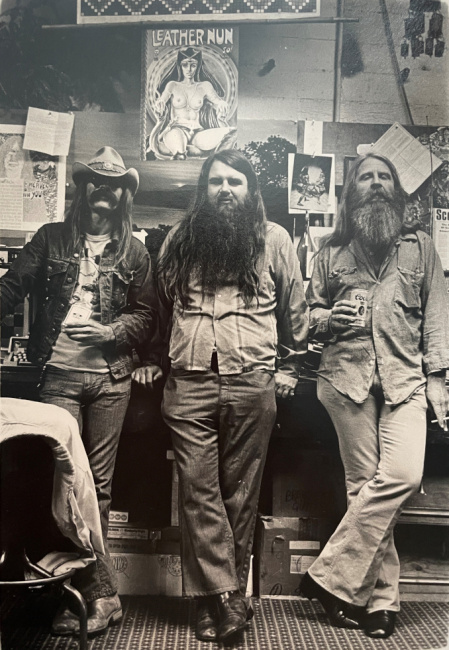

A Table Talk at Berkeley Con 1973, with l-r, Great Speckled Bird proprietor (un-named); Dave Moriarity, Rip Off Press; Denis Kitchen; Ron Turner; Don Donahue, Apex; Don Schenker, Print Mint

To watch a video of this interview, see "ICv2 Video Interview: Ron Turner and Denis Kitchen, Part 1."

This interview and article are part of ICv2's Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

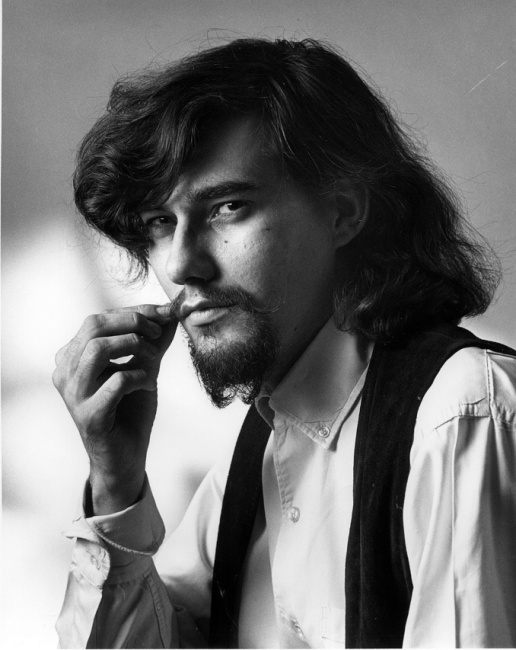

Let me introduce our esteemed guests: Ron Turner is the founder of Last Gasp in 1970. Last Gasp was and is a publisher and distributor of underground comix, manga, and art and pop culture books. Ron just released his first book, The Collected Stories of Ron Turner.

Denis Kitchen is a cartoonist and founder of Kitchen Sink Press in 1970, publisher of all kinds of comics including underground comix, comic strip reprints, and perhaps most famously, comics by Will Eisner. He is currently an art agent and packager.

I'm Milton Griepp, the founder and publisher of ICv2. I had early connections to both of these gentlemen. I worked in comics for two politically oriented distributors in the late 1970s—Wisconsin Independent News Distributors and Big Rapids Distribution Company, and co‑founded Capital City Distribution in 1980. We did business together when I was in distribution and they were publishing. I remember those years fondly.

Let's start out back in that period. I want to ask you both, how did you get into publishing comics? How did you distribute your first title? How did you get it to stores? What kind of stores were you selling it to? I guess the first publishing might have been Moms. That was '69. Right, Denis?

Denis Kitchen: Right.

Why don't you go ahead and talk a little bit about that? Then I’ll ask you the same thing, Ron.

Kitchen: Sure. I self‑published Moms Homemade Comics #1 in Milwaukee, thinking it was pretty much a regional publication, but copies got out. 500 went to Gary Arlington's San Francisco comic shop, and 500 went to Woodstock, but 3,000 of the 4,000 sold on the East Side of Milwaukee. After Gary Arlington sold out his 500, he ordered more, and I said, "I don't have any more. I spent the money." I lived like a king all summer.

One of my roommates was headed out to San Francisco and he said, "Oh, I'll find a publisher." Ron hadn't started yet. Rip Off [Press] had just arrived in town. He went to the Print Mint and they said, sure, they would be happy to reprint #1 and do the second issue I was already partly done with.

That would have been fine. I wanted a publisher. I just wanted to be a cartoonist. The problem was I never got what I considered a proper accounting from Print Mint. They would send a check occasionally with no statement of how many they printed. "By the way, what percentage am I supposed to get?" It just didn't seem right, and so I decided I'm going to self‑publish again. I mentioned it to Jay Lynch and Skip Williamson shortly afterwards when I saw them in Chicago, and Jay said, "We had problems with those guys too." He said, "If you're going to publish your own, would you publish Bijou Funnies also?"

I foolishly said, "Sure. Two is as easy as one," and that's how I became a full‑fledged publisher.

OK, Ron, why don't you tell us about your first publishing experience and how you got your first books out?

