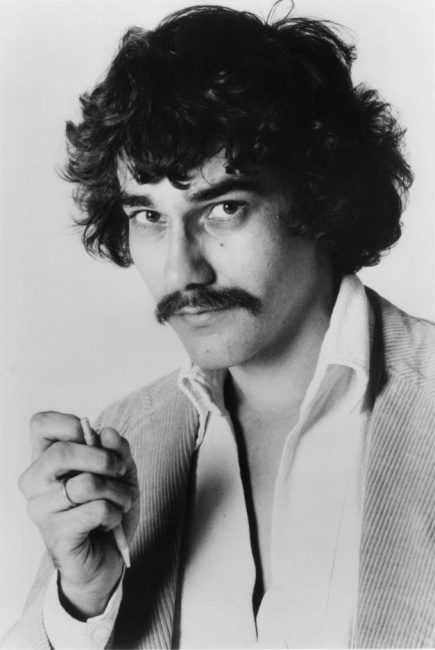

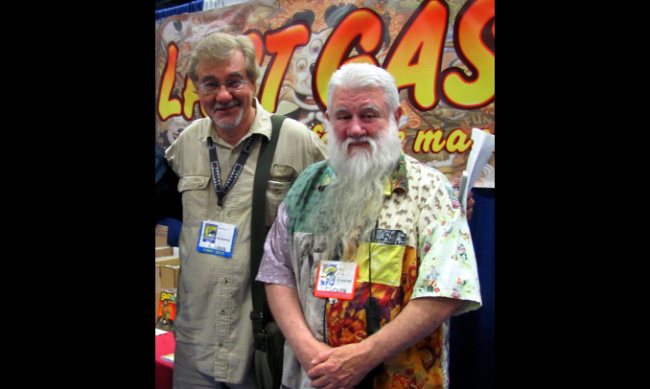

Our history of the Direct Market continues with a conversation with two publishers of underground comix, Ron Turner, founder of Last Gasp, and Denis Kitchen, founder of Kitchen Sink Press. Both Ron and Denis were distributors as well as publishers, and both started their businesses in 1970. In Part 2, we discuss the evolution of the underground comix market as well as Denis's shift toward non-underground comics at Kitchen Sink. Part 1 of this interview focused on the early days of underground comix, the early 1970s. And in Part 3, they talk about the very early days of manga publishing in America and the drift toward the book channel.

To watch a video of this interview, see "ICv2 Video Interview: Ron Turner and Denis Kitchen, Part 2."

This interview and article are part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

Were there any comic stores in the Bay Area [in the 1970s]? San Francisco Comic Book Company, I think, a lot of people think, might've been the first comic store in the U.S. Were there starting through the '70s to be more, Bud Plant’s and others?

Turner: Yes, Bob Sidebottom's Comix Collectors Shop down in San Jose. As you said, Bud Plant and his bunch had Comics and Comix. One spelled with a "cs," and one spelled with an "x." They began popping up.

Gary told me when I met him in about ’68, '69, that he had been working in an Arab record store nearby. He was living still at home in Hayward where his dad had a lumberyard. The dad was getting out of the business and selling the house and kicked Gary out, and Gary had to move all of his crap. Instead of moving it into storage, he founded a retail store and started San Francisco Comic Book Company as a result.

Denis, when did you become aware that there was a color comics distribution network forming?

Kitchen: I don't know that I can pinpoint the date. Early on, not knowing eventually there would be a pretty organized distribution system, we were flailing about trying to solve the problem ourselves. My first partner and I bought a used police paddy wagon. We hired somebody and it would make the route, basically most of central and southern Wisconsin and into Illinois, Chicago in particular. We would just fill it with comics and he would just make stops, drop off books, collect from the invoices. We thought eventually that would just grow and we'd have trucks plural. Then I think whether it was WIND or what was the one out of Michigan?

Big Rapids?

Kitchen: Yeah.

Donahoe before that.

Kitchen: Yeah. I know they reached out to us and we thought, "Great!" We just had to work out a little bit different discount. A shop would get 50 off, but a distributor would get 60 off. We figured out, OK, there's still enough in the pie. There's some margin and there's efficiencies in large quantities.

What I don't think we could have anticipated was that then there would be more and more distributors who would specialize in comics. The color comics market to me was a whole other world. I didn't think we'd ever overlap because I had been told by everyone that newsstand comics and publications in general were "controlled by the mafia," if not formally the mafia, guys you didn't want to deal with. We never wanted to deal with the newsstand guys.

How about you, Ron? When did you encounter this color comic distribution network?

