Being a comic collector was a tough slog in the early 70s, but when the first comics direct distributor came along, it changed everything: collecting comics, selling comics, and comics themselves. We talked to three comic dealers from around the country in the earliest days of the Direct Market to learn more about its origin and its impact on the hobby and their lives. All started very young and went on to long careers in the comics business, helping the Direct Market they’d seen birthed grow and transform over the decades.

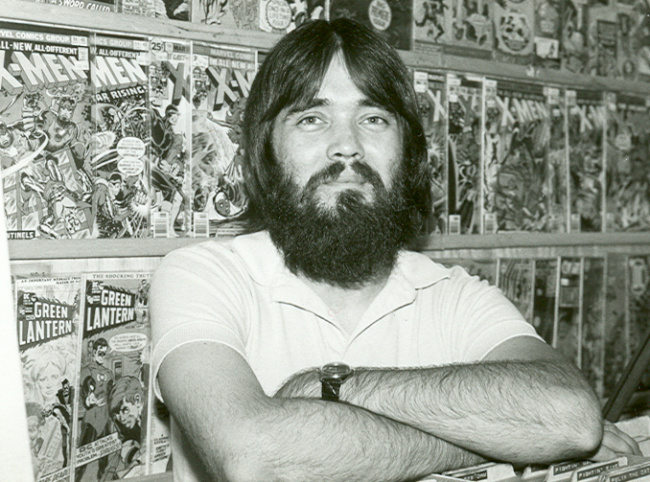

Greg Goldstein was a convention dealer in the early 70s, went on to a long career in the trading card business, and most recently was President at IDW Publishing.

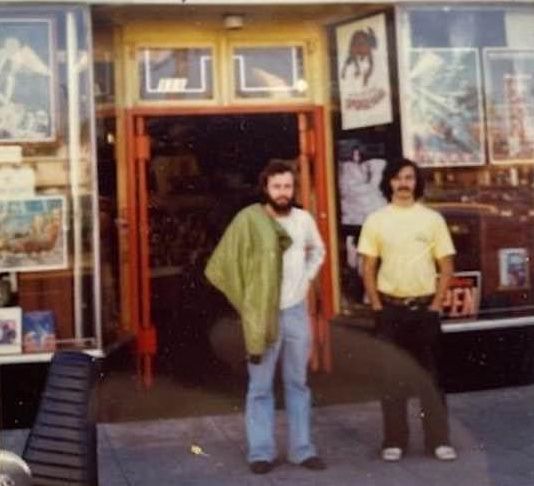

Bill Schanes and his brother Steve sold to friends and via mail order in the early 70s, opened stores in San Diego, started a distribution company, and started an early independent publisher; Bill went on to work for Diamond Comic Distributors as Vice President Purchasing for decades. [For the full interview with Schanes, watch the video interview (see “ICv2 Video Interview: Bill Schanes”) or read the transcript, in three parts (see "ICv2 Interview: Bill Schanes, Part 1," "ICv2 Interview: Bill Schanes, Part 2," and "ICv2 Interview: Bill Schanes, Part 3").]

Bob Wayne was a convention dealer in the early 70s, was a partner in multiple stores in Texas, and held a variety of positions at DC Comics over decades, finishing as Senior Vice President – Sales.

All three bought comics wherever they could find them as they started out, and found filling the needs of collectors that were having similar difficulties finding their favorites a way to make extra money. Trying to navigate the distribution system for comics, which had local ID wholesalers servicing stores in their territories with returnable comics, magazines, and paperbacks (see "Why Is Called the ‘Direct Market?’"), was a challenge.

Bob Wayne noticed that in Fort Worth, Texas, not all stores were getting the same comics. "Some outlets had one spinner rack and that was the basic DC and Marvel stuff, and some Harvey stuff," he explained. "You really wanted to find a retailer who was moving enough comics that they had two spinner racks, because those were the retailers who got everything. You would not have known that a lot of things even existed if you were only shopping at some place that only had one spinner rack."

Wayne was buying comics new and old to meet future demand. "I would just cherry pick what I found in used bookstores or even on the newsstand, based on my youthful assumptions of what people were going to want later or overlook," he told us.

All three frequented flea markets, garage sales, used bookstores, and other venues where comic collections occasionally passed through, sometimes finding a big score. Schanes described biking to a San Diego flea market in 1971 as a 13-year-old with his 17-year-old brother Steve where they ended up buying about 1,000 comics from a woman with a surfer van for $50, which kicked off their back issue business. By the end of the next weekend, they’d sold over $1,000 worth of comics from the collection to local collectors and were in business as comic dealers.

