Like many comics retailers, Chuck Rozanski got an early start, selling comics at an antiques fair when he was 14. Since then, he has grown his business to include both online sales and brick-and-mortar sales in his 45,000 square foot Mile High Comics store in Denver, Colorado. In Part 3, we discuss the current comics market, the importance of back issues, and why climate change is bad for comics. In Part 1 of this interview we talk to Rozanski about getting started in the business and rallying with other retailers to pressure Marvel Comics to change its trade terms and open up distribution. In Part 2, he talks about his own forays into distribution, mail-order sales, and online sales.

This interview was conducted as part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

To watch a video of this interview, see "ICv2 Video Interview – Chuck Rozanski, Part 3"

How did e‑commerce affect the Direct Market and the overall business of comics?

The way that it really affected things was for us, it blew up our business. There were periods in the early 1990s when if we took in less than $10,000 a day through the website, my wife, Nanette, who by then was out of the Alternate Realities business, would freak out because she'd be looking at our checkbook, and the bills we had to pay, and $10,000 just wasn't enough. God, $10,000 today would be way better [laughs] than we're doing. It blew things up a lot. The thing to bear in mind was that since we were there first, we got the lion's share of the people that were going online. As other competitors came along and MyComicShop came along, our business declined, but the overall business went up.

I was shocked. I went out to see eBay at one point out in California, and their collectibles area told me that comics were their number one area, and that the buying and selling of comics was like a nine‑figure business. I was like, "What? I had no idea." They said, "Yeah, our bestsellers are Dells." It's like, "What? What the hell are you talking about?"[laughter]

There were many, many revelations that came out in that time. The biggest thing that came out was that the overall market for comics is way broader than people think it is when they're sitting at the counter of a comic book shop. They don't understand that there are tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people that have an interest in comics that would never set their foot in a Direct Market store.

You mean they're buying on eBay or buying mail order?

There are so many different venues where people buy comics these days. They go to flea markets. They buy off of Craigslist. They buy off of Facebook postings, Facebook Marketplace. They buy everywhere that you can possibly imagine. And yes, eBay is still a big market.

The market for comics, and this goes in lockstep with the realization that almost all the comics from the last 40 years since I helped innovate changing things from Phil's system to this wide-open, wild west system of distribution, all those comics have gone into plastic bags because, by 1983, my prediction easily came true that we were 30% of the market, by 1985, we were 50% of the market, and by 1990, 90% of the market was going through the Direct Market comic shops. All those books were going into plastic bags. What exists as a tangible will transact. That's exactly what we've got out there right now.

New comics today are having to compete with their ancestors, with their prior brethren, who are out there offering an alternative in both quality and price to the new comics of today. That's why it shocks me not in the slightest that the new comics business right now is in the toilet and swirling around the bowl. Because there are so many better, cheaper alternatives, oftentimes of exactly the same ilk: comics, but at a much cheaper price.

That's a great observation because I don't think most people think about the fact that new comics aren't just competing with other new comics or other forms of entertainment, they're competing with every comic that's come out throughout history that's still available.

I ran the numbers one time, and I came up with the number of 2 billion. There are 2 billion comics that were printed during that 40‑year period.

OK. [laughs]

Think about the number 2 billion. That's a lot. That's six or eight comics for every person that's got a pulse in America. The one thing that goes against that, and this is a revelation that I had, that I had never gotten my head around, but now that I have, I'm very attuned to it, and that is that climate change is the greatest enemy of comic books. We are seeing more comics being destroyed these days because of catastrophic weather events than at any time in history.

Bill Schanes (you were talking about Bill earlier), on Facebook this morning, he put up a post about the little river that's next to his farmhouse or his daughter's farmhouse, and it was almost overflowing its banks and heading for his barn. Now that's just one instance, but there's this giant storm moving up the East Coast right now, and they're saying that localized flooding of 8 to 10 inches is expected. Comic books will die tonight.

Hold onto your armchair. Sit back and contemplate this. Every time you're watching the news, and you see a tornado, or a forest fire (Charles Schulz's entire collection burned up when the Paradise Fire happened), you see a fire, you see a flood, you see a tornado, comic books die every single night. The death rate right now exceeds the printing rate. That is a weird contemplation to get your head around, to realize that the number of back issues extant is actually now in decline for one of the first times in history.