Turner: Well, Mike Friedrich was around and he was publishing comics like Star*Reach and maybe a few others. They were alternative comics, but they really weren't undergrounds, so we used to call them Ground Zero.

Ground Level?

Turner: Ground Level, but we called them Ground Zero. [laughs]

OK.

Turner: We're not nice. He went back to work for Marvel and Phil Seuling had had his problems with being busted for Zap Comix being sold at one of his Sunday comic fairs in New York. He was a high school teacher and he lost his job over this stuff. He was trying to figure out what to do and he was terribly into comics. I remember that Mike figured out how to help him to set up as a distributor, but then Mike also got a job at Marvel, I think it was, and they were talking about this area called the Direct Market.

Whereas the newsprint people, the guys who were doing distribution to newsstands, they were mafia. They would go in and they’d tell somebody like a drugstore guy, "OK, you're going to carry magazines now." The guy says, "What do you mean?" He says, "Don't ‘what do you mean,’ you're gonna carry them now. Isn't that right, Lefty?" And they would suddenly have books and comics and magazines and stuff in their pharmacy. That's how they got all around. The reason there's a date on the magazine is, that's not the date that it's coming out, it's the date that it's expired. That's when they pull all the magazines off the shelf. If it's July and they see a July on it, it's time to go, because the August one is available. Would they ever get a chance to count and see what they actually sold? No, the guy would hand them a bill and say, "Here's your bill. Pay it."

I've been working on these dates, Ron. I think Seuling started buying from Marvel and DC in late '73. Marvel might've been early '74. I think Friedrich went to New York around 1980 and worked for Marvel then. The relationships of those direct distributors predated his arrival there, but he did set up the first formal trade terms (see "ICv2 Interview: Mike Friedrich"). Marvel's terms were a mess and Friedrich helped set up those as there was a system for dealing with these distributors. Did Seuling buy from you, either of you, Denis?

Kitchen: Oh, absolutely.

When did that start?

Turner: Early.

Kitchen: Yeah, I first met Phil in person in '71 at one of his conventions. He already had a table full of undergrounds that he had gotten from, I think, all four publishers by then. He was a big supporter.

I think even when he did his deal with Marvel and DC that really changed things in a profound way, he had started out with the alternative titles because I remember he had at least two tables put together, like 12 feet of every underground property that was in print at that time. I can't think of anyone else aside from Bud Plant early on who had been that supportive and who had the reach.

Ron, were you on those early tables that Phil had up in the early '70s? Were you selling to Seuling?

Turner: I think so, yeah.

OK. And also to Bud, right? He started distribution then in the '70s also, right?

Turner: Yes, they had their little store and then they had—Bud was multi‑level. He had a big collector market for his stuff, plus he had the retail stores and as a distributor, he could get stuff for the stores at distributor prices.

Same thing went for Steve Geppi, it was the same situation, if you could get enough stores to become a distributor, then your cost of merchandise simply beat out your competitors’ a lot.

I started at WIND in 1976 and there were a handful of comic stores around the Midwest by then. They were doing undergrounds at the time and the reason they hired me was because they were starting to do color comics and I knew a little about that because I'd gone to a couple of conventions with a friend of mine.

By that point, at least for those distributors, there was crossover and we were not only selling color comics into old underground outlets like record stores, we were also selling undergrounds into places like newsstands, which might've never carried them before. They had limits on the kind of stuff they would carry, but certainly the tamer titles that didn't have as much sex and violence on the cover, they could stock. So at least by the late '70s, I was seeing some kind of crossover between these different kinds of stores. Were you guys seeing that? Denis?

Kitchen: Oh, certainly by the late '70s. Absolutely.

What were some early comic stores that you were dealing with?

Kitchen: I had a head shop myself on the East Side of Milwaukee called Strickly Uppa Crust and we had two spinner racks with color newsstand comics, but then we had a whole wall of undergrounds. We advertised ourselves as having the largest selection of comics in Wisconsin. No one ever challenged it.

If you came in, if you wanted Spider‑Man, you'd find it, but if you wanted Zap or Freak Brothers or anything else, we had it all. I remember early on, I wouldn't be there, but the manager would say later, "Oh, Lou Alcindor came in last night and bought comics," or "John Mayall was in town, gave a concert and he showed up and bought comics." We started thinking, wow, this really is not only a phenomenon, but we're attracting more than just hippies who live here. This is a cultural thing that I don't think anybody had a really good handle on.