The first comic conventions were starting to emerge, and that was a place to find comics they needed and to sell to like-minded collectors. As a teenager, Goldstein started setting up at Phil Seuling’s monthly shows. He described his customers at those events, "They were people like me who might have missed an issue on a newsstand, or maybe their local newsstand or candy store just never even got an issue."

All three of the people we talked great up in cities that were home to early conventions: Seuling’s monthly and annual shows, and Creation Conventions, in New York City; D-Con in Dallas; and, of course, San Diego Comic-Con in San Diego.

The 1972 Seuling July 4th convention in New York City was a watershed moment for comics fandom. "That was just a giant event where there were a lot of creators and publishers," Goldstein recalled. "Just New York still being the central pub of comic book publishing, it just seemed to be that everybody I'd ever heard about or everybody I'd wanted to meet somehow was at the convention. To this day, when I opened my little autograph section of that book, I'm stunned at 12-year-old Greg and who I managed to meet and talk to."

Eventually, some comic dealers made their way to the local ID wholesalers to buy new comics. Wayne described going to both of the local ID wholesalers (for Fort Worth and Dallas) with friends who were paperback rack jobbers to buy new comics and magazines.

After they opened their store, the Schanes brothers (still in their teens) became big comics customers of San Diego Periodicals, the local ID wholesaler in San Diego, which eventually led to problems. They were hitting the ID warehouse the first day the new comics hit the packing line, picking the comics in good condition (not the ones on the outside of the bundles of 50 as they came from the printer) and getting the titles they wanted in the appropriate quantities.

"We started buying some books there and more and more books there," Schanes said. "It ended up being we were buying about two thirds of all the comics being shipped to San Diego."

With their bigger volume, the Schanes brother were able to talk the local wholesaler into giving them 25% off, better than the 20% off they gave most comic accounts. Then they made the mistake of asking for 30% off. "I’m not doing it,” the local wholesaler told them. "In fact, I don't want to sell to you anymore." When they asked how they could get comics, he jokingly told them to call Marvel and DC. The joke ended up being on the ID, as by that time the publishers were referring comic accounts to Sea Gate Distributors, the new company set up by Phil Seuling and Jonni Levas.

Goldstein remembers when he first heard about the idea for the new company at one of the Seuling shows in New York. By the time of the release of Shazam #1 (cover-dated February 1973), there were people chasing copies at outlets served by the local ID wholesaler. "Anybody who was anybody trying to either buy or sell comic books went to their local newsstands and candy stores and tried to buy them all up," he explained. "It was obviously not just myself and my friends in the town of Long Beach, New York, but it was other people doing this too."

With that kind of demand for key issues the time was ripe, and by late 1973, Sueling and his partner, Jonni Levas, had made a deal to buy DCs direct from the publisher (see "Phil Seuling: The Man Who Invented the Direct Market"), and were starting Sea Gate Distributors, Inc.

Goldstein, 13 years old at the time ("I was a little punk," he says), remembers Levas telling him about the new company. "Jonni Levas, who was an ex-student of Phil’s (and ultimately they became involved in a relationship) was walking around with a clipboard at one of these monthly conventions and said, ‘This is what we're doing. It's going to be called Sea Gate Distributors.’"

DC Comics and Warren Publishing (Creepy, Eerie, et. al.) were the publishers on the first monthly Sea Gate order form, with Marvel added within a few months. Goldstein ended up being account #006 of the new company, which was selling to his tiny account at 40% off with five copy minimums for the titles he ordered.

Then everything changed, with Sea Gate’s customers able to reliably get the comics they needed, and getting them weeks before the newsstand. Even though that was a big improvement, there wasn’t much information coming through from the publishers at that point. Wayne, who was Sea Gate customer #40, described the order process. "Every month, you would get basically a very simple printed list in the mail that would have, organized by publisher, it would be the title, the issue number, and the cover price, and you knew you were going to get a 50 percent discount," Wayne said. "That was all the information you had. I remember calling Phil when Savage Sword of Conan #1 was listed [August 1974 cover date], saying, ‘Can you tell me something more about this?’ He was like, ‘It's Conan. It's a number one. What do you need to [know]?’"

