A sampling of stories on investment in the comic book industry suggests that there is an oversized investment in comics these days that is ambitiously targeting entertainment rather than publishing. ICv2’s Rob Salkowitz noted as much in his well-considered column (see "Who's Writing the Checks for the Golden Age of Genre Entertainment?"). He noted major capital investments by entertainment companies into comic book publishers Dark Horse and Valiant.

Many people who link their livelihood to their fandom have concerns when they hear of another entertainment-based investment in comics. Some, like Salkowitz, focus on the legitimate financial health of the industry if the investment is unsustainable. For some others, those concerns get wrapped up in geek-gating and fears that the financial influence and interest of "outsiders" will dilute "my" fandom.

Regardless, the current investment cycle seems consistent with comics investments of the recent past and may underestimate shifting market demand for comic book content.

Margin for "traditional" comic book publishers and retailers has always been thin. It is hard to make money in this business. Almost every creator and publisher today hope that their content finds a way to succeed in Hollywood and, by extension, pop culture merchandising where margins are greater. Also true, but less often discussed, is that a successful entertainment property in other media raises the profile—and sales volume—of the comic books themselves.

Marvel found its way out of bankruptcy in the early 2000s through media and merchandise investments and successes in film. DC Comics became a subsidiary of DC Entertainment in 2009 and, most recently, moved over to Warner Bros. Global Brands and Experiences division. These two comic book publishers account for nearly three-quarters of the comics sold in the direct market, but neither amounts to a rounding error in their parent company financials. Movies, merchandise, and video games might be discussed in their corporate filings, but publishing rarely gets a mention.

The influence of other media, whether investment or income, has never been limited to the Big 2. Dark Horse created Dark Horse Entertainment more than two decades ago and accessed the Fox lot through a first look deal as early as 1992, signing a first look deal with Universal Cable Productions in 2015. BOOM! Studios had a first look deal with Fox, before selling a significant stake in the publisher to the studio last year. IDW Publishing describes itself, a subsidiary of publicly traded IDW Media Holdings, as a "fully integrated media company." While its comics and graphic novels have struggled to make money quarter to quarter (see "IDW Publishing Division Loses $801,000 in Most Recent Quarter on Sales Increase"), its entertainment division makes money and it recently named a longtime TV and film executive who had been on its board as its new CEO to replace the founder and longtime owner Ted Adams ("TV Exec Replaces Adams as IDW CEO"). Oni Press has had a dedicated film and TV production arm for years with successes that included films based on its Scott Pilgrim and Coldest City books.

Licensed content from movies and TV bolsters almost all of the larger, independent comic book publishers’ sales. Image Comics stands out from this, but it functions very differently from most comic book publishers and both its partner studios and creators have published properties whose sales are heavily influenced by films or TV shows. There is nothing new about investment or capital in the comic book industry focusing on what most publishing agreements would describe as ancillary revenue opportunities.

The real issues for concern are whether that continuing investment, because of its focus on a return from entertainment revenue, is flooding the market with unwanted titles, driving down the prices of books, and driving up the cost of creation. If that were the case, publishers would be unable to support marketing of their published titles, cheap books would strain retailers’ bottom lines, and the ultimate unsustainability of that publishing model would drive publishers out of business and leave a vacuum for graphic literature that either further consolidates the industry or results in a new and disruptive paradigm.

There is a market for new content generated from ongoing investments.

Or, more accurately, there are markets. The frequent encouragement to let "the market" decide an issue is misleading because it often causes us to think in terms of a single market. But, we live in a world of many inter-related markets. Any single market, such as the comic book and graphic novel market in North America, might expand or contract. If that is the only market, then the rate at which that market expands would substantially determine how much additional investment the market could take.

But, within a given market, there are submarkets; and, those submarkets expand and contract. So, investment in one submarket may make less sense when that market contracts. It would make more sense to shift investment or make a new investment in a different submarket that is expanding. At the end of the day, new publishers and investors are making bets on new and shifting markets.