Other than carrying the color comics ourselves in a store, I didn't feel a connection at all. I remember Seuling early on when he was starting his system, he called me, and he asked me if I wanted to handle Marvel and DC in the Midwest. I was like, "Ah, I don't like those comics anymore." He said, "No, no, no, no. You can make money doing it, big money." I said, "Phil, I just don't like those comics," and he said, "You're not listening to me!"

I said, "Phil, I don't want to get involved. That's a whole other business. I don't want to do that," and he said, "Goddammit!" and I remember he hung up.

Turner: He never asked me.

[laughter]

Kitchen: Well, maybe you didn't know Phil, whatever. That would have been what, '73, according to Milton.

Turner: Well, the Berkeley Comic Con was in '73...

Kitchen: Right. That pulled a lot of people together.

One of the things Ron mentioned earlier was he couldn't collect money from Rip Off, so he got comics instead, but you and I swapped a lot. We swapped tens of thousands of comics all the time, thinking I could sell more of yours in the Midwest, you could sell more of mine on the West Coast. We did that for a long time.

Turner: Sure, and it worked out favorably for both of us.

I used to swap with Ron also. Big Rapids would buy out a print run or something or have some comic that he didn't have. We used to swap from time to time also. That was definitely an established way of doing business.

Ron, what were you seeing in the late '70s? Were you starting to see more comic stores pop up, and were you dealing with more stores out of the Bay Area?

Turner: Well, that, but also the head shop had become our big seller, too. Originally, comic books got their whole discount from Print Mint who were selling posters. They tagged along to all the head shops with the poster sales. That's where the discounts came in, similar to what the posters were selling for.

Many people don't know, but Print Mint had an outlet on Haight Street during the beginning of the Haight‑Ashbury days, plus the place they had over in Berkeley. They'd hired two people who had come from the Farm Workers Union gatherings, Bob and Peggy Rita. Eventually, Bob Rita and Peggy became the owners of the Print Mint. They did get into some trouble with their money. It was just very sad that that was true.

By the mid‑70s, I remember Crumb was having some problems with them and since he had two comics, Zap #0 and Zap #1, which are all his, so he didn't need permission from the gang that he brought in to be part of his Zap Comix, he asked me if I could take them over and do those. I said, "Sure!" Then the whole group was having problems with Print Mint and they were having a hard time paying their bills and I needed Zaps a lot, so we worked it out that one of us would pay royalties and the other would pay the print bill. I think I was paying the print bill, and they were still supposed to do the royalties.

After a couple of years of doing that, everybody else in the Zap crew said, "Can you do our Zaps?" I said, sure. They were odd because they demanded a few more percentage points for royalty than anybody else did, but that was OK. The volume that we were selling was—the heyday was over, but there was still lots of interesting and incredible stuff they were doing.

We then had a little bit more of a market. You almost had to have Freak Brothers and Zaps to be in the business. It was kind of a guaranteed sale if you had those comics. Somebody would buy those. You would never have to worry about those not selling.

I found a list in the '90s when we got our new building. I remember explaining to people as the number of distributors had declined, in the '80s I had a list of 30 places where I could sell these out to distributors around the country and in Europe, the comics. I think when I was showing the staff this, it was because now it was down to three or four distributors that were left.

Where we started making our bigger sales were to the head shop distributors, those people who were selling pipes, coke screens and bongs and whatnot. At the same time, I’d become partners in a laboratory supply firm. We were selling a hell of a lot of Ohaus scales and we invented a Paraquat test kit because the government was spraying marijuana fields with Paraquat, and we didn't want our customers dying, so we had a Paraquat test kit, which meant we had to buy a lot of thermometers and glassware. Half our warehouse was full of head shop stuff.

The biggest distributor was a guy named Marty Milmann from Philadelphia and he had a group. His organization was called Merchandising Service of America. He had thousands of head shops that he was selling to.

I worked on him for two years and I finally got him to take underground comix. I was thrilled because I knew this was, boy, we're going to really sell a lot now because we're going to go all over and everywhere. Then I kept waiting for that first big order and that first big order and nothing happened.

What eventually had happened was that the attorney Albert Morris had become Crumb's best friend attorney. Unbeknownst to us, he'd gone and found an early catalog that Marty was putting together that showed the covers of all the comic books on it. He sued Marty for infringement, copyright infringement of using Robert Crumb's art that was on the cover of the comic.