The transition to Sea Gate wasn’t always smooth. Schanes, who said of San Diego Periodicals, the local ID wholesaler, "They were heavy-handed and they were ruthless," suffered retaliation after the move away for the local wholesaler.

"My brother Steve had given me his first-year Honda car," Schanes said. "They were very, very light, almost like the early VW bugs. Four people could pick up a Honda car, four people—not weight lifters, just four people. All of a sudden, in my freshman year, all my tires were getting popped every day. I was getting four flats every day. Sometimes, my car would be moved to a different parking spot with four flats. I parked in the high school parking lot over here, but the car was on the back side of the school when I got out of school that day. They were sending a very distinct message about how unhappy they were that we decided to leave."

His mother took him to the local police station, where he described what was going on and his fears about what might happen next. "’They're going to kill me,’" Schanes told the police. "’And this is the guy, this is all the owners of this company. If I die, go arrest them. I'm telling you in advance, they're going to kill me.’ I didn't even know what that meant. About two weeks later, my tires stopped getting popped.”

Intimidation wasn’t the only tool in the ID wholesaler toolbox. They were also a source of illegally sold back issues. Schanes knew Nick Scotto, a Los Angeles-area comic dealer who had a deal to buy back door comics from the local ID. "[IDs] were supposed to strip off the covers and then return the covers back to the publishers or the national distributor," Schanes explained. "The local IDs were so unscrupulous, they said, ‘Just trust us. We ripped the covers off.’ They were basically double dipping. They were getting full credit back from the national distributor or the publisher, and then selling them out the back door for wholesale prices. For them, comics were good business."

Direct distributors started to proliferate, in part because of the 50-copy ordering increments Sea Gate established to get 50% off. "On the poor selling titles, we had too many books," Schanes told us. "We had to have everything in our stores, so we had to find other stores to sell our extras to. With the excess books, we were starting to wholesale them to those comic book stores and some other swap meet-ers as well. Some people were going to swap meets selling comics, and we'd sell them all the excess books, maybe even at our cost (not at a profit, just at our cost) to get our money back. It made our stores more viable because we had every issue now. We weren't missing issues."

By the time Bob Wayne opened his first store in Fort Worth, Pacific Distribution was up and running, buying direct from the publishers, and he started buying new comics from them. "I was buying primarily from the Schanes brothers out of Pacific Comics, because I was trying to not leave a footprint with the local distributor, [Austin-based direct distributor] Longhorn [Books], so that people wouldn't know that somebody was buying up a lot of comics in the neighborhood and start wondering what I was doing," Wayne said. "I was trying to be as under the radar as possible."

Later as timing of delivery became more important, Wayne started buying from Collinsville, Illinois-based Glenwood Distributors. "Then I was a Glenwood account, and Glenwood was able to get stuff to me quick because of their proximity to Sparta."

The three early Direct Market comic dealers had different perspectives when we asked for their take on the impact of the Direct Market. Goldstein was surprised that the Direct Market became the comics market, at least for periodicals. "I don't think any of us would've predicted that the Direct Market would've become the only market to buy comic books at," he observed. "That was supposed to be additive and a place where collectors could go and not be worried about the wire marks on the comics or the candy store owner who didn't bother to tell the guy to bring this month’s Spider Man or any of that stuff. In my mind, I always saw it as an alternative form of distribution."

Schanes also noted the growth, and its connection to products produced specifically for the Direct Market. "Probably in ’71, there wasn’t 100 comic shops in the whole country," he said. "There might have been 20 or 30, or maybe 40." He remembered Dazzler #1 as the first direct-only comic, and a turning point for the business. "All the comic book guys were buying non-returnable, so we were a gold mine… "[Dazzler #1] might have been the very first item created from Marvel or DC just for the comic shops [March 1981 cover date – ed.]. That was a big breakthrough. That's when the comic shops' buying power as a collective came into fruition in a pretty meaningful way."

Wayne also noted the impact of the Direct Market on what New York comic publishers were publishing. "One of the things that drove change to me was when Marvel began experimenting with their Marvel graphic novel line, so you ended up with things with a longer shelf life, higher production values, and a way to showcase properties and talent. I think that made it more talent-centric, talent focused. I sold more copies over time of the first Marvel graphic novel, The Death of Captain Marvel [April 1982], than I did on a lot of periodicals that were coming in and out. It wasn't all the first week. It was more like week in and week out, people would just be coming in and buying that as long as I had them available. Having things with a spine and a long shelf life started to refocus everybody on how that could work."

This article is part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."