As a follow-on to our project on the 50th Anniversary of the Direct Market (see "Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary"), we interviewed former DC President and Publisher Jenette Kahn, who was hired as DC Publisher, the first woman in management at the company, at 28, and went on to remain at the company for 27 years, a period that transformed DC and the comics business. In Part 1, she talks about how her early career starting magazines led to being hired at DC, what it was like coming into a nearly all-male company, and the early days of nurturing the Direct Market. In Part 2, she talks about the battles to get creators more rights and compensation, Karen Berger and the British invasion, the Batman movie and licensing, Vertigo and Milestone, the move into books, and some final thoughts.

ICv2: We’re fascinated with how you ended up at DC Comics. Maybe you could start out by telling us how you went from a Harvard BA in art history to creating three new kids' magazines, which were the roles that you had before you went to DC.

Jenette Kahn: When I was an undergraduate, I had a boyfriend who was at the Harvard ed school. He was really interested in publishing. He loved the physical aspects of publishing, choosing the endpapers, choosing the typeface. He scoured for emerging young writers in the Cambridge area with the idea of publishing their books. He did publish several.

Because he was at the ed school and student teaching, he saw all of this amazing work that kids were doing, whether it was writing or poems or artwork. He had an idea of publishing books written and illustrated by kids for each other. He told me about it.

I knew absolutely nothing about business, but said, "I think that's really such a lovely idea, except, just because I like looking at creative books aged 10, doesn't mean I'm going to like Jenette Kahn's book aged nine. You're constantly spending more money to market, to promote. "If it were a magazine with built‑in features that people look forward to, but also surprises, every month, then I think it could be a more promising business."

He said, "Oh. Well, write a prospectus."

Again, I had no idea what one was. By now, I think I had graduated. I wrote up something, and because my own art style peaked at 10, I painted some kind of template of what the kids' artwork might look like in such a magazine.

Amazingly (I still don't know how it happened), we found two businessmen in Boston who loved the idea. They said they would help us, and they helped us get a $15,000 loan from the First National Bank of Boston. They introduced us to a printer in Lowell, Massachusetts, where Dale Brogan was the foreman, and he was an extraordinary man, who also fell in love with the idea of a magazine written and illustrated by kids for each other. Amazingly, he gave us credit. We started printing Kids, and I came down to New York and found a distributor.

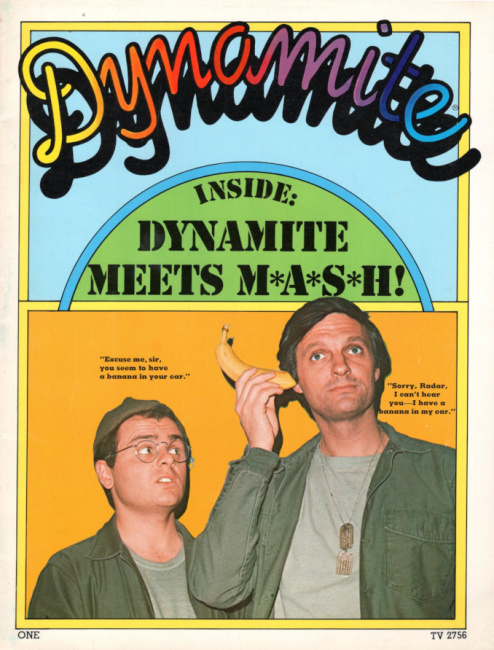

We got written up in the New York Times, and Life, and Look; we were on different talk shows. It was this extraordinary critical success, and an equally large financial disaster. By the time I was 23, I knew everything about Chapter 11 versus Chapter 10 bankruptcy plans. But I loved publishing, I loved telling stories, so I created a second magazine for Scholastic called Dynamite. It became the most successful magazine in all of Scholastic's history.

Although we had the agreement to agree, we could never agree because the head of Scholastic kept saying, "Well, you'd make more money than the Chairman of the Board if we gave you a royalty." I was like, "That's what happens in the record business. The executives are thrilled when their artists make more money than they do because it means that the records are really selling. Remember that." [laughs]

I didn't have a contract. I just had a letter of intent. I was a naïve 25‑year‑old. I called up Xerox and said, "I'm the creator of Dynamite. I want to work it out with Scholastic if I can, but we're rather far apart now. Knowing that you're still interested in talking to me, I would talk to you and make it worth sending a car."

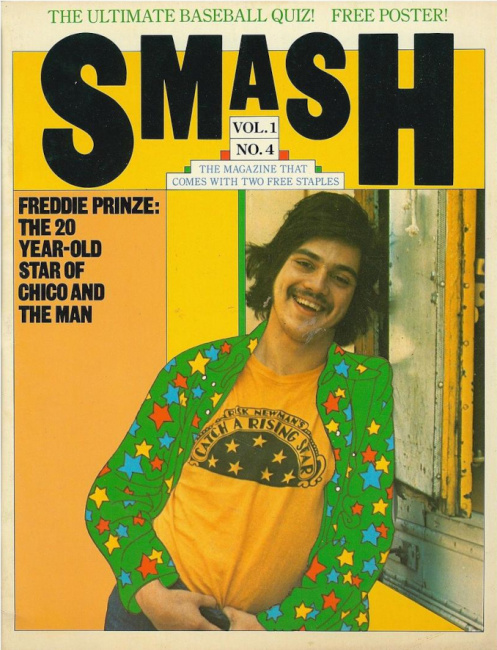

Ultimately, I couldn't make it work with Scholastic and created a third magazine, with Xerox this time, called SMASH, because I wanted to smash Dynamite.