It was just absolutely bonkers. How can you possibly sell something unless you show a picture of it? He was completely wrong, but poor Marty didn't know what was going on. The Feds were already trying to get him nailed for doing paraphernalia, that was the big deal. Anything that was associated with drugs was called paraphernalia and there were big laws against paraphernalia. A book of matches could be paraphernalia. You could still do hard time for having a book of matches on you if they decided to go after you in that direction. I didn't know it, but he was completely pissed at me for putting him through all that stuff, and he apparently paid a lot of money to Crumb's lawyer. I don't know how much Robert got out of it, but he completely made a big wipeout of our goals for distribution.

I want to move into the '80s. In that time, both of you started doing products that you wouldn't have considered strictly underground and appealed more to that person who might be interested in comics generally. Denis, you started publishing Will Eisner in that period. Can you talk a little bit about how that transition happened and how the comic stores played into that as creating a market for that kind of product?

Kitchen: Well, actually the first Spirit I did was I think in '72, so it was pretty early. We did two issues. We called them the Underground Spirit and they were successful enough that Jim Warren noticed it. He went to Will and he said, 'Look, this long‑haired guy in Wisconsin can sell 20,000 of your book." He said, "I can sell six figures ‘cause I've got newsstand distribution." He lured Will away and Will did say, "Oh, don't worry, Denis, we'll do more business together," and that did happen, but briefly, I was kind of the guinea pig for the larger market.

Generally speaking, obviously, the undergrounds, pure undergrounds, were my first love, but it was clear that there were other opportunities to do things that were maybe more appealing to the, let's just say the generic comics collector. Eventually, I did a superhero parody called Megaton Man. I think I did a High Adventure, which was like a Star*Reach adventure, Marvel with nipples, I think we called it. And eventually also merchandise. I always loved merch. We always had things like box candy bars and tins of candy and obviously 3D comics.

Turner: Your metal plates.

Kitchen: That's right, the tin signs. I always loved that stuff. It augmented what we were doing, and they weren't for every shop, but the shops who liked them would do very, very well with them, especially the candy as it turned out. We ended up doing, we had a license, we did Freak Brothers candy and Betty Boop and, of course, Crumb and a number of them.

Turner: Taken by the Devil Girl.

Kitchen: That's right. "It's bad for you." That was the tagline.

You got Spirit back at some point and I guess what I'm trying to get at is the transition of your customer base or the expansion of your customer base beyond that head shop group. Did that create the ability to publish this wider range of product than you had before?

Kitchen: It did for me. I think you probably have a better handle on the dates, but it seems like by the late '70s, the head shops were really in serious decline. A lot of local ordinances were trying to drive them out of neighborhoods and the ones who tried to survive would say, "Well, we sell tobacco products." If that was your defense, then if you had a rack of comics that had Dope Comix or Freak Brothers, you couldn't very well convince a judge you really were just selling tobacco products. They were literally dying and/or dropping comics for political reasons.

The Spirit had done very well for me. There was a big fan base for that. Then I started getting the license for other classic comics I love, like Li'l Abner and Milton Caniff, Alley Oop, go down the list. That was a comfortable transition for me because I love those strips and I wanted to grow that market.

At a certain point, the transition became virtually complete. Ron and Last Gasp and a few others would carry what undergrounds I had for that declining market. I was focusing principally on the larger Direct Market at that point as a practical matter.

That was selling to all the direct comic distributors that were also doing Marvel and DC?

Kitchen: Yup.

Click here for Part 3.

The Growth of Underground Comix Distribution

Posted by Milton Griepp on November 16, 2023 @ 4:20 am CT

MORE COMICS

'Venom' #252 to Feature Backup Story with New Suit, Plus New Story by DeFalco and Frenz

August 4, 2025

Venom #252 will feature a backup story about Venom’s new suit as well as a backup story by Tom DeFalco and Ron Frenz, the creators of the symbiote suit.

Showbiz Round-Up

August 4, 2025

The post-SDCC showbiz news is still spicy a week after the show's conclusion. It's time for another round-up!

MORE NEWS

New Anime-Style RPG by Two Little Mice

August 4, 2025

Free League Publishing announced Twilight Sword RPG , a new RPG by Two Little Mice.

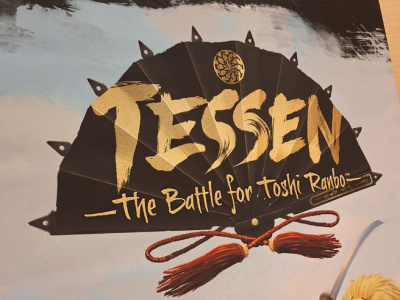

'Tessen: The Battle for Toshi Ranbo'

August 4, 2025

Office Dog previewed Tessen: The Battle for Toshi Ranbo , an Legend of the Five Rings board game.