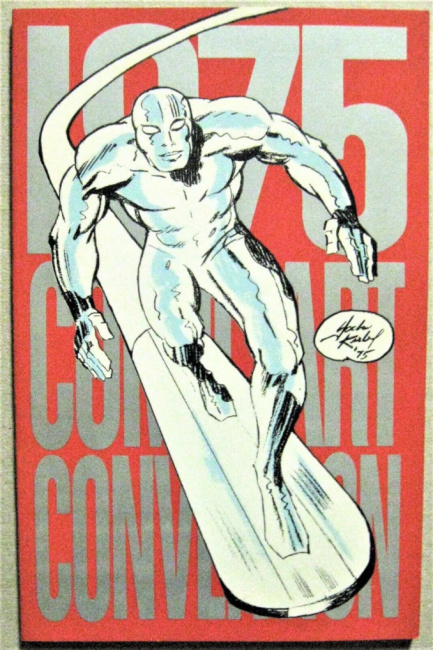

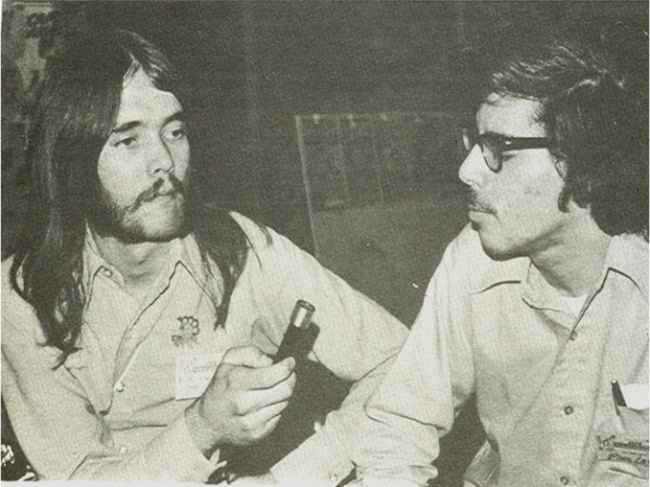

I made my first trip to New York City to Phil Seuling’s 1975 Comic Art Convention. I was now 21. It was on the traditional July 4th weekend at the Commodore Hotel, which I believe was thankfully demolished the following year. I wrote a review of the convention for Tales from Texas and sent my distributor (who was you’ll recall was also the convention organizer) a copy. In my review I mentioned a lot of the people I met for the first time at Phil’s con. Gil Kane. Roy Krenkel. Howard Chaykin. Michael Kaluta. Vaughn Bode. Walter Simonson. John Byrne. Barry Windsor-Smith. Jack Kirby. Jim Steranko. My future boss Paul Levitz. You get the idea.

Paul’s the one on the right.

I also mentioned that the hotel was in pretty bad shape and that there was a garbage strike in New York City while I was there. I had never seen bags of trash piled up to the second story of a hotel before. Piled up on every block. Seemed like something to mention in a con report. And I got that Secret Origins #1 I mentioned earlier.

We printed the fanzine, and I mailed a courtesy copy to Phil. About a week later, I received a phone call from my distributor. A very loud phone call, as Phil apparently didn’t quite understand how long-distance calls worked, and he wanted to make sure that I could clearly hear him.

The polite version of the call from Phil was that Phil was *ahem* strongly concerned that my review was making both him and New York City look bad. I made the unfortunate decision to reply to Phil that perhaps a mountain of rotting garbage on every city block was partially to blame for making things look bad.

Phil did not appreciate my critique of his conversational points. But he did keep selling me comics. This has always been my baseline for understanding retailer/distributor interaction.

Eventually I expanded from convention sales to brick-and-mortar retailing. But with my finely honed skills in distributor interaction, I eventually returned to publishing.

In 1987 I moved from Texas to a job with DC Comics at 666 Fifth Avenue. Which by the way led to a few awkward conversations at conventions: "You publish a comic called the New Gods? At 666 Fifth Avenue? Don’t you realize your address is the Number of the Beast?" Luckily the offices moved two times while I was on staff before I retired in 2015.

Now I’m a consultant in the comics industry and I serve on the Board of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. So I’m still involved with comics.

Our field has seen a lot of changes in the sixty-five years since I started reading comics. One change in our industry to me is inarguably for the better, so let me be clear: I believe that inclusion is important to the future of comics, and I believe in the power of diversity and representation in storytelling. I don’t believe that the future of comics should be based on how they looked when any of us were children. This doesn’t mean that I don’t appreciate the comics of my youth. Or yours. I literally have a house full of those comics. But that was our youth, and I don’t want us to impose our nostalgia, or anyone else’s, on today’s readers. They deserve to enjoy comics that reflect their world, not our past.

So this is my suggestion to you: If you aren’t carrying comics and graphic novels for a diverse audience, I suggest giving it a try. Have a featured shelf. Ask one of your employees or customers to curate it. And if you already are? Keep it up!

One of my rules from when I was a retailer applies here: You don’t have to like it to sell it. It’s not for you. It’s for one of your many customers.

There’s plenty of room for all types of comics and all types of comics readers.

As always, I’d like to thank my mother for never throwing out any of my comics. And for one other thing.

When I was a kid, and bored with that "Run Spot Run" stuff, my mother took me to the library. I was allowed to roam the entire place. A librarian saw me and said, "Shouldn’t you be in the children’s section?"

"No," I replied. "My mother says I can read anything I want." On that visit, I checked out a book on how to build a treehouse. Not a kid’s book, but an adult how-to book. Which I then started reading at my grandparents’ house. My maternal grandfather saw the book, and then built us a giant treehouse. All because no one stopped me from reading whatever I wanted to read. So if you wonder why I support the work of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund and the freedom to read… that’s it.

So in conclusion - don’t tell me or anyone else what to read, enjoy and collect.

I had a treehouse and an annoyed librarian to prove it!

And for a lot of readers, with Maus, Fun Home, Gender Queer, and so many others under attack, the stakes are a lot higher than my damn treehouse.

Thank you for your time.