Ron Turner: Mine came from a New Year's Eve party. I think it was New Year's Eve, '68. I was working at a Kaiser hospital then, doing studies in allergies and emotions, and my coworker had a New Year's Eve party.

I was also finishing up a graduate degree at San Francisco State in experimental psychology. We ended up having a big strike there for the Ethnic Studies department to have a Black student union and curriculum. Reagan didn't like that idea very much. He was our governor then. So it got very involved in political things, and I was already involved. My girlfriend had worked in Delano with Cesar Chavez and [was] roommates with Dolores Huerta. I'd also been involved with and actually [was] a dues‑paying member of the United Farm Workers Union. I was political at the time; at least I thought I was.

Another friend of ours, who used to run the presses at The Delano [Record], was running them at the Berkeley Ecology Center for free, basically, Rod Friedland. We used to sit around and get stoned on the weekends. His girlfriend was a sister of my girlfriend's best friend. We’d just get stoned and come up with ideas about how we were going to win the revolution and stop the war and the usual stuff.

What happened was, of course, like every other good thing that was happening, it needed money to survive, and the first ecology center in the country needed funds. We thought, why not do an underground comic on ecology? That could be a benefit book for them. They were all excited about that. The guy, Marc Lappé, was running the ecology center at the time. His wife had written a book called Diet for a Small Planet. We were touching elbows with the hoi polloi of the alternative movement at the time, and thinking we were doing a good thing.

That went on, and we kept having meetings. I hated meetings. I couldn't stand meetings anymore. I finally said, "Look, I'll do this project, but I can't answer to anybody. Anybody else want to do it?"

Nobody.

"Do you mind if I do it?"

"No."

"Do you mind if I be...?"

"No, just do it."

That's fine. I did it, and. I'd already been buying my underground comix from where my friend had bought his, from Gary Arlington [his store was San Francisco Comic Book Company]. I got the whole background of all the politicos at San Francisco State, the Black Students Union members, and whatnot, reading comics at night there for relaxation after a hard day of being chased by the 2,000 cops that were on campus every day, plus 30 horseback cops plus several helicopters. I realized there was something more in them besides just the Freak Brother jokes when I had Radical America Komiks, and I realized that all the African American guys thought that Smiling Sergeant Death and his Merciless Mayhem Patrol, and especially Watermelon Jones, wasn't just a stereotype, but they understood that it wasn't directed at them, it was directed at the way the culture saw them and how wrong it was. They laughed along with me, not against me or found my laughter in poor taste. I thought, "This medium has something to do." That was part of the reason we came up with the idea of doing the ecology comic.

I'd known a few people because my next‑door neighbor in San Francisco was Randy Tuten, and he was a poster artist for Bill Graham and Chet Helms. I met a lot of the poster artists back in the day, and Greg Irons became my best connection to the artists, and we started having meetings. I didn't know what I was doing, so I just asked them, "What do you guys want for a page rate?" There's big discussions, and finally we arrived at what they wanted to get per page, and I extrapolated out how many comics they had to print in order to make the page rate worthy.

The other lesson I learned real quick was you don't allow any liquids in the room when the original art is around. This funny thing about how a cartoonist can knock over somebody else's wine glass near their artwork, [laughs] very odd. We banned liquids in the room after the first meeting.

Then we somehow pulled it all together and did it all and we got it printed up, and coming out of the bindery, John Plowman's bindery. John Plowman was a member of the John Birch Society, but he was one of the few people that had a bindery in the Bay Area who would staple and trim our comics. He was a believer in that the government or nobody had any right to tell you what you could think or couldn't think, so even though he hated us (he had little flags in every station in his bindery), he would print it. He would do that job. I came back with 20,000 copies of Slow Death Funnies #1, and drove over to Berkeley Ecology Center and said, "Here's your comic book."

In the few months from the time that we started doing this till that moment, virtually everybody I knew at the center had left because Washington, DC, had decided it understood what ecology was and was starting to fund programs. The requirement was basically that you could spell "ecology" correctly, and you could get a job. Everybody that had been in all these places working for nothing all of a sudden had a job in state governments and national governments if they wanted it. The new crew that came in, they took a look at it and said, "Huh, well, we'll take 10 for our bookstore."

Now, in order to get this stuff printed and paid for, since I didn't have any money… It was like Willie Sutton once said when asked why he robbed banks, "Because that's where the money is." In Berkeley, where was the money? The drug dealers. I met up with some drug dealers that I knew and was introduced to other drug dealers that they knew, and I shook them down: "What have you done lately for your community? Surely you have profits and surely you want to invest in them." And they did.

When the ecologists said, "We'll take 10 copies," and I'm stuck with 19,990 of them, I was going to have to sell those and pay back these drug dealers because nice as they were, there was a certain history of people who unfortunately crossed drug dealers for money. I didn't want that on my conscience.

I just figured out, "Well, how do you do it? You distribute. Gee, distribution. What the hell is that?" I went down to Print Mint and they took a pile, and I went to Rip Off Press and they took a pile. Two or three months later when I went to get paid, they said, "We don't have any money."