There are new markets for comic books and graphic novels. The Valiant and Dark Horse investment deals explicitly called those out. According to Mike Richardson, the Dark Horse deal started by looking for a film fund but grew as the possibilities to expand into the Chinese market and invest in retail became more obvious. He stated that part of the investment would go back to published content, but it sounds like most will go to making movies based on existing content (a different market) and extending existing content into a rapidly growing Chinese market (a growing market). Similarly, DMG Entertainment stated that its initial investment and subsequent acquisition of Valiant would allow it to extend existing content into merchandise (a different market), entertainment (a different market), and the Chinese market (a growing market).

Concerns that the North American Comic and Graphic Novel market is flooded with content are real. Direct Market retailers, at their trade associations and in individual conversations, argue that there are too many comic book titles. Knowing and managing the full range of titles creates operational burdens for Direct Market retailers. Local comic shops also struggle to offer the full range of content because individual stores have limited shelf space and limited opportunities to expand their existing customer base. The transaction costs associated with retailing more titles that sell fewer units are higher.

That does not mean that consumer demand for other titles is absent. As many in comics remind us, comic books are a medium, not a genre. The success of comic books as a medium has created audiences who are exploring comics in other genres than those that were previously accessible. Each genre is a different submarket. That means that even if the demand for comics were not growing, the demand in submarkets is shifting and new titles in growing genres feed that demand.

In addition, the largest investment increase in publishing comic books over the last decade is likely not from comic book publishers. Traditional book publishers are now publishing graphic novels at a growing rate and selling more than comic book publishers. Imprints such as Scholastic Graphix, First Second, and Abrams Comic Arts have launched best-selling graphic novels in the fastest-growing parts of the North American Comic Book and Graphic Novel market: book stores, mass market stores, book fairs and clubs, and online retail.

These expanding markets are eager for titles across all genres and for all ages. That creates demand for new and different titles. Major traditional publishers like Harper Collins and Random House are transitioning to meet that demand. The size and scale of those traditional prose publishers and their reasonably sophisticated business practices do more to put downward pressure on book prices than the number of titles on the market.

While changing technology and crowdfunding have made it easier for individual creators to publish their ideas—simultaneously putting upward pressure on content acquisition costs—there are significant barriers for new publishers attempting to enter "the market." Those are most notable in the Direct Market and sales of periodical comics, but whatever the source of those barriers, independent publishers who wish to compete must make substantial investments to overcome those barriers.

Are such investments good for the industry? I firmly believe that the best content and a strong comics industry needs new and different voices.

Geoff Gerber is the former President of Lion Forge Comics and has been counseling comic book publishers and entertainment companies for almost two decades.

Guest Column by Geoff Gerber

Posted by ICv2 on November 12, 2018 @ 4:35 pm CT

MORE COMICS

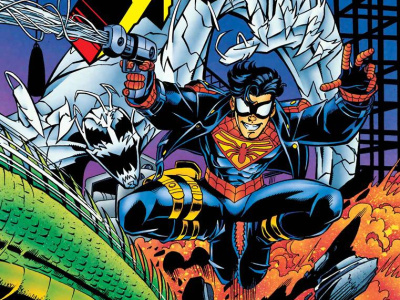

Part of 1996 Marvel/DC Crossover

August 1, 2025

Writer Karl Kesel and artist Mike Wieringo are the creative team for the one-shot comic, which was first published in 1996 in the middle of a Marvel/DC crossover.

Crowdfunding Campaign Launches in October, Followed by Retail Release

August 1, 2025

Vault will crowdfund the graphic novel on the Backerkit platform in October, then release it to retail.

MORE NEWS

In 'Dracula vs. Hitler'; New RPG Just Unveiled by Devir Games

August 1, 2025

Devir Games unveiled Dracula vs. Hitler , a new RPG, that will be heading to BackerKit.

For 'Cosmere RPG'

August 1, 2025

Brotherwise Games previewed their Stormlight Premium Miniatures Collection, for Cosmere RPG.