It was while I was doing SMASH that what is now Warner Discovery called me up and said, "We're firing our [DC] publisher. We don't want to hire anybody. But you're now the expert at publishing for young people. Would you come talk to us?" Because of course, back then, comics were for young people. They were for kids.

I came and talked. Hopefully, I was polite. I was very forthright, very direct, because they were not offering me a job and I didn't want a job. The next day, the Chairman of Warner Publishing called me up. He said, "Want to have lunch?" I thought, "Lunch? Why is he asking me to lunch unless he’s going to offer me this job that does not exist." I thought, "Do I want it?" I thought, "I love making magazines. I love having a vision and making it tangible, but this was 80 comics a month. There was merchandise, television, movies." It was so over my head that I had to say yes."

On Groundhog's Day, February 2nd of 1976, I always say that I saw my shadow and stayed forever.

You were super young to be an executive at a publishing company and probably the first woman in management at DC Comics. Was it your track record that impressed them? Why do you think that you were hired? You were so out of the norm for who they had in management in the past.

I think I was hired for a confluence of reasons. First and foremost, I think it was that there was a seismic shift in attitude toward women and employment. What was then Warner Communications had, perhaps a year before, made a million dollar investment in Ms. Magazine.

Bill Sarnoff, who was the chairman of Warner Publishing, said that Gloria Steinem had raised his consciousness, and I really do think that that opened the door for him even to consider me.

Another reason was Bill had said that the men that they had interviewed were more interested in the big logo on the floor or the title on the door than actually the medium, and there was no doubt that I had a passion for comics, that I loved the medium.

Also, it goes back, I think (in connection with my art history degree), to the fact that I saw comics as an art form and as a distinctly American art form. I had literally a love of comics and a real respect for them.

Part of it was that there were men who weren't that interested in the medium, thinking that it was beneath them. "Really, comics? They are a disposable kids' medium," and the fact that Gloria Steinem and other women like Gloria had campaigned for more equitable awareness of women's capabilities.

I'm standing on many, many shoulders there, and the fact that there probably weren't that many people left, at least on the male spectrum, to hire for this job.

There was an opening to say, "Maybe it could be a woman after all. Here's a woman who loves comics and thinks they're an art form and wants them to grow and wants to elevate them. Maybe there's something there."

We interviewed Paul Levitz (see "Interview with Paul Levitz, Part 1"), and he described your arrival at DC as, "like a Martian landing."

[laughter]

What was it like to you coming into this basically all‑male company?

When I came to DC, it was almost entirely men. There was one secretary, there was one woman in production. When I needed to get some time to myself, I'd just go to the ladies' room, there was nobody there.

It was rocky at first because the men on staff in particular were not the least bit happy that I'd been hired. There was the sense of, "She's from outside the industry, she's a woman and she's younger than we are." It all just seemed so unjust, so unfair. It took, I should say, probably at least a year for people to think that I was actually there for the long run, that I believed in the medium, that I believed in the creators most especially, and that I wasn't looking at this as a stepping stone to something else. I was there because I was committed to the people and committed to the medium.

Sol Harrison was there, and you had to work with him, you both had executive roles. What was it like working with him?

Sol Harrison and I had a very uneasy relationship. I was going to be brought in as president and Sol, before I got there, made a play saying that wasn't right, he'd been at the company forever, he deserved to be president; and so I was given the title of publisher instead. I wanted to see us as partners, but I think Sol saw me as usurper.

So he stuck with his bailiwick, looking at the covers, coming out of production. "That’s an interesting cover, will that deliver sales from the newsstand?" I tried to focus on the content of the comics and building relationships with artists and writers.

It was five years of not overt friction, but I'd say of subtle unease, and then Sol opted to retire, and that really was a pivotal point. It gave me the chance to spread my wings in terms of the company and spread the wings of the company, even more importantly, not just my own, but what the company could be and could do when there was no longer this quiet competition between Sol and me.

When you got there, what role was the Direct Market or the comic stores playing in decision‑making at the company? Was that a factor in how you were making comics at that point, or was it too early?

When I got to DC, the Direct Market was just in its infant stage, so we were not focused on the Direct Market at that time. We were aware of it, but not putting our money, or our time, really, to any degree, into it.

I know that Sol would work with Phil Seuling, and make some private deals. It wasn't until Sol left that the area of sales really fell under me (which had been Sol's field prior to his departure), and my partner in crime, Paul [Levitz], and I could really talk about the Direct Market. What does that mean for comics? What is the future of comics? What is the future of sales? I have to give, of course, a huge shout‑out to Phil Seuling in this. We would not have a Direct Market, I don't think, without Phil and his vision.

