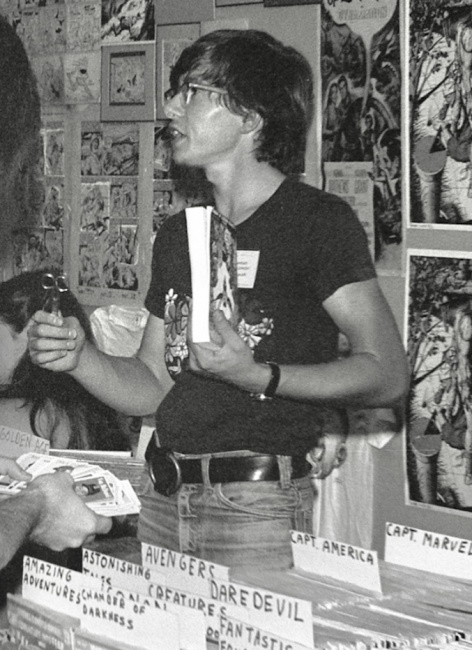

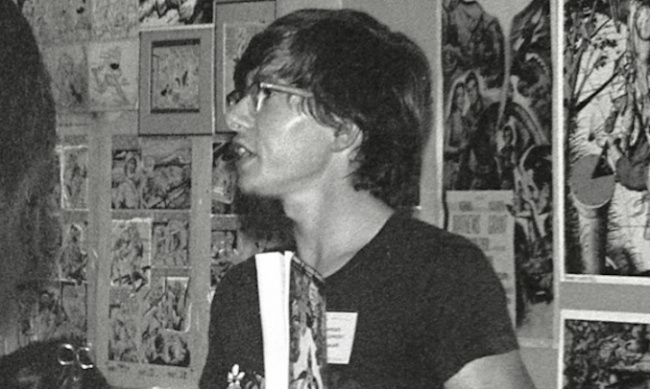

Like many comics retailers, Chuck Rozanski got an early start, selling comics at an antiques fair when he was 14. Since then, he has grown his business to include both online sales and brick-and-mortar sales in his 45,000 square foot Mile High Comics store in Denver, Colorado. In Part 1 of this interview, we talk to Rozanski about getting started in the business and rallying with other retailers to pressure Marvel to change its trade terms and open up distribution. In Part 2, he talks about his own forays into distribution, mail-order sales, and online sales. In Part 3, we discuss the current comics market, the importance of back issues, and why climate change is bad for comics.

This interview was conducted as part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary."

To watch a video of this interview, see "ICv2 Video Interview – Chuck Rozanski, Part 1."

It’s great to have with us Chuck Rozanski, one of the most well‑known comic retailers in the country, someone who's been involved with the direct market for many decades. Maybe we could start out by talking about the very beginning of your career in comics. What was your first experience buying and selling comics?

I first started selling with my friends in junior high in 1968, 1969. We were using, in those days, the old Robert Bell catalogs to buy and sell old Marvels. That was the beginning. I really got the bug by going through the Bell catalog, and the Rogofsky catalog, and the Grand Book, and the Passaic Book, and all those different catalogs. I sent away for all of them, and I started memorizing the prices.

When we left Germany, which is where I started (we were in American housing over in Germany), what made comics so popular there was that we had no American television. It was like transporting back into the 1940s all over again because comics were our number one form of entertainment.

You were living in Germany. Were you a service family?

My stepfather was a career army sergeant in the American housing in Frankfurt, Germany. We moved from there to Colorado Springs where my stepfather intended to retire. Almost in the very first month, I went to an antiques fair that was held in the Art Deco City Auditorium downtown.

That antiques fair was really kind of upscale. There were maybe 150 vendors in there, but there were people who sell coins and all kinds of early antiques. The people that I gravitated towards were the people that sold old toys, like old tin toys from the 1930s and 40s. Anyway, I was 14 years old at the time and I wanted to get involved there.

I met a kid there whose mom worked for a local ID wholesaler, and she had been for about 15 years, and she brought him home stacks of comics every week. He said, "Those comics are in the way in my room, and I really want to get rid of them." So I went to his house. It was really a challenge because it was a bitterly cold day in January of 1970. I convinced my mom to drive me over there, and we picked up what was 4,500 comics, and I used those comics as my starting stock to set up my first booth at the antiques fair. So I began selling to strangers professionally when I was 14. I did my first national show, which was Oklahoma City, in '72 when I was 17. I opened my first store when I was 19, and I had four stores and found the Edgar Church Collection when I was 21.

Talk about the Edgar Church collection (see “Heritage Auctions Last Mile High Comics”) because certainly, when I first heard about you, that was one of the first things I heard about Chuck Rozanski.

For sure. One of the things that distresses me is that after spending seven years of working up to that point, I hear so often, "Oh, my God. That's how you got started in the comics business." Well, no. That collection at the time that I found it was valued at about $200,000, and that was a huge amount of money back in 1977, but it was not the be‑all and end‑all of all transactions in my life. It helped a lot. We were able to market that collection fairly assiduously in a way that allowed us to maximize revenues based on 1976 and 1977 values. Oh, my goodness, compared to the numbers that those books eventually brought, we sold them for a pittance.

That money went into building up the Mile High Comics mail order business primarily. That became a really important part of our business. But actually, what made us take off was, in 1985, I purchased what I call the Mile High Two collection, which was 1.8 million comics that were in a warehouse on Long Island. Those were all pre‑1983, so Bronze Age and prior comics, and they were all newsstand returns, so the vast majority of them were in really high grade. We eventually generated about $10 million out of that collection. So compared to the Edgar Church collection, the Church collection pales in terms of dollar amount, but it's way sexier, so that's what everybody thinks about when they think about Mile High.

I got like five questions from those parts of the story. The first thing was all those catalogs that you were first seeing that showed comic prices, were you seeing ads in the back pages of comics? Is that where you were finding those catalogs?

Yeah, they were in the classifieds. Those first classified ads started appearing in '65, but I didn't see them until '67, '68.

You talked about opening your first store. Were you Mile High Comics from the very beginning? Was that the name?

We were the Mile High Comic Center from the beginning. Then someone else took that Comic Center name and opened up a store in Lincoln, Nebraska, so I decided to shorten it just to Mile High Comics.

When you opened your first store, how did you get comics? Did you sell new comics, or was it just back issues?

I was really blessed to have an ID wholesaler who was my mentor. I have no idea why, because in those days, I was really a flaming, long‑haired, radical pinko, out doing anti‑war demonstrations and those kinds of things, and he was a John Bircher. All over his wholesale offices, he had these signs up warning everybody about communists, and socialism, and all that crap.

The fact that Emil and I hit it off was so strange, but he would sit me down for hours in his office and explain to me why I needed to pay him. I started the first store with $800 that I earned by living in my car for 14 weeks while I traveled around to comic conventions. Shortly thereafter, Emil contributed more into my store than I did, by advancing me credit against new comics.

Here's the miracle, and it really was a miracle. Emil owned the three biggest newsstands in the Boulder area. They were the highest‑grossing comic book outlets. At the time that I went to him, I noticed that he was taking a week to put the new comics out. They'd come in on a Wednesday and he wouldn't put them out till the following Wednesday.

I said, "Emil, can I have them the day they come in?" He said, "Yeah." I said, "This is going to hurt your sales." He said, "I don't care about comics." He said, "You just take them."

So Emil set me up with new comics at 40% off, non‑returnable, but gave them to me a week ahead of any other outlet in the city of Boulder. They killed. It was like shooting fish in a barrel because I had them a week ahead of anybody.

What was the name of the ID?

Columbine Distributing. I drove by there the other day. I give Emil Clausen credit, totally, for not only funding me in the beginning, but also giving me that critical app, that strategic advantage that almost guaranteed that I couldn't fail.

What was your first store like? How many square feet? What kind of display did you have?

It was horrible. I was in a converted coal storage room that was in the basement of the Citizens National Bank building in Boulder, which had been built in the 1880s. It was an old brick building. In the back of our store was the chute where they used to have horse‑drawn wagons. They would pour the coal down so that they could heat the entire building. It was a five‑story building.

We had no lights in there. When I moved in, of the $800 that I had in starting capital, $400 had to go to just hanging some fluorescents in there because all I had when I got it was a single light bulb. It had an unsealed floor that was caked with coal dust. I had to pull two all‑nighters in a row to lay down the sealer, let it dry enough to where then I could put paint over it. On the day that we opened, the paint was still wet, but I managed to pull it off.

I made $100 on that first day. That was more money than I had seen. That was just a miracle. We had to move out of there though, within about 30 months. Downtown Boulder now has this beautiful pedestrian mall, but they decided to build it soon after I moved into that location.

By the way, you could not get into my store through a front entrance. We were in the basement. There was a store in front of us, a science fiction bookstore, and she subleased us that space for $95 a month. In order to get into our store, you had to go down a set of concrete steps, go into her store, walk through the entirety of her store, and we were essentially her back room. But for $95, it worked.

Emil gave me that critical app that made people come up all the way from Denver. People would drive in because they could get their comics a week early.

You talked about your mail order business. When did you start selling mail order? Why did you get into that part of the business, in addition to the store?

I had done mail order earlier. I started off selling to people like Bruce Hamilton and Phil Seuling and all those guys. I was selling them stuff mail order in the very early 1970s, 1970, '71, '72, but I was horrible at it. I was in junior high, moved up into high school. I was always way too busy to ever get around to shipping packages, and that's bad form when you're selling mail order. I was running ads in the Rocket's Blast [Comicollector, a fanzine] and they were pretty successful, but shipping stuff was just not me.

After I found the Edgar Church collection, one of my former employees had gone to work for Richard Alf out in San Diego. Richard heard about my finding the Church collection and knew that I had my four stores and that they were doing pretty well. He approached me and he said, "Look, I'll sell you my mail order business." He said, "It's very short on inventory. I have barely nothing, but I'm very long on great systems for making sure that things get fulfilled." I paid him 20 grand for his systems and maybe 20 boxes of comics. His systems turned out to be brilliant.

The biggest thing that he gave me, and this was Richard Alf's idea, I've gotta really push this, Richard Alf turned me on to the notion of actually advertising comic books in the comics. The yellow ads that I started running in 1980, those were the result of a test that Richard had done just before selling out to me. He ran a little classified where he listed just a couple dozen titles. He got so much response from that, that he realized that he was out of his depth, that it was a great idea but that he could never do it. I paid him 20 grand for his systems, but what I really got was that one idea. He said, "Chuck, I have never seen anything blow up so fast in my life."

When I ran that first double‑page spread in Marvel Comics in 1980, we took in $108,000 in 90 days. Richard Alf was so right, and I was so right to give him his 20 grand. [laughs]

Other people were just advertising their catalogs. His innovation was actually listing individual comics that he had for sale, right?

Right, and he did it in a classified ad as a test. It was a little bit bigger than a normal classified, but it only had about maybe two dozen comics listed in there. It just blew up on him. That's when he realized he had to get out because he was selling 15, 20, 30 copies of the same comic when he had 2 in stock. That was a disaster. It turned into a logistical nightmare.

I talked to Bill Schanes. He had a similar experience with starting selling through the mail. It's, "Wait. I only have one copy of this. What do I do now?" [laughs]

That became the nightmare. That's why I eventually stopped doing mail order and transitioned to online.

We'll get to that. What do you remember about the first time you heard about the Direct Market as a way to get new comics?

I had a competitor in Denver, John Caruso. John was from Boston. He was a street kid. He was a real hustler. He was also of Italian heritage. He ran into Phil Seuling. The two of them became bosom buddies. I first heard about Phil when I discovered that John was getting his new comics at darn near the same time that I was. Here he was, right by the state capitol in Denver, which is a very, very busy area. Suddenly, I had a real competitor on the horizon. It was all because of this guy in New York who was shipping to him.

I had been to Seuling's conventions. I knew of Phil that way, but I didn't start buying from him wholesale until John set up as a sub‑distributor. Phil was giving his sub‑distributors 50% off and free freight in those days. I contacted Phil and said, "Hey, I'm interested in this 50% off, free freight deal." I forget if it was Phil or Jonni [Levas] (I think it was Jonni) said, "Nope, we're already selling to somebody in Colorado. We don't want another sub‑distributor there." I said, "That could be really unfortunate, because you're actually not per se allowed to not sell to somebody just because they're in the same geographic region." I said, "I guess I could call Peter Rogers, who's the head of the local bar association, who's also my attorney. We could go that route if you want to." I got a call the next day that said, "Yeah, OK. You're in." Rather than getting into an actual conflict, I just used what the Federal Reserve uses on banks, which is what's called moral suasion. I just said, "Hey, this would really be a better idea for both of us if we just work this out instead of getting into a catfight."

The saddest moment, I had to go into Emil and say, "Emil, I can't buy from you anymore." That was sad.

What year was that?

I'm thinking here. I believe it was mid‑to‑late '78.

How did that change your business, if at all? Was it just a different source, no other impacts, or were there any other impacts on your business from buying from Seuling instead of your ID wholesaler?

Yeah. There was a major cash flow impact. Initially, I was shielded from it a little bit because I was generating external revenue from selling the Golden Age, the Church books. It started to dawn upon me, fairly quickly, that Phil had no accounting system. He had nothing. It was not rudimentary, it was non‑existent. You paid him with your order 60 days ahead. He then got 90 days billing. He was doing a spread of five months with your money if the books shipped on time. The problem is that a lot of them didn't. There was one X‑Men Annual that I remember with particular bitterness that took 11 months to ship. It was supposed to ship one year and it shipped the following. All of my money for that book was tied up, and in those days, we used to buy a fair amount of those comics. Phil would be sitting on our money that entire time.

What really got to me and what got me to finally contact Marvel in 1979 was I was getting ready to do my summer orders with Phil, ordering my books. In Colorado, we get a lot of tourist business, so I was anticipating this big spurt in business in July and I was ordering in April, and I realized I didn't have the money to pay for the books that I needed in July. I had no bank lines. I had no source of credit, and Phil was demanding my money up front. That's when I said, "No, no, no. This has got to stop. We can't do this."

I started contacting other retailers and seeing if they felt the same way. There was this guy that worked for Marvel as a—I don't think he was an assistant to Ed Shukin. I think he was just in their marketing department. His name was Robert Maiello. He had sent around some survey that was relatively unimportant, but it gave me a name of somebody to contact at Marvel, and so I addressed this letter to him and laid out 10 points that I thought that Marvel needed to do if they were going to stay in business.

They were fairly self‑evident points, but they were things that weren't being done at the time, like letting us know in advance what their projects were going to be, letting us know if there was an artist change, or if a major character was going to appear, but then also extending credit.

I didn't know it at the time, but this was a minefield for them. I found out when I went to New York, but they had had such bad experiences with Big Rapids, as you are aware. They had already been burned, and Shelly Feinberg and the crazies over at Cadence Industries [then Marvel’s parent company] were already breathing down their neck.

There was just this huge swirl of craziness going on. I managed to get over a hundred retailers to sign a petition saying, "Hey, you guys need to change your business model because this is not working, the way that Phil is running it."

They invited me to New York. They had me fly out there. I was so poor in those days that I flew out on a redeye, took the bus in to the Marvel offices, which were on Lexington in those days, and I had to put my suitcase under the receptionist’s desk so that I could go off and meet with [Marvel President Jim] Galton and [Vice President – Circulation Ed] Shukin and Jim Shooter. That's the day that I met Jim Shooter.

If that was after Big Rapids went down, that must have been early '80s sometime.

No, I think at that time it was like '79.

Rapids went down in early '80s. Maybe they were already behind in '79, but they were still doing business with Marvel, I think. John and I started Capital City in April of 1980, and that was as a result of Big Rapids going down earlier that year, which I think was like February of 1980 or something like that. That was the final nail in the coffin.

That may have been the timing on it then because I met with them in, I think it was the first week of June in 1980 rather than '79.

Yeah, that makes sense.

The petition was '79.

What was that fellow's name at Marvel?

It was Robert Maiello. I have it on the original paperwork. I can try and track it down for you. I do have the original petition with everybody who signed it. In those days, there were only about 400 comic retailers in the country. Everyone that I knew willingly signed it. I even had some of the publishers who I knew through the science fiction bookstore. I knew some of the people like Ian Ballantine and people like that. Lots of people were signing this saying this prepaid business model does not work.

This petition, I assume those were stores that you'd met at conventions?

Yeah, there were people that I knew from conventions, primarily. Again, I was doing conventions from coast to coast in those days. At that point, I was starting to slow down, but I had met lots and lots of people over the five or so years that I'd been doing major conventions.

What was Marvel's response?

It was a really weird set of meetings that were based upon some odd circumstances. As I said, they had just experienced a big loss, but they also had just lost a ton of money trying to do this weird ad campaign in the San Francisco area for the Pizzazz magazine. They had done TV ads, and that had cratered on them and not done well. There were just other circumstances that I was made aware of that really put Jim Galton's position at risk. He normally was not a guy who was very open to external suggestions, but I hit him at just the right time apparently.

Jim Shooter had some wonderful statistics to back me up that said that the Direct Market was like a golden nugget within the Marvel marketing programs because he had kept track of all of Seuling's orders and the orders that were going in those days. There was Big Rapids, but also Longhorn was distributing early on, Pacific was distributing early on, I'm trying to remember, I think there was one other person that was distributing early, but anyway, Jim was adding those numbers up, and he came up with the fact that, from nothing, the Direct Market had become 5% of Marvel's business with a couple of titles, most especially X‑Men, Claremont and Byrne’s X‑Men, being 10%. I'm not sure if that's 10% of the print runs or 10% of the net sales, but either way, I was able to point to Jim's statistics and say, "Look, I think you could triple this within two years if you opened up more distributors and got them to go out and get more people selling comics, but they've got to have margin. They've got to have the ability to do that." I was really pushing for the 60‑off model.

I don't know if there was anybody more surprised than I was when they actually said, "Yeah, OK. We'll do it." I was like, "What the...?"

Do what?

What I was pushing for was the opening up of trade terms. I was hoping that the trade terms would be such that even I could afford to get in on them. Initially, I believe, that the initial wholesale requirement was either 3,000 or 5,000 a month of Marvel product in total. That made it doable for me to set up what was initially then Mile High Distribution.

Click here for Part 2.

On Early Retailing and Rallying Retailers to Pressure Marvel on Distribution

Posted by Milton Griepp on December 31, 2023 @ 2:13 pm CT

MORE COMICS

Coming April 2026

July 28, 2025

DC Comics will release the Batman by Darwyn Cooke: The Absolute Edition in April 2026.

From Marvel Comics

July 28, 2025

Check out the Marvel Rivals Swimsuit variant covers, coming this September from Marvel Comics.

MORE NEWS

Plus: Frank Miller Does Wolverine/Batman Backup Story for 'Deadpool/Batman' #1

July 28, 2025

The Marvel/DC crossover Deadpool/Batman #1 will have a backup story by Frank Miller featuring Batman and Wolverine.

Bonus Showbiz Round Up

July 28, 2025

Hollywood news has made it into bonus rounds after SDCC. So, this week, there is a Bonus Showbiz Round-Up!