It's very, very interesting when you start to think about it, but when you go backwards and you start thinking about what was really, really common and available in 1980: Big Little Books, pulp magazines, 1930s movie magazines. Nowadays, those have become way more collectible because they're just not as common as they used to be. Where did they go? The answer is a great many of them have been destroyed, and that is just so weird to think about.

How many people do you know, Milton, whose collections, they'll tell you, "My basement flooded," and they lost their entire collection?

Right.

I can reel off half a dozen, including people that worked for me, where they lost complete Silver Age DC because a pipe burst while they were working for me here at Mile High and they went home and found that they had a swimming pool for a basement. It's just so common that it's crazy‑making.

Then let’s talk about where we are now as far as the comics Direct Market. There are a couple of thousand comics stores across the United States, most, but not all of whom, carry some back issues. Some just carry new. Some are more focused on book‑format product. There's a pretty wide variety of styles of retail. What's your thoughts on where the Direct Market is now and where it's headed?

The Direct Market, if we look at it broadly, and we look at people who carry new comics and also other products, but new comics are a substantial part of their mix, those kinds of stores have tremendous possibilities because there's all kinds of changes in popular culture that are bringing people in.

I think that the model that became super popular starting in the late 1980s, early 1990s, we call them the brick sellers, where you've got a hole‑in‑the‑wall shop somewhere with your windows plastered with posters so that nobody can look in, so you create this cloistered little environment for the fanboys. Then they come in once a week and you hand them their brick of comics that they preordered and they walk out the door. Those kinds of stores are zombies. They're dead and they don't even realize it yet. They might be still shuffling around and thrashing a bit, but they're dead because that model is over.

The stores that are diversified, and that are in either one or two [models]. You’ve either got to have a super high traffic location where you're on top of it, and you know exactly what the most recent popular culture trends are, or you've got to be in a destination‑only location, which is the model that we've taken, where I bought a gigantic building where I can carry everything under the sun.

I'm in a place that no one would ever believe that a retail store could succeed, and yet I've proven that it can be done. That requires a lot of use of Facebook advertising, a lot of use of just the Internet in general. We do many, many mailings a week. We do targeted mailings. We make sure that we drive traffic to this very isolated spot. It takes a lot of work and I'm not sure that's a model that works for everyone.

You also have to have a team of people that have expertise in a variety of product areas. That's much harder for a single owner‑operator. The model of having a larger space and a very diversified product line, I think that still has great potential. I think that comics can be an excellent core product. I just don't think that they can carry a store anymore.

What about comics content? That obviously changed a lot during the growth of the Direct Market because it could reach a different kind of consumer than was the case before comic stores existed. What do you think about how that content has evolved through the history of the Direct Market, and where that content is now, and where it might be going?

We have to differentiate here because, to me, comics content includes original graphic novels and periodicals. Periodicals have been relatively more rigid. You don't see much in the way of successful periodicals that are not superhero‑themed.

That having been said, we're seeing more periodical comics that appeal to broader audiences that are inclusive and include LGBTQ themes, or that are written by women for women. Those are helping a lot, but your traditional superhero comics tend to be rigid.

On the graphic novel front though, we're doing extremely well with young adult graphic novels. We have a really large selection here. We try to keep all the Graphix and all the Scholastic‑type material in stock. Then we also do really well with the biographic type graphic novels, original graphic novels, like March, or They Called Us Enemy, and things like that. These do really well for us, and they appeal to a totally different audience than periodical comics. Honestly, in our Jason Street Mega Store, it's less than 20% and it may be just barely over 10% of our weekly revenues comes from new comics. That is entirely or almost entirely by subscription.

We order less than a long box a week for the racks. If those haven't sold by three weeks out, somebody's getting an ass chewing because we do not want to lose the money that you're losing today on new comics if you don't have 100% sell‑through.

This is something that no one seems to grasp. It's just the hardest thing for retailers to seem to understand that. In 1974, when I opened up the first retail store, new comics were 25 cents. I was paying Emil 15 cents. If it didn't sell a month after, I sold it for 50 cents as a back issue; if it didn't sell within six months, I raised it to a dollar. I could do that with every single comic book. Thus, if I didn't have 100% sell‑through, I was cushioned from that because I could command a premium price of multiples above my original cost.

Today, that margin analysis has gone in inverse. People don't seem to get it that they're paying two and a half bucks for a goddamn comic book that the minute that it doesn't sell (which basically is a 10‑day sell‑through), if it doesn't sell in 10 days, it's worth a buck. If it doesn't sell in 30 days, it's worth 50 cents. You have a diminishment now in value rather than a gain. Understanding that over the 40 years of evolution of the Direct Market, that that economic model has completely flipped, that is the single most important thing people need to understand. So many of them don't.

When I go into a comic shop and I want to see if they have a chance of surviving, the first thing I do is I look at the depth on their new comic rack. If they have more than five copies of a book from three weeks ago, they're already dead. They just don't understand.

What they're doing is they're taking on all the risk for their maybe customers. They maybe, might come in, but you're 100% invested in that book. If they don't come in, you're screwed. Why in the hell are you catering to the maybe people? It's moronic. It's just the dumbest thing you can possibly do.

You talked about a little bit in terms of where your business is now. Talk a little bit about this store, which I think we've run pictures of on the site because it's so amazing. It's so huge. You have so many comics. That and your e‑commerce business, how do those fit together? What's your business like today?

Our business is about 50% through the store now and about 50% e‑commerce. I have to say that I could be doing vastly more in e‑commerce if I wanted to because I have my prices set very high.

I do that on purpose because I actually look at the cost of replacement, the cost of the labor inputs, the cost of the supplies, the cost of the advertising to sell things. I fully allocate the costs and that precludes me from giving comics away.

I see other people that are doing it. I use the word “flippers.” They'll buy a collection and they don't really give a rat's ass because they're not stocking them. I stock. That database that I started with back in the mid‑90s is today immense. We have so many different comics and so many different variants in there, and I try to stock them all, and there's a cost that's associated with that. If I ever decide (which I may, because I'm starting to get a little long in the tooth), if I ever decide that, "Well, OK, it's time to start winnowing down a little bit," I have 10 or 15 million comics that I could put out there in the marketplace real cheap if I wanted to. Absolutely everyone out there should kiss my ring for every day that I don't do that. Just saying. [laughs] Here in the store, back issues and new comics are about 35%, 40% of our business, and graphic novels and trades are about another 30%, and then the remaining 30% is pop culture, which includes things like manga and anime, toys, and ephemera. By having a really broad mix like that, we bring in all sorts of different fan groups. We try to stock everything from My Little Pony to Simpsons to Aliens to Game of Thrones.

The thing that people are missing is that every single person in America has some sort of pop culture crap in their house, and every single person in America eventually dies, a lot of times they move, and amazingly, often they get divorced, and they got nowhere to put this stuff, which is why there's so many storage units in America. Some people get tired of paying those storage costs. We've had people who have driven up to the front door of Jason Street, pitched their boxes out the door, and driven away. That's our implied cost of capital. Nothing. We get this stuff and we're able to sell it in amazing quantities and our margins are 90%.

Any final observations on this occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Direct Market?

I love the Direct Market and I use harsh language in describing the current state of affairs because that really is how I view things, but in my heart of hearts, I want it to continue and I want the people that I know and really like in the comics business to succeed. But the key to survival is flexibility.

I'm one of the few people in this business who has actually made a lot of money doing this. I own this building, which is valued at $10 million. I own everything in this building and I own a lot more stuff besides that. You may not like me. You may think that I'm an arrogant little POS, but I've been at this game 53 years. I won, bitch.

That's a great place to finish. Thanks so much.

On Back Issues and How Climate Change is Killing Comics

Posted by Milton Griepp on December 31, 2023 @ 2:16 pm CT

MORE COMICS

Hard-Boiled Thriller About a Sinister Utopia

August 5, 2025

The three title characters investigate the dark underside of a utopian project in this hard-boiled thriller.

Column by Rob Salkowitz

August 5, 2025

In this week's column by Rob Salkowitz, he looks at the industry's biggest show, held in the midst of some existential issues.

MORE NEWS

'Heroes of Faerun' and 'Adventures in Faerun'

August 5, 2025

Wizards of the Coast unveiled two Dungeons & Dragons: Forgotten Realms books.

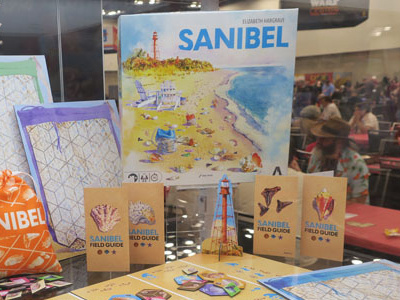

New Board Game by Elizabeth Hargrave

August 5, 2025

Avalon Hill showcased Sanibel at their booth, a new board game by Elizabeth Hargrave.