My other enormous shout out is to Paul, who was the best of partners and my ally in everything that we did in DC. We looked at the markets where we were putting four comics on a newsstand and selling 25 percent of that, one comic for every four.

Instead of getting real returns, getting the comics back and maybe recycling them in some way, we would just get one third of the cover back to say, "Oh, well. They hadn't been sold." Some kind of proof of that the wholesalers and the news dealers were not scamming us.

It was just a terrible, terrible business of returns and diminishing returns, and the Direct Market held the promise of many things. It held the promise of printing to order, of no returns, of financial stability. It also held the promise of a different audience, of a sophisticated audience, of an older audience that wanted more sophisticated content, which, of course, was an incredibly enticing possibility.

The problem for us with the Direct Market is that these were mom and pop stores, or they were pop stores. They were people who loved comics and didn't want to give them up, and wanted to deal in comics, wanted to read comics, wanted to share comics.

They were held together with business baling wire. They were all founded on shoestrings. The question was, how could they grow when they were so under‑financed, and we needed them to grow. Of course, they wanted to grow. If we extended too much credit to help them grow, then if they went under, they could severely hurt us, as well.

We brought in consultant named Leon Knize. Again, all props to Paul. They worked tirelessly together figuring out a credit plan that would enable us extend credit, help these comic book stores grow, and at the same time, not put us in too much jeopardy if they were to fail for any reason.

Of course, today we can see that that was a very successful plan. We all benefited from it, and benefited from it in terms of financial stability, in terms of the environment, because we weren’t wasting so much paper and so many comics.

It was so much better for artists and writers who now had a platform where they could really express themselves and write what they felt were stories that were personal for them and engaging for our readers. It gave us a chance to experiment on all kinds of different covers and different ways of marketing. It was a boon to the entire industry.

We could see the growth in baby steps. Bit by bit, it really became the norm for comic book publishing.

As the comic stores grew, how did that change the kind of material that you could publish or that was successful?

When comics are on newsstands, you have to be very careful in terms of content, because they're perceived to be for kids. Kids at a spinner rack will happily pick up a Superman comic, or a mother will pick it up for her daughter, thinking that the content is, of course, kid‑friendly, but it may not be.

We certainly wanted to make sure that we protect the audience. The audience for newsstand comics is either a parent or a young person, but the audience for comics at comic book stores, that's a sophisticated reader.

When we would do our analyses of who, it would almost always be a male reader, in his 20s, college degree, an early adopter of all new technologies. These readers, of course, craved sophisticated material. This enabled us to start lines like Vertigo, where artists and writers were given tremendous range in terms of the kind of stories they could tell.

Of course, this went hand in hand with the rights for artists and writers. I don't think we would have gotten the amazing stories that we did, the Watchmen, the V for Vendettas, the Preachers, the Fables, all the extraordinary comics that came out both because of the Direct Market, but because of our change in rights for artists and writers.

Up until Vertigo, the target market was, at least from our perspective in distribution and the comic stores that we were selling to, overwhelmingly male. Paul talked a little bit in his interview about how, on the newsstand, there were some comics that were selling to girls, like the horror comics, but as the decision was made to shift to the Direct Market, most of those were canceled. What were your thoughts, at the time, on the gender of your customers and who you were appealing to? What about that girls market?

Most of our readers who are going to the comic book stores on Wednesday to get their fix, we knew that they were almost entirely male. What we were always thinking was, what are the best stories we can tell?

Ultimately, the best stories began to attract women readers as well as men. We have something like Sandman. I don't know what the actual numbers are, but I would imagine half of the Sandman fans are women. Good stories should be able to attract readers regardless of gender.

When I came to DC, we were publishing a huge amount of male fantasy publishing: the men that readers hoped to be and the women that they wanted to be with. Once we started publishing for the Direct Market, just telling what we thought were good stories, then that began to open up the readership.

Of course, as we brought on women editors, people like Karen Berger, like Shelly Bond, they also brought in women writers and artists, and expanded the universe on the creative side and on the readership side.

Click here for Part 2.

Getting Hired as Publisher at 28, the First Woman in Management, the Early Days

Posted by Milton Griepp on February 9, 2024 @ 4:24 am CT

MORE COMICS

A Trip Down the Witches' Road Reveals Secrets About His Legacy

August 21, 2025

To save his husband, Hulkling, Wiccan takes a journey down the Witches’ Road and learns more about his powers.

From DC Comics

August 21, 2025

DC Comics has unveiled more details surrounding comic book event DC K.O. #1, launching on October 8, 2025, including a "Lights Out" polybagged foil variant program.

MORE NEWS

For 'Warmachine' Miniatures Game

August 21, 2025

Steamforged Games unleashed Cryx Hellraker Colossal Miniature , a new miniature for Warmachine miniatures games, onto preorder.

New Board Game by Level 99 Games

August 21, 2025

Level 99 Games will release Spooktacular , a new board game, into retail soon.