I said, "Well, you took my stuff and you sold out and you want more, what's going to happen?" They said, "Well, why don't we give you our comix?" I thought, that's not a bad idea because they had the Freak Brothers and Zap, which were the biggest sellers of all. I took those. They put a caveat which said, "Fine, but you can't sell in any of these places," and they listed all the best places to sell. This meant I still had to go out and find other places to sell. Nixon had cut off all the funds for what my project at Kaiser was, so I was without a job and income. So I had time on my hands. The strike at State was pretty much over and we failed. Everybody was very bitter and I wasn't going to go back there. I had time on my hands. I said, "OK, so I'll figure out how to do this."

I’d just go around to any place I thought looked cool and interesting, or maybe a little alternative, and ask them if they would sell these comics for the ecology center. Or something like that. I ended up with comic books being sold in a very fancy leather shop on Union Street called the Dead Cow. They took a whole bunch. Beauty parlors took them. Anything to attract more customers because they saw that it was an item of great interest to a lot of people. Or as Robert Williams once wrote, going down from top to bottom on the margin of Forbidden Knowledge Comics that George DiCaprio and I put together, "Curious your attraction to this unclean thing."

Basically, they were. They were excited about that. I went down to the Whole Earth Catalog people in Palo Alto and met Stewart Brand and all those folks. Everybody was greatly in favor of this stuff, and the sales went, and a few months after I started that, it seemed like that was something I was doing for the moment. At least it was giving me a few dollars in my pocket.

Then I wanted to do a comic book, a feminist comic book. I wanted to do It Ain’t Me Babe. Trina Robbins, I was told, already had a comic book that she was looking for a publisher for, so I called her up and I went over there with a check for a grand and she handed me this comic book with one hand because she was carrying the baby Casey in the other. The second book was a harder sell because it was all women, doing stuff about women, and probably only at that time, maybe only 5 percent of Gary's customers, he told me, were women.

Gary's customers at San Francisco Comic Book Company?

Turner: Yes.

Let's work our way into the '70s. That sounds like that was all local, Ron. Denis, maybe you could talk a little bit about how you started publishing more titles through the '70s and had to expand your reach. How did you do that? What kind of stores were you selling to? When did comic stores first come into the picture?

Kitchen: Well, basically like Ron, when I started in Milwaukee, I went to the obvious, the low‑hanging fruit was head shops, of course. Used bookstores, the kind of gift shops that appealed to hippies back then. But as you note, that was strictly local.

Coincidentally, I had co‑founded an alternative weekly paper called The Bugle American based in Madison and Milwaukee. When an underground paper joined the Underground Press Syndicate, one of the requirements was you traded comp copies with other members. The Bugle would get at least 50 or 60 underground papers in the mailbox roughly every week. A lot of the staff members had no interest in them. I would rifle through them and I would clip all the ads for the head shops or gift shops that looked like they would be potential customers. That's how I put together my first mailing list. It ended up being pretty nationwide.

I always say, I didn't start out a very good businessman, but when the demand exceeds the supply, anybody can succeed. In those days, the undergrounds were very popular and we had no problem selling.

The other thing I did that was very naive, but it worked, was I gave credit to everyone. I didn't think hippies would rip us off. We'd send a shipment net 30, and we almost always collected.

It might take more than 30 days, but we were dealing with members of the same tribe, and there really was a feeling early on that you were joined at the hip in a cultural way.

That's how it expanded out of Milwaukee. Then eventually, there were distributors involved. Initially, in my case, it was right to retailers, and we also developed a mail‑order catalog early on, selling directly to individuals, and that was a separate mailing list.

Were there any comic stores at that time, or were you selling to any in the '70s?

Kitchen: They were rare. I think after Gary Arlington, there was Bud Plant and his partners had that small chain in the Bay Area, and then they popped up. They popped up, but it took a while. Someone else would have to chart that.

The head shops you were selling to, like Monkey’s Retreat was one of the ones that I remember from mid‑'70s, that was kind of a crossover store, I think. They ended up doing color comics, but I think they started in undergrounds and stuff, didn't they?

Kitchen: That sounds right.

Ron, what were you seeing in terms of trying to expand out of the Bay Area with your distribution?

L to R: Dick Dirrette, Ron Turner, Geoff Watson. Shipping department at Last Gasp, 2180 Bryant Street, SF. About 1973.

I was also involved with a group called the Committee of Returned Volunteers. We were all former American Friends Service Committee or Peace Corps volunteers. You had to have worked for no money in a foreign country for two years in order to be a member. In terms of the movement, we were like the State Department of the anti‑war movement because we could tell, virtually almost every country in the world, what was really going on there. Almost everybody is pretty left‑wing, although there's a few right‑wing people who were members of our group.

I went across twice, passing out underground comics. I used to get, from Bill Graham and Chet Helms, big stacks of Fillmore posters and Family Dog posters, put them in the back of my Volkswagen and cases of comic books. I'd pull into some small town in the Midwest, for instance, like in the middle of the night, and just leave them out by the Dairy Queen, Sonic or whatever was there at the time and drive off. I was kind of a little Johnny comic seed there. That was a lot of fun.

Click here for